2022 report

Change & Emergence

in Latin America

Value flow

Current Situation

A snapshot of key facts and indicators

Policy response capacity, economies in Latin America have less favorable financing conditions and fewer resources to maintain monetary-financial stability for the current and coming crisis.

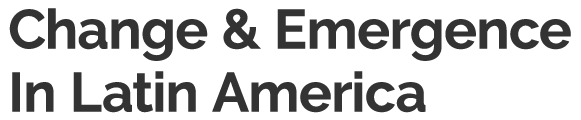

Figure 1.1 shows how advanced economies are able to maintain low interest rates, even negative in some cases.

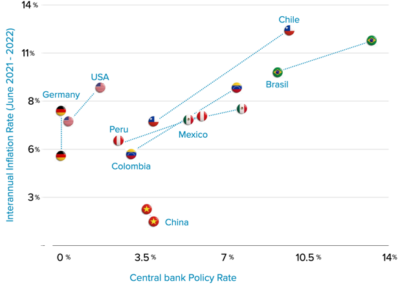

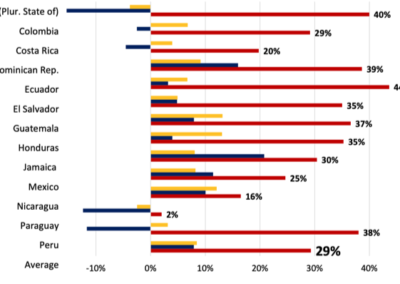

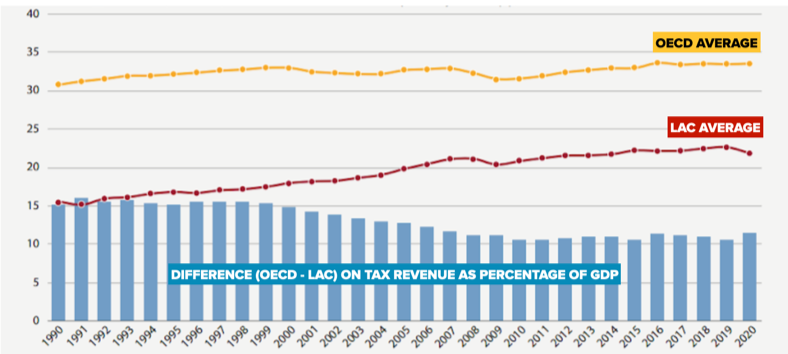

Reduced space for fiscal maneuvering, low tax revenue (figure 1.2) and an uncertain financial context adds up to the inflationary pressures and exchange rate volatility. Central banks mainly use interest rate hikes to deal with inflationary pressures.

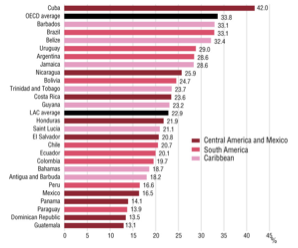

Low investment and productivity, slow recovery in employment (figure 1.3) and persistence of the social effects caused by the crisis.

The primary drivers of growth in 2021 were consumption and exports, private consumption increased with higher remittances flows (figure 1.4). Recovery in the United States bolstered exports, especially of manufactured goods and recovery in China impacted commodities prices.

Sources: 1.1 countryeconomy.com and global-rates.com 1.2 Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2021, report by OECD 1.3. Preliminary overview of the economies of Latin America and the Caribbean 2021, report by ECLAC. PDF 1.4 idem.

Current Situation

Selected problems snapshot

Introduction

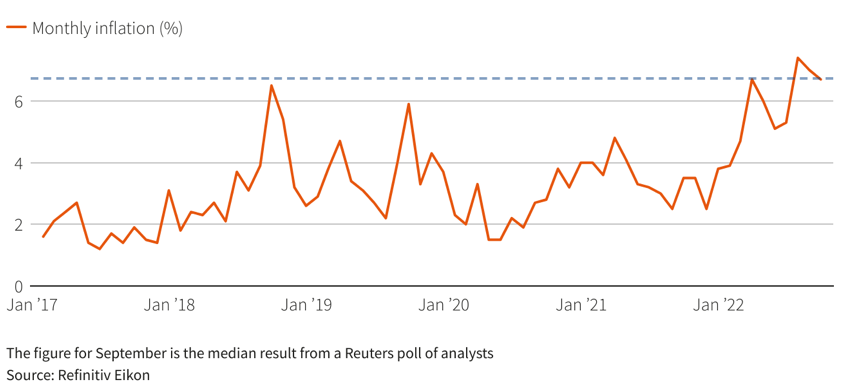

Argentina has long struggled to rein in fast-rising prices with inflation currently running at an annual rate near 80%. The government has pushed retailers to freeze some prices, with some supermarkets rationing purchases of staples like flour, sugar and milk but shopping costs have nonetheless soared.

Current Situation

Selected problems snapshot

The economic crisis of Argentina & Venezuela

Tax revenue

Argentina has long struggled to rein in fast-rising prices with inflation currently running at an annual rate near 80%. The government has pushed retailers to freeze some prices, with some supermarkets rationing purchases of staples like flour, sugar and milk but shopping costs have nonetheless soared.

