2022 report

Change & Emergence

in Latin America

Prosperity

Current Situation

A snapshot of trust justice and security

A. Interpersonal trust and inequality.

People in unequal societies trust each other to a much smaller extent than people do in more equal communities.

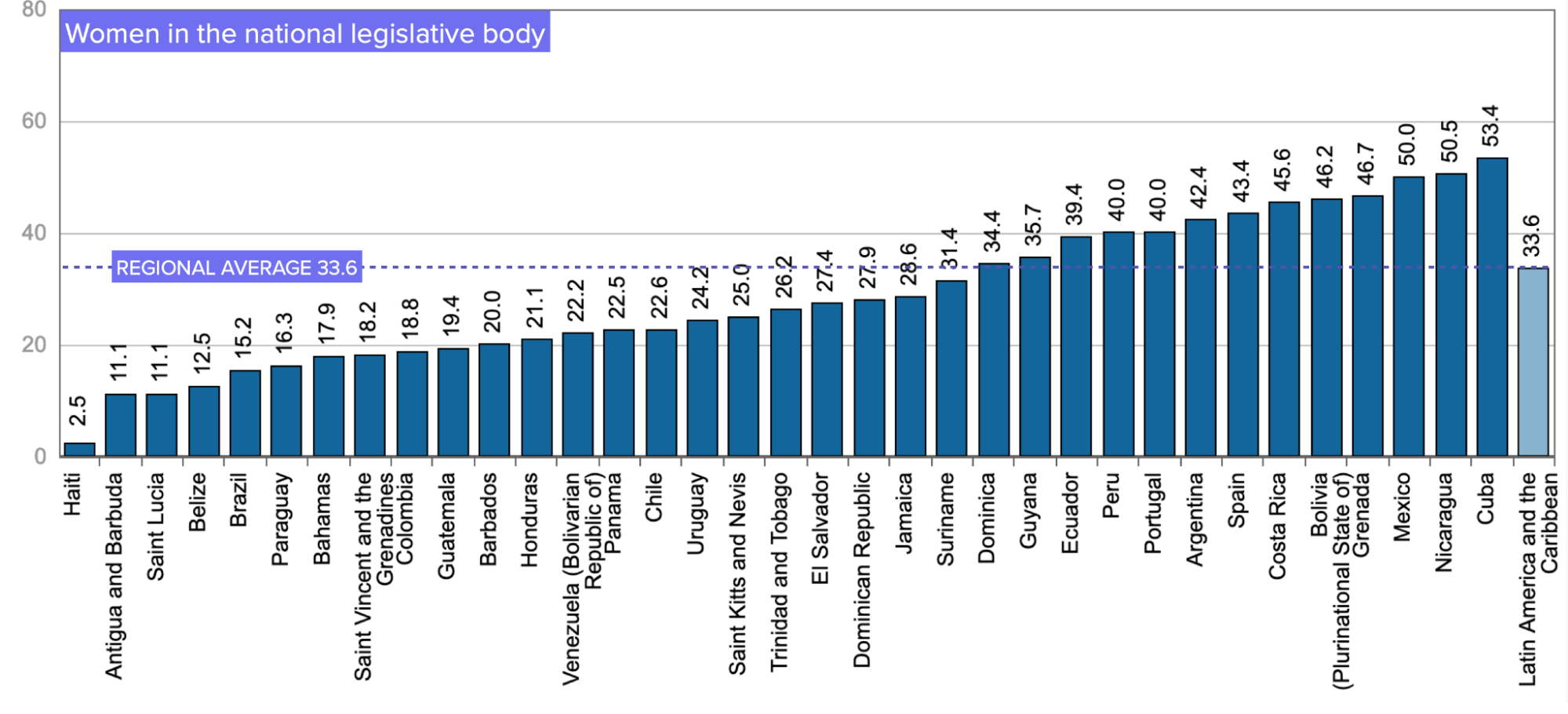

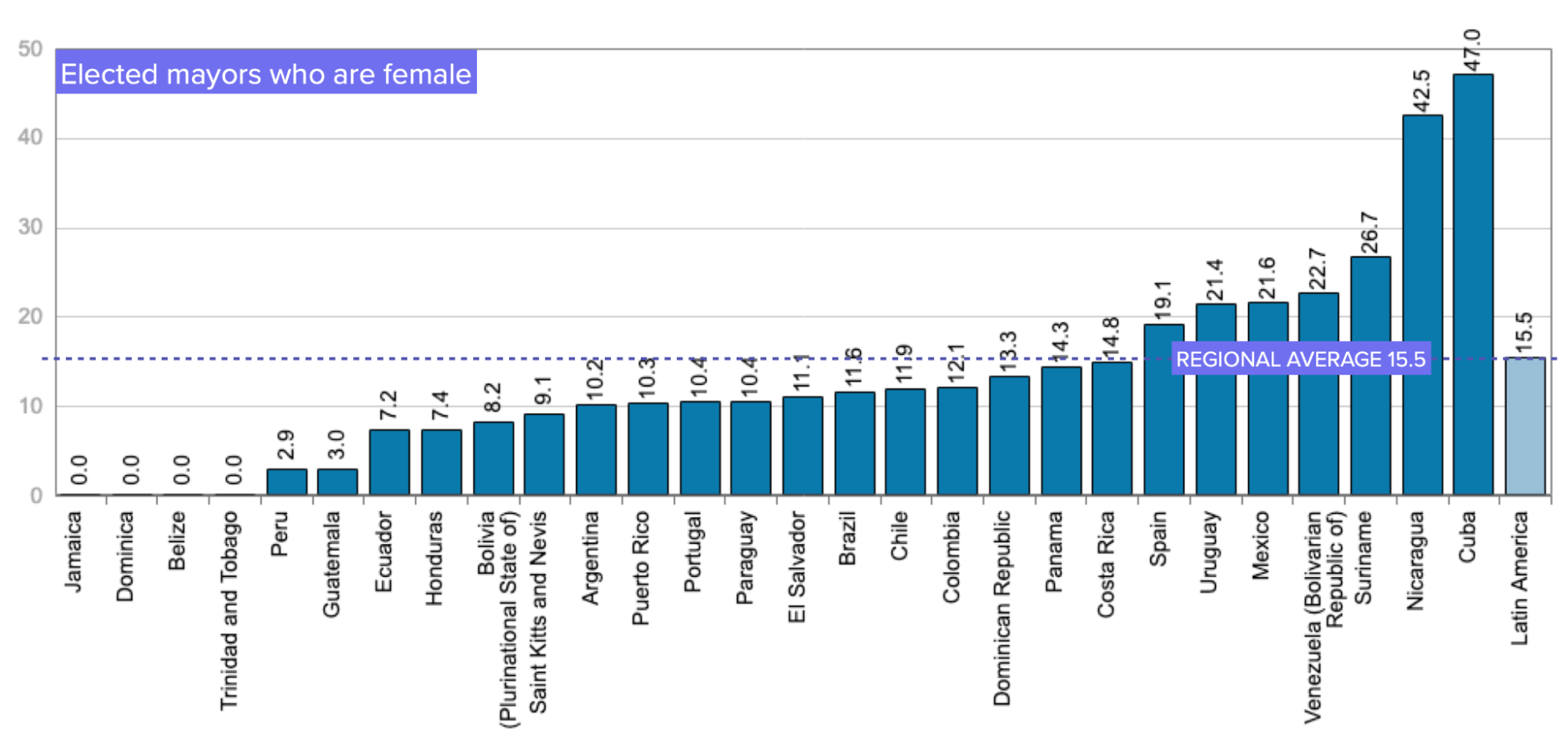

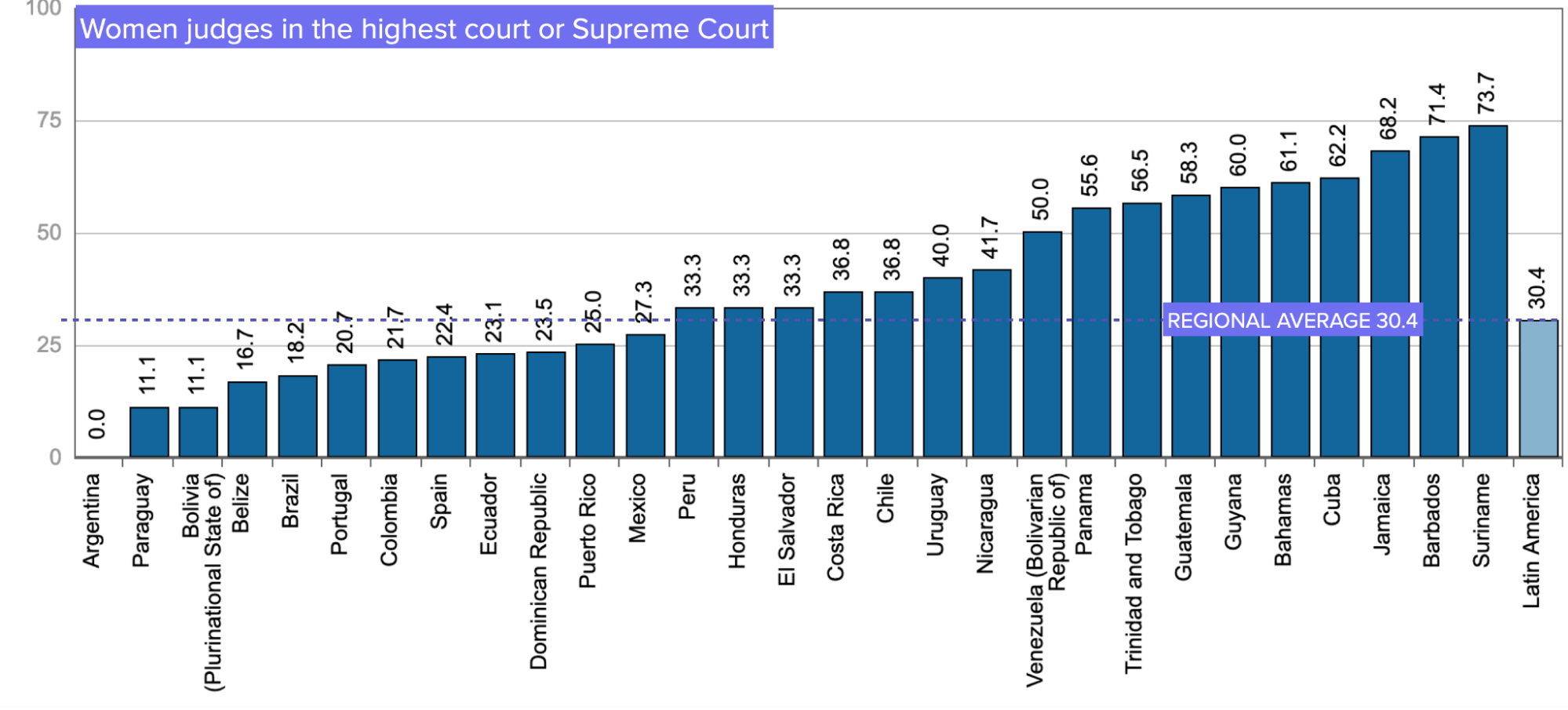

B. Gender equality in the region has a long road ahead.

Although government affirmative actions are beginning to show some progress in cabinet positions and congresses. On the other hand, businesses are quite behind; women hold only 15% of management positions and own only 14% of companies

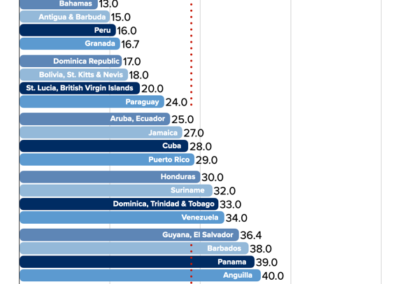

C. Land distribution inequality.

Latin America is the region of the world with the greatest inequality in the distribution of land, with small minorities monopolizing large estates and the majority of farmers without land or exploiting small holdings of land.

D. Vulnerability has increased

An estimated 491 million Latin Americans were living with income equivalent to three poverty lines or less. This means that 8 out of 10 Latin Americans are vulnerable.