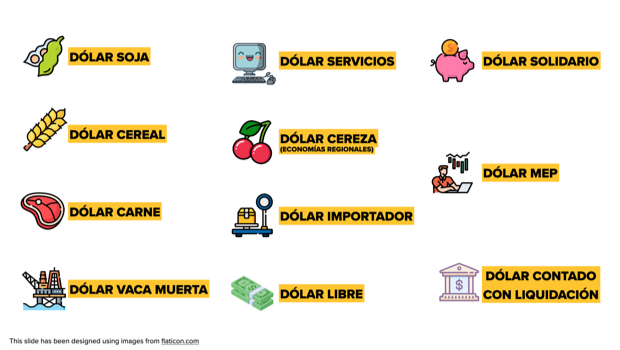

To control prices, dollar reserves and in general to delay a greater devaluation Argentina has multiple exchange rates. The rate depends on what you are buying; how good or bad it is that rate depends on what the government wants to curb or incentivize. As of October 2022 it has fourteen different rates, the most recent ones were nicknamed “Dollar Qatar” and “Dollar Coldplay”, aimed respectively to the tourism money getting out the country and to pay foreign entertainers.

Sources and references: “Todos los dólares: “solidario”, libre, bolsa, carne, cereza y otras alternativas en el país de los múltiples tipos de cambio” Infobae news report. “Argentina’s perpetual crisis” El Pais news report. “Coldplay and Qatar dollars: Argentina devalues its currency by sectors” El Pais news report.

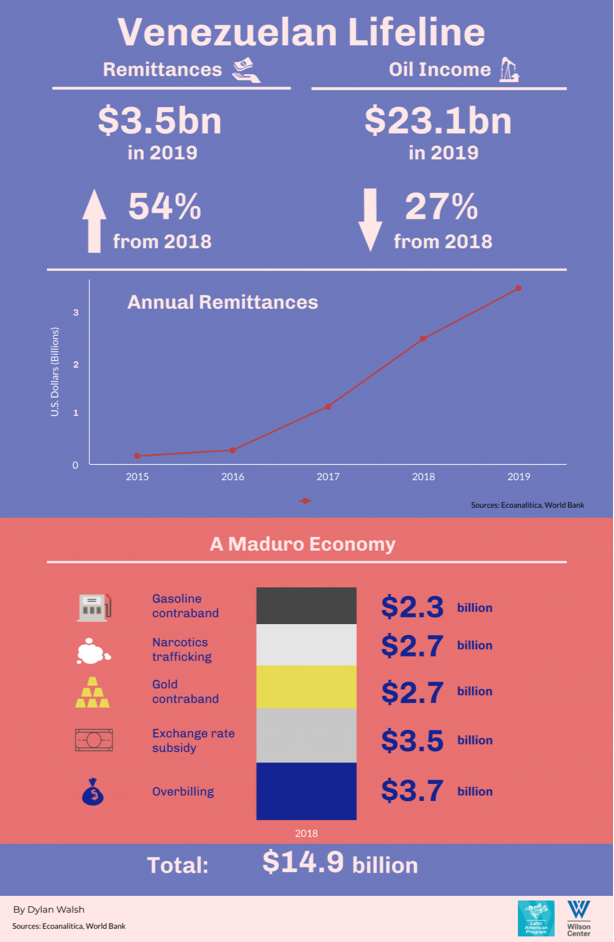

Venezuela is experiencing a de facto dollarization of its economy. The adoption of the US currency helped curb hyperinflation, but it’s now creating new problems. Bolivares are still being used and salaries are still paid in the national currencies although it is so devalued that in cash it is mostly used for candy or public transportation. The maximum that can be withdrawn from banks is 30 Bolivares per day, about $5 USD.

Dollars enter the country mainly through tourism and remittances. Still the population demands that salaries increase at the same rate of food prices is fueling strikes and protests.

Despite the macroeconomic upsides to remittances and dollarization, Venezuelans continue to leave in large numbers, ballooning the flows of dollars into their isolated homeland.

Sources and references: “Venezuela curbs hyperinflation” DW news report. “Amid Venezuela’s Exodus, Remittances Boom” WIlson Center blog post by Beatriz García Nice and infographic by Dylan Walsh with data from econoanlítica from World Bank