There are different ways to measure inequality and although Gini Index and income poverty are widely used they fall short of conveying the multiple factors and forces that scaffold an unjust system that affects the region. We will try to shed some light diving into these and other proxies.

Source: 3.1 Gallup Poll and Our World in Data: trust: is people reporting that “most people can be trusted”, inequality is Gini Index. 3.2 CEPALSTAT as of september 2022. 3.3 ElordenMundial.com with data form Oxfam, made by Abel Gil Lobo. 3.4 Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of the Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

Current Situation

Selected problems snapshot

Introduction

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipiscing elit erat quam nisl suscipit, sollicitudin conubia ornare ac netus et volutpat a fermentum. Cubilia sodales ultricies auctor quam cursus sem praesent netus aenean nec, morbi laoreet sed pellentesque dictumst blandit ante potenti hendrerit commodo, penatibus suspendisse mattis lacus sagittis velit quis donec purus. Dapibus potenti diam quis mattis curae facilisis faucibus velit, aliquet commodo porttitor duis gravida suscipit litora taciti aliquam, mauris dictum mus porta neque cras pellentesque.

Current Situation

Selected problems snapshot

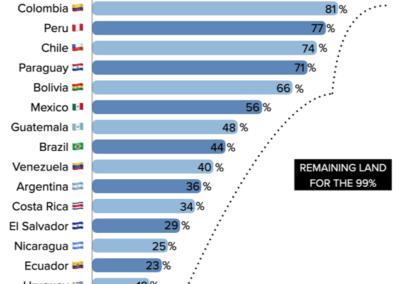

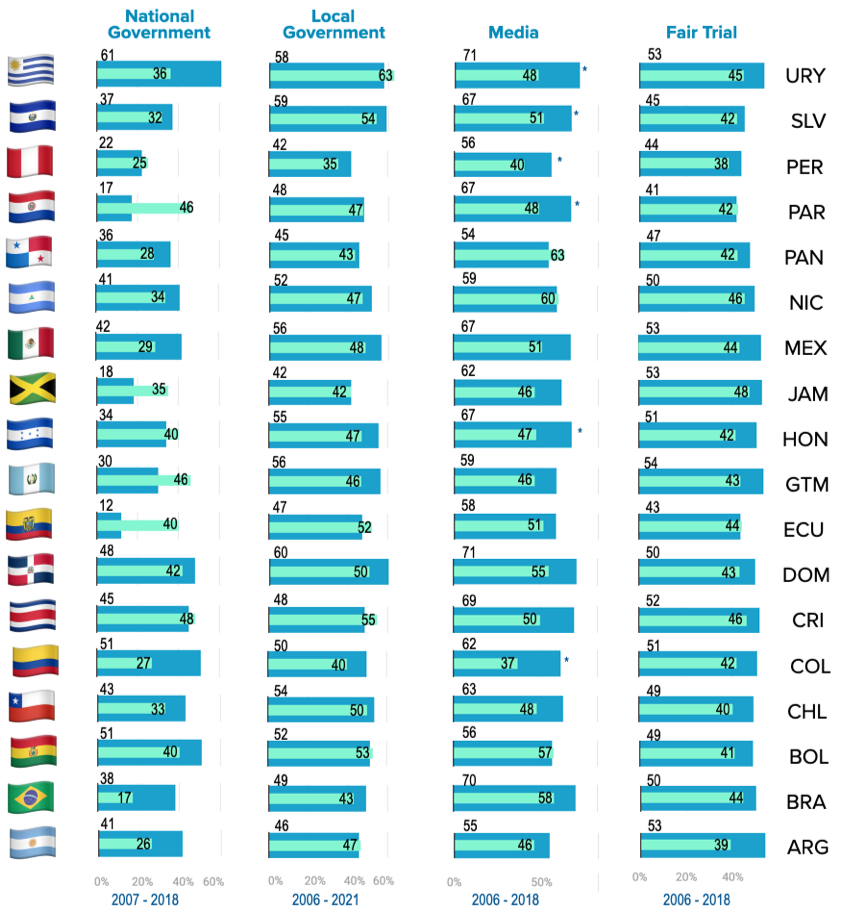

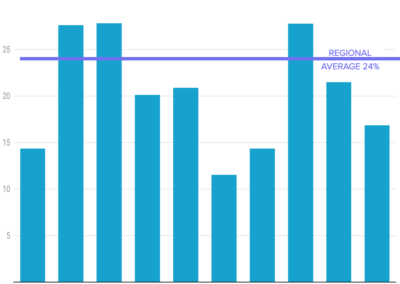

Trust challenges and priorities by country

The first figure shows the top priorities in each country according to its citizens; clustering them by bigger topics quickly reveals that their bigger concerns are on security issues and economic instability. The next figure compares how trust has shifted in a decade, with the most dramatic drop being in national governments and the media, nevertheless, there are some outstanding exceptions to this trend in Paraguay, Jamaica, Guatemala, Ecuador, and Costa Rica. There is also a slight fall in trust in local governments and a fair trial, it isn’t much but as the drop is less steep it signals entry points and places to build back trust in institutions.

Sources and references: Lorem ipsum que estás en los cielos

Citizens’ trust: behavior over time

Outside bar is the first year it was measured and inner bar is the latest year

Sources: Gallup World Poll (2018) and Vanderbilt University’s AmericasBarometer: LAPOP Data Playground. *2021 poll data.

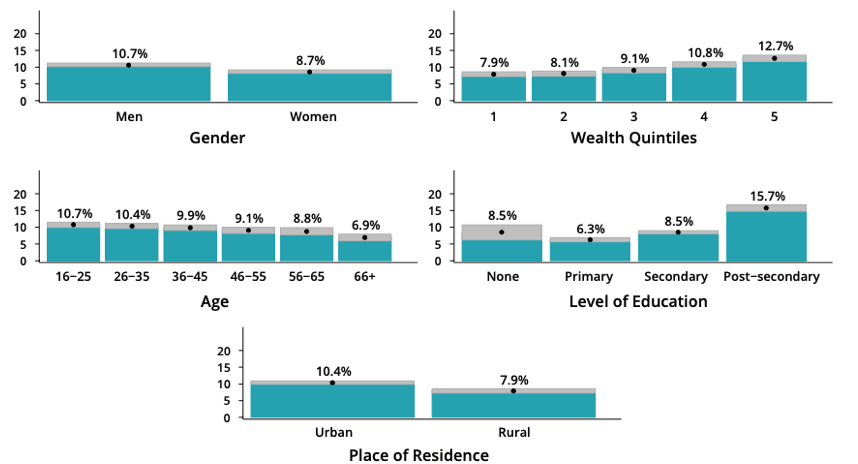

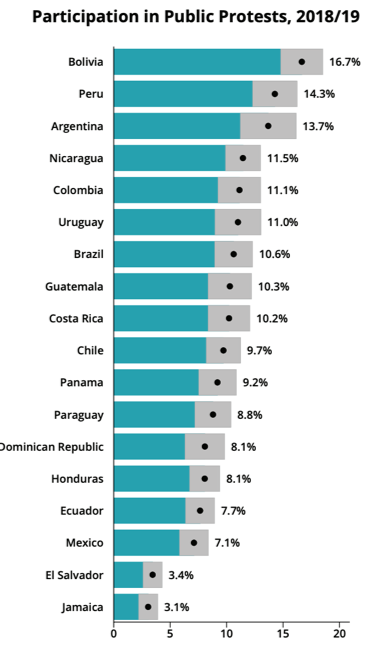

Civic engagement

Participation in public protests is higher among male, wealthy, young, educated, and urban individuals

On average, men are more likely to report protest participation compared to women (10.7% and 8.7%, respectively). Among wealth quintiles, the highest levels of protest participation are found in the richest quintile. Younger cohorts also express higher participation in public protests compared to older cohorts. More educated individuals participate more in public protests than less educated individuals. Lastly, individuals who live in urban areas express greater participation in public protests compared to rural residents