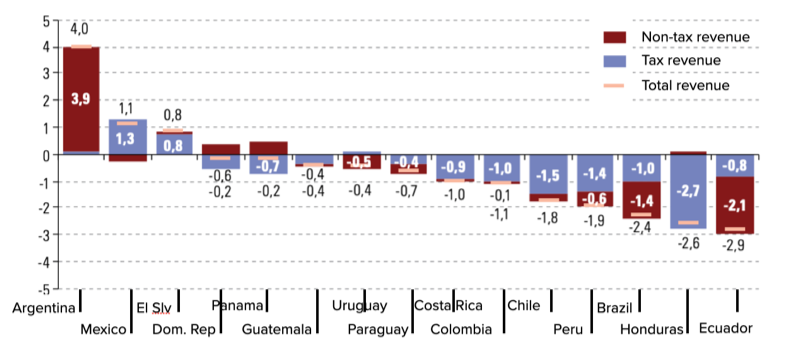

It is important to note that the reduction in tax revenues in 2020, although significant in magnitude, was less than that observed during the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008-2009 in several countries in the region. In this sense, the cases of Chile and Peru stand out, where the smaller drop is mainly explained by the performance of mining tax revenues. In Chile, for example, mining tax revenues fell from 3.5% of GDP in 2008 to 1.5% of GDP in 2009 (2.0 percentage points), and from 1.0% of GDP to 0.7% of GDP in 2020 (0.3 percentage points). A similar situation is observed in Peru, where tax revenue from the same source fell from 1.9% of GDP in 2008 to 0.8% of GDP in 2009 (1.1 percentage points), but remained stable at 0 .4% of GDP between 2019 and 2020. It should be noted that, while in 2009 the international prices of minerals and metals had fallen sharply, in 2020 there was an increase in the prices of several products, including copper, despite the strong contraction that had taken place in the first half of the year.

Although in most countries there was a significant reduction in such income, in others, the tax burden rose during the year. In this sense, the cases of El Salvador and Mexico stand out. In El Salvador, although tax revenues fell in real terms, the fall was mitigated thanks to the increase in income tax collection from legal entities as a result of the tax amnesty implemented during 2020. In Mexico, for its part, tax collection increased in relative terms (1.3 percentage points of GDP) and absolute terms (0.8% in real terms).

Sources and references: Tax Statistics on Latin America and the Caribbean 2022 by OECD/ECLAD/BID (2022) https://oe.cd/RevStatsLAC. 1.6 Taxes in Latin America: Do Wealth and Inequality Matter? by B. Catelleti. Research Paper

Panorama Fiscal de América Latina y el Caribe: los desafíos de la política fiscal en la recuperación transformadora pos-COVID-19 pp20. PDF

A. Tax revenue average Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and OECD percentage of GDP

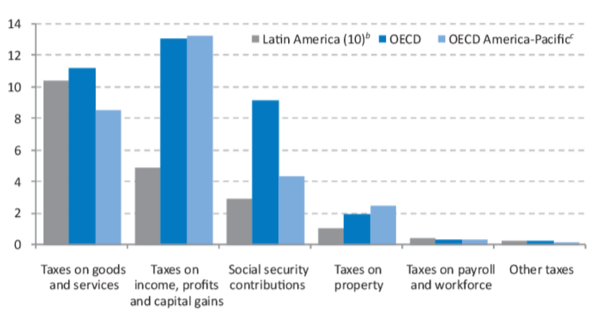

B. Tax revenue Sources

C. Variation in central government revenue, by component.

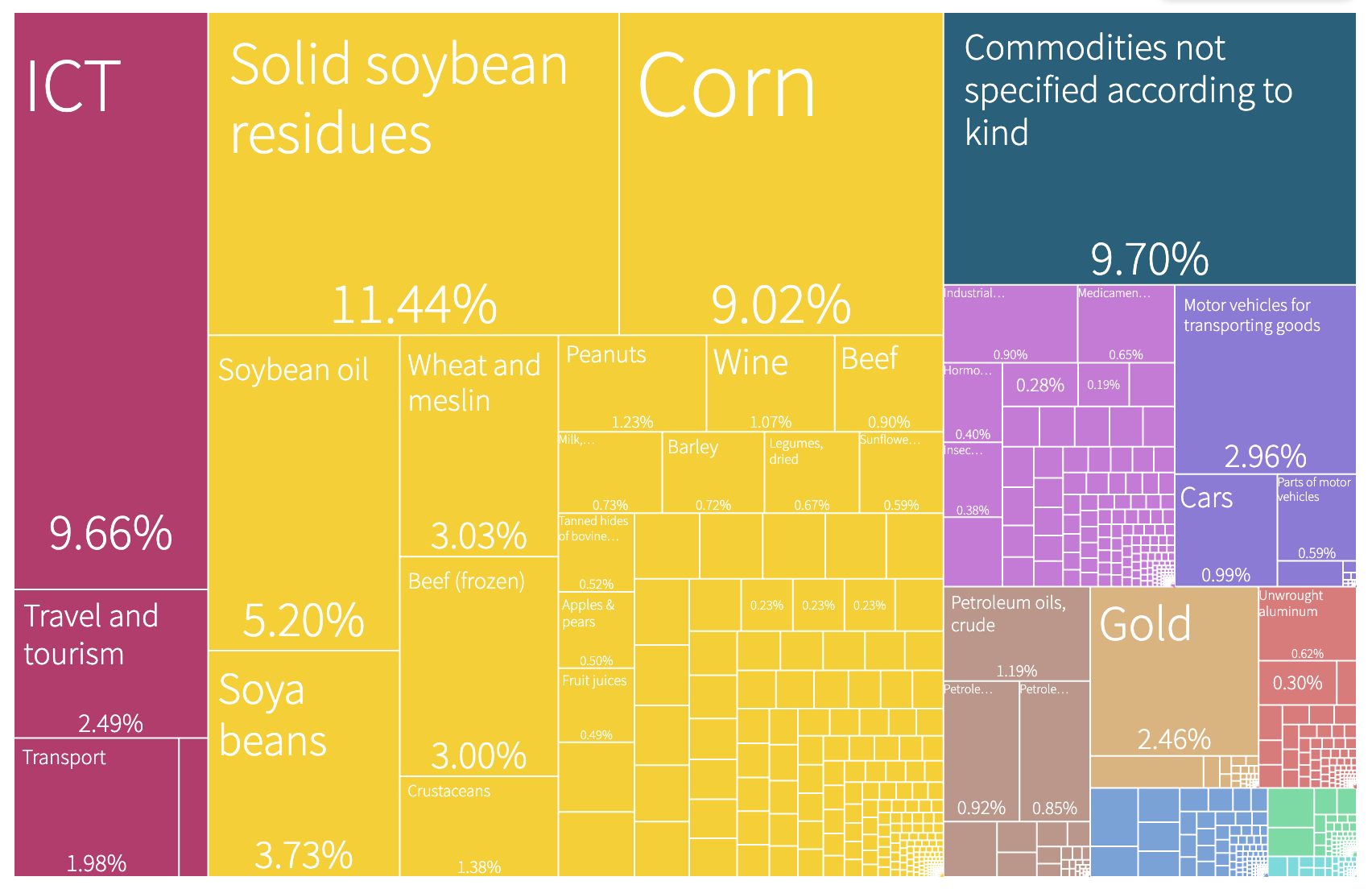

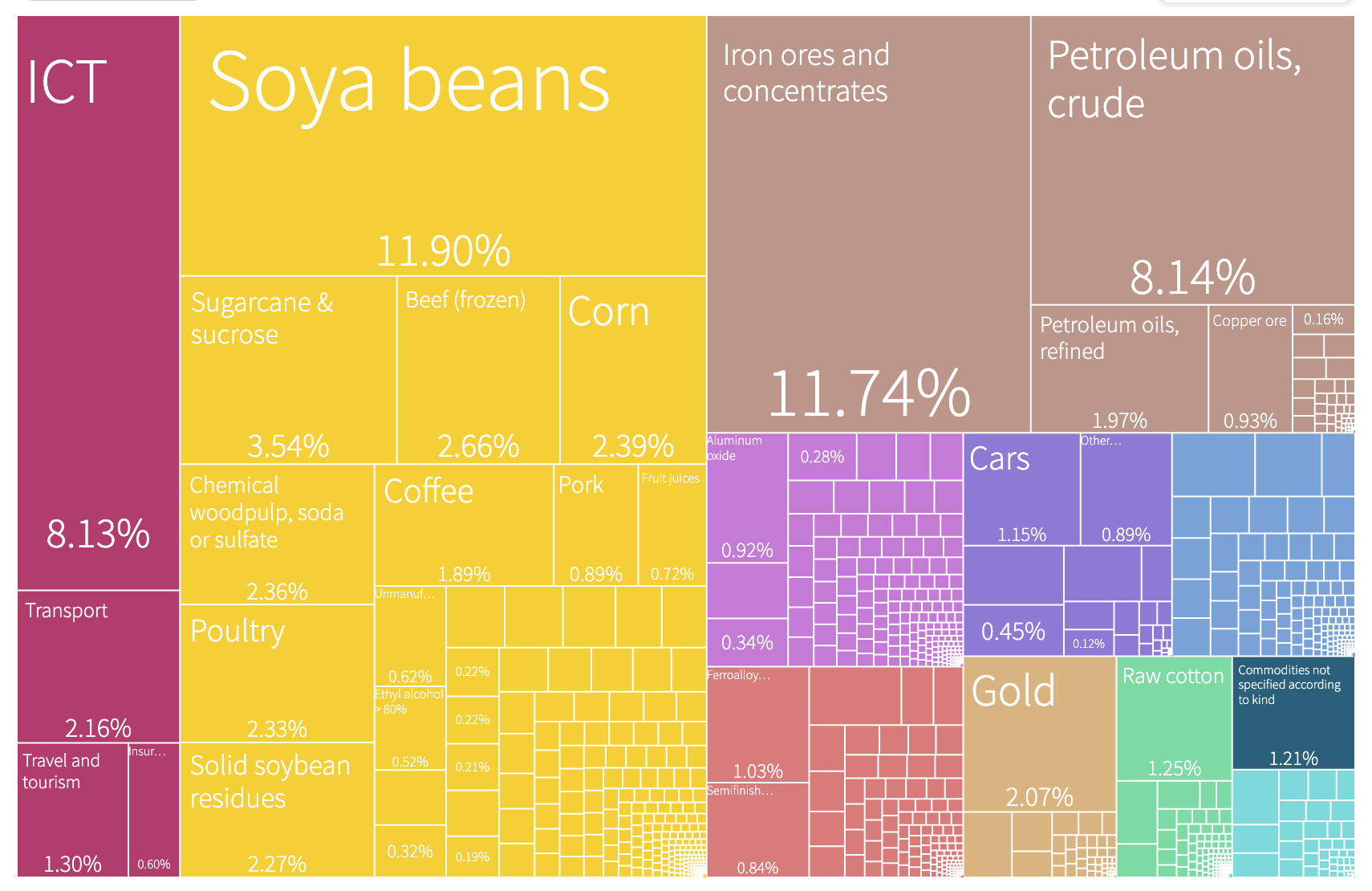

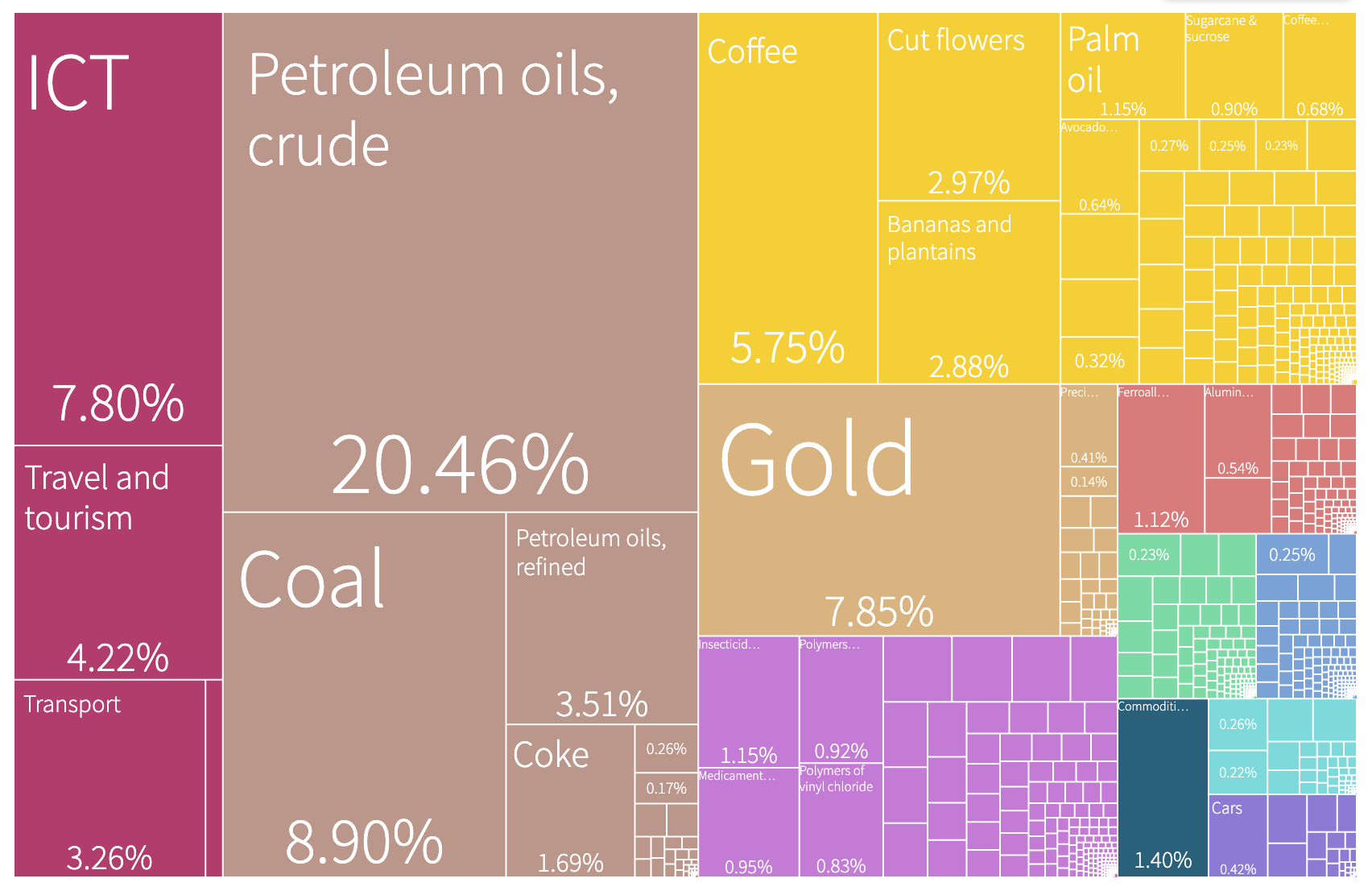

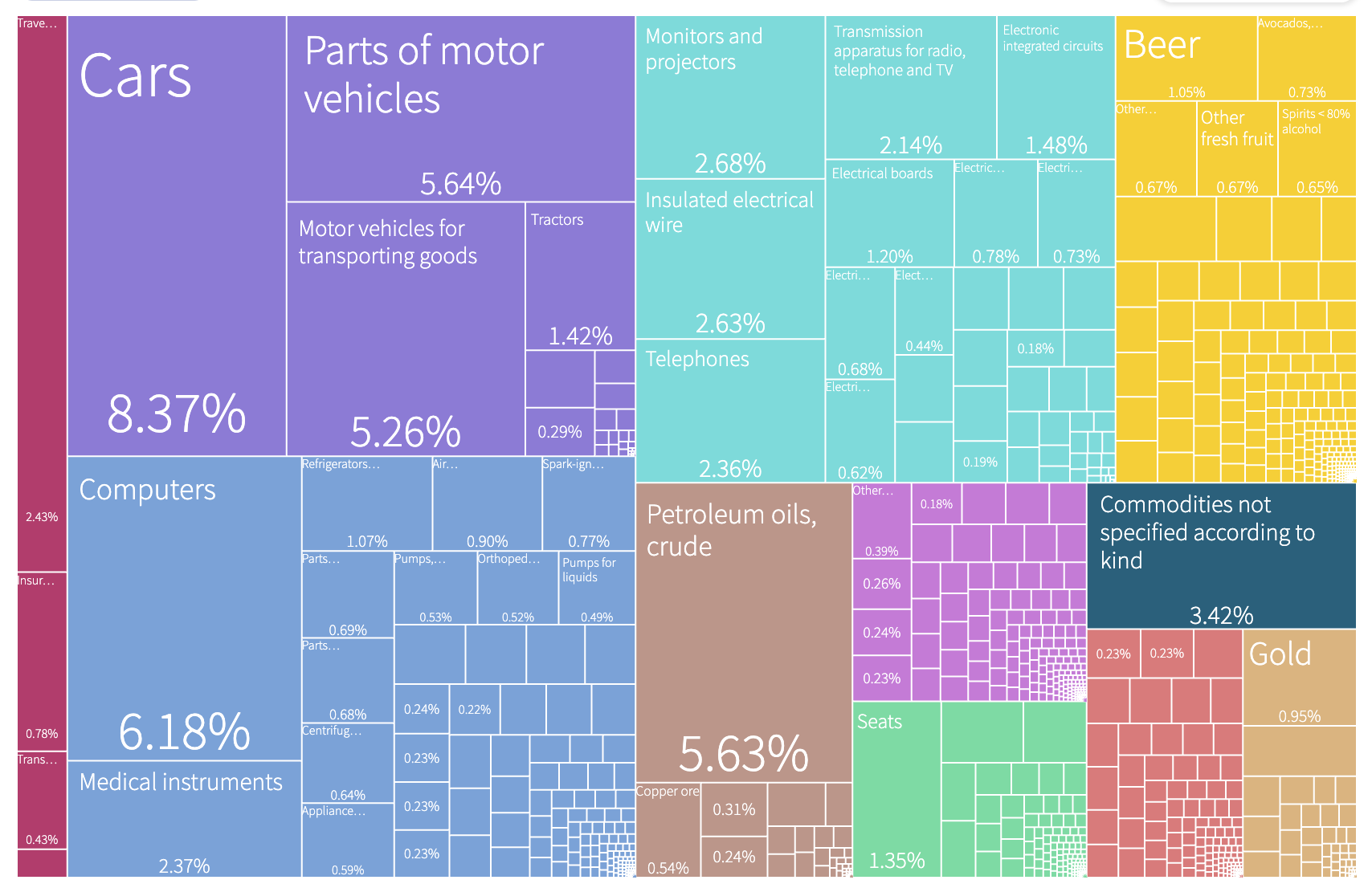

Top exports

Export Baskets in 2020

(Selected countries)

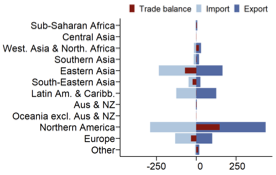

In 2020, the value of merchandise exports of Latin America and the Caribbean decreased by 9.4 percent to reach 925.1 bln US$ and its imports reached 869.8 bln US$ which was a decrease by 17.2 percent. The merchandise trade balance recorded a surplus of 55.3 bln US$ in 2020 as compared to a deficit of 28.7 bln US$ in 2019. Latin America and the Caribbean’s intra-regional total trade amounted to 250.1 bln US$, that is 13.5 percent of total exports and 14.4 percent of total imports. With regard to SDG regions, merchandise main exports destinations were Northern America (47.0 percent of total exports), Eastern Asia (17.8 percent), and Europe (10.8 percent). The main origins of imports were in Northern America (33.2 percent of total imports), Eastern Asia (27.0 percent), and Europe (15.2 percent).

Change signals

Curated trends, signals or opportunities

Cooperatives in the region

Crypto for remittances in Argentina

Colombia and Brazil have 7 of the world’s top 10 cooperatives in education, health and social work.

In Brazil, health cooperatives provide medical and dental services to 17.7 million people, almost 10% of the country’s population (2011). Cooperatives are responsible for 37.2% of agricultural GDP and 5.4% of global GDP (2009).

Argentinian agricultural cooperatives are responsible for more than 20% of the national total of wheat exports (2010-2011)

Savings and credit cooperatives in Paraguay have assets of more than 2,100 million dollars, which represents almost 17% of the total of the national financial system (2010).

In Uruguay, cooperatives are responsible for 3% of GDP. They produce 90% of the milk, 34% of the honey and 30% of the wheat. 60% of its production is exported to more than 40 countries (2011)

The assets of financial cooperatives in El Salvador exceed 1,300 million dollars, which represents 9.3% of the total of the national financial system (2010)

Savings and credit cooperatives in Costa Rica own 8.5% of the assets of the national financial system (2011)

Savings and credit cooperatives in Ecuador have assets of almost 2,500 million dollars, which represents a participation of 9.12% in the total of the national financial system (2010).

| # of coops | # of coop members | # of jobs | coops per capita | coop members per capita | |

| Argentina | # of coops | 17.8 millions | 193,760 | 1 coop per 5,162 people | 1 in every 2 people |

| Brazil | 8,618 | 14.6 millions | 425,300 | 1 coop per 30,682 people | 1 in every 14 people |

| Uruguay | 6,828 | 1.3 millions | 11,103 | 1 coop per 931 people | 1 in every 3 people |

| Colombia | 3,653 | 6.3 millions | 139,093 | 1 coop per 15,507 people | 1 in every 8 people |

| Costa Rica | 3,205 | 860,855 | 17,599 | 1 coop per 13,298 people | 1 in every 6 people |

Source: World Cooperative Monitor 2021 (fiscal year of 2019, ranked by turnover over GDP per capita). Cooperativas de las Américas. Image: RCC.com

Argentinians have no other option than being creative to face the volatile economy. Open Zeppelin is one of their successful answers, a platform that allows the development and harboring of secure transactions using blockchain technology.

“Being born in Argentina should not set which currency I can charge with or invest in. Blockchain technology allows the creation of a new world financial system, open and digital, that will empower the people”, explains the platform’s founder and CEO, Demian Brener.

Source: MIT’s Innovators Under 35 Image: San Luis Press

Venezuelan mobile apps that emerged with the crisis

Bogota’s voluntary tax

App-based service companies like Uber may have reached much of the world, but not yet Venezuela, where they face government restrictions, US sanctions, years of hyperinflation and many other barriers. Instead, local business people and entrepreneurs have come together to launch their own apps, from food delivery “Yummy” and private car rides “Ridery” to “Provitared” where users donate, exchange and find medicines or “Te lo pongo Venezuela”, aimed to the diaspora abroad so they that can send products to their relatives in the country.

In 2020, 29,000 “Bogotanos” paid an additional voluntary tax to the Colombia’s capital city hall to help covering the new measures to face the coronavirus. This was a 62% increase comparing to the previous year, adding USD 280,000 to the administration’s budget.

The people of Bogotá have paid this voluntary tax since 2002, when the current mayor Professor Antanas Mockus first made this proposal to increase investment in citizen security. His administration collected USD 240,000. However, corruption claims during the following administration disencouraged citizens to continue contributing and the current mayoress faces the challenge of recovering their trust.

Source: Bogota’s voluntary tax Image: Infobae

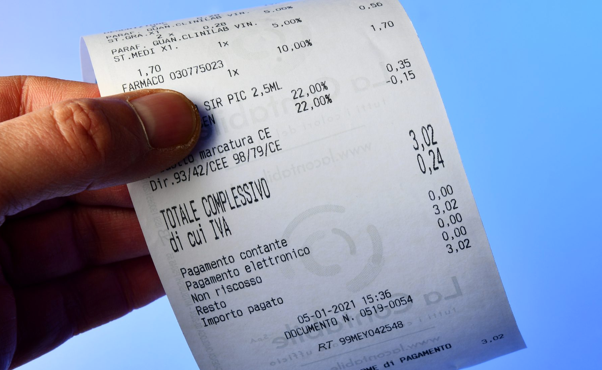

Paulista Invoice

Complimentary Currency in Costa Rica

The government of the state of São Paulo (Brazil) implemented in 2007 the “Tax Citizenship” program – popularly known as “Nota Fiscal Paulista” -, which provides economic incentives for citizens who request an official electronic invoice for all their purchases, consequently increasing the tax collection in the retail sector.

This is Brazil’s main program to combat tax evasion, with a proved 12% increase in the state tax collection in the first 7 years – representing an additional USD 113 million in taxes to the state of São Paulo.

Source: O Impacto do Programa Nota Fiscal Paulista na Expansão das Receitas Tributárias do Estado (2015) Image: Recovery

“Verdes” is the complementary currency of Monteverde (Costa Rica), proposed during the first months of the pandemic when tourism vanished and most of the families in the area were left without work. This led the community to think of solutions and as a result they created their own currency, allowing people to activate bartering and provide for their basic needs.

Complementary currencies have existed for thousands of years, but are currently created with the purpose of constituting economic systems that are less speculative and that improve the social welfare of the territories in which they are used.

Source: Proofing Future Image: Recovery

Change signals

Initiative spotlight

Banco Palmas

Brazil’s first community development bank

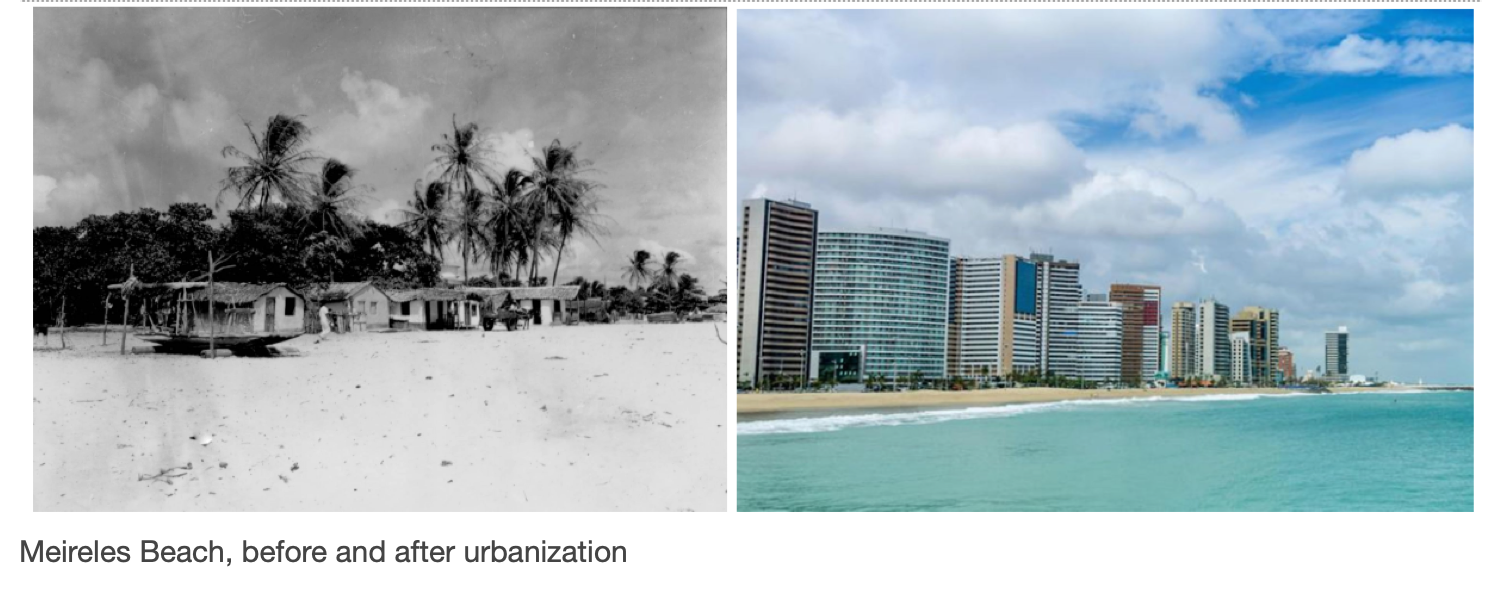

Fortaleza, a 2.6 million inhabitants capital city in Brazil’s Northeast, is a major tourist destination attracting around 2 million visitors per year to its whitesand beaches, blue-water ocean and warm temperatures.

The city’s growth, however, has come with a price. It was based on an urbanization policy in the 1970s that displaced fishermen and low-income families from the coastal region to suburban and undeveloped swampy areas, far from schools and city jobs and devoid of basic urban facilities such as public transportation, water supply, sanitation and electricity.

In the 1980s, as Brazil’s society was going through a re-democratization process after many years of an authoritarian military regime, the residents of Conjunto Palmeiras created a neighborhood association that fought for basic infrastructure and public services across the following decade.

In 1997, 90% of the neighborhood’s resident families lived on less than $4 USD a day, 70% of the adult population was illiterate, and at least 1,200 children of school age were not in school. On another perspective, though, the neighborhood association realized that they were spending more than $1 million USD per month mostly outside of Conjunto Palmeiras. As Joaquim de Melo, one of the community leaders explained, “we discovered one important thing: we remained poor not only because we had little money, but mostly because we were spending it outside the favela. An instrument had to be created for the community to both produce and consume locally” (Le Monde, May 26th 2010).

It was under this context that Banco Palmas (Palmas Bank), Brazil’s first community bank, was created.

Image source: Skyscrapercity.com and Mercure Fortaleza

What are community development banks?

Community banks are network-driven solidary financial services – including loans, insurance, savings, financial education and others -, aimed at generating work and income by reorganizing local economies.

Some characteristics of community banks are:

- The community itself decides to create the bank, becoming its manager and owner;

- It always operates with two lines of credit: one in the country’s currency and the other in local social currency;

- Its lines of credit encourage the creation of a local production and consumption network, promoting the endogenous development of the territory;

- It supports local businesses with a commercialization strategy that includes fairs, solidarity stores, commercialization center, among others;

- It operates in territories characterized by a high degree of social exclusion and inequality;

- It is aimed at a public characterized by a high degree of social vulnerability, especially those beneficiaries of governmental social programs with compensatory policies;

- Their short-term financial sustainability is usually subsidized to guarantee their longer-term viability.

The expansion of community development banks

In 2003, Banco Palmas created the Instituto Palmas (Palmas Institute) with the objective of replicating the bank’s experiences throughout Brazil. Ten years later, a network of 103 community banks was spread across 19 Brazilian states. In 2014, they created Instituto E-Dinheiro Brasil, a fintech organization dedicated to digitizing community banks, giving rise to the Brazilian Network of Solidarity Digital Banks, today with 70 members.

The experience of Banco Palms is an inspiration for similar models developed across the world in the last decades.

2022 REPORT