Corruption and accountability in government

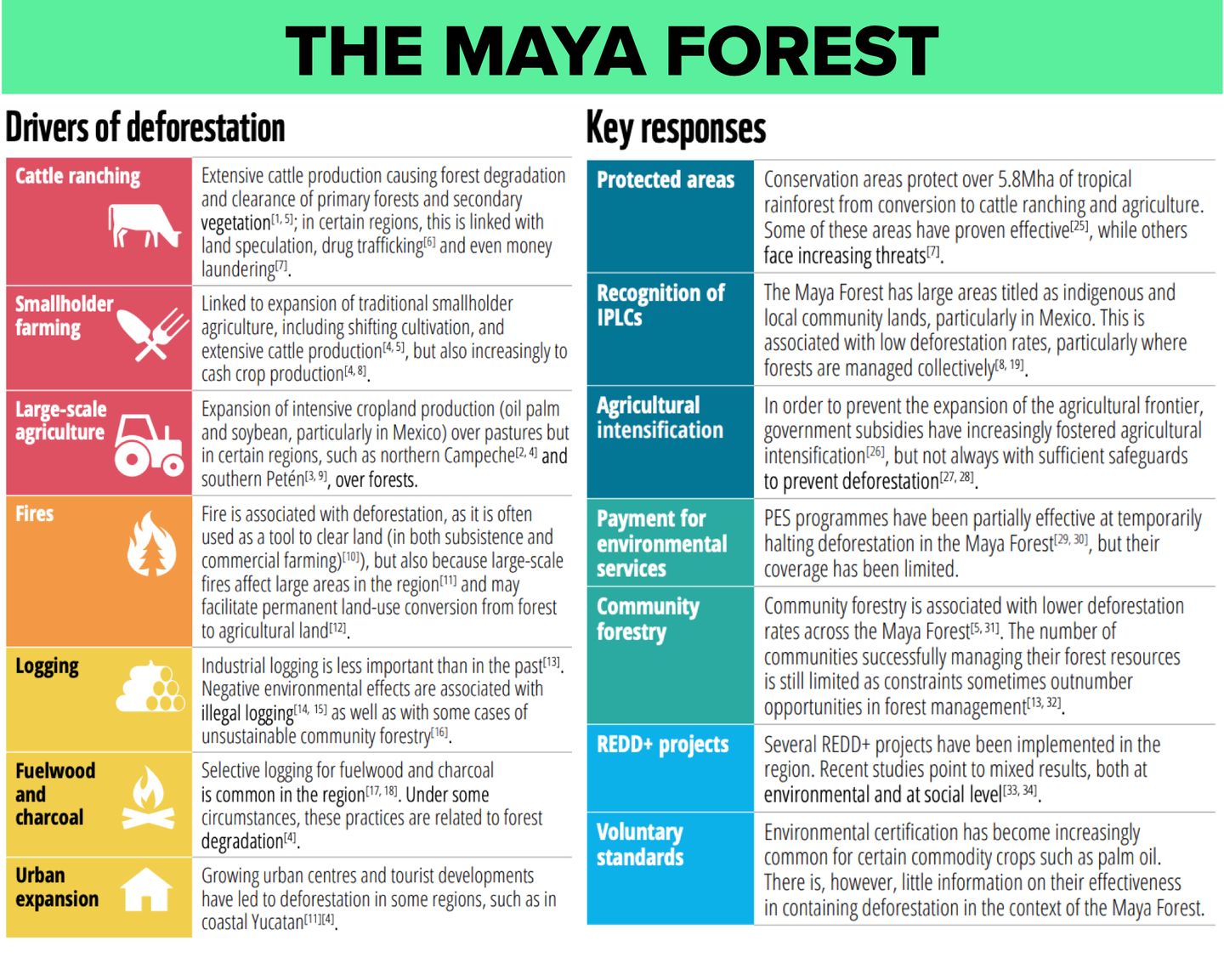

The Enterprise Surveys are firm-level surveys of a representative sample of an economy’s private sector. The surveys cover a broad range of business environment topics in this case corruption as a constraint for doing business against the percentage of transactions where a gift was requested.

A. Corruption perception and bribery depth

The Open Budget Survey assesses the three components of a budget accountability system:

- Public availability of budget information

- Opportunities for the public to participate in the budget process

- The role and effectiveness of formal oversight institutions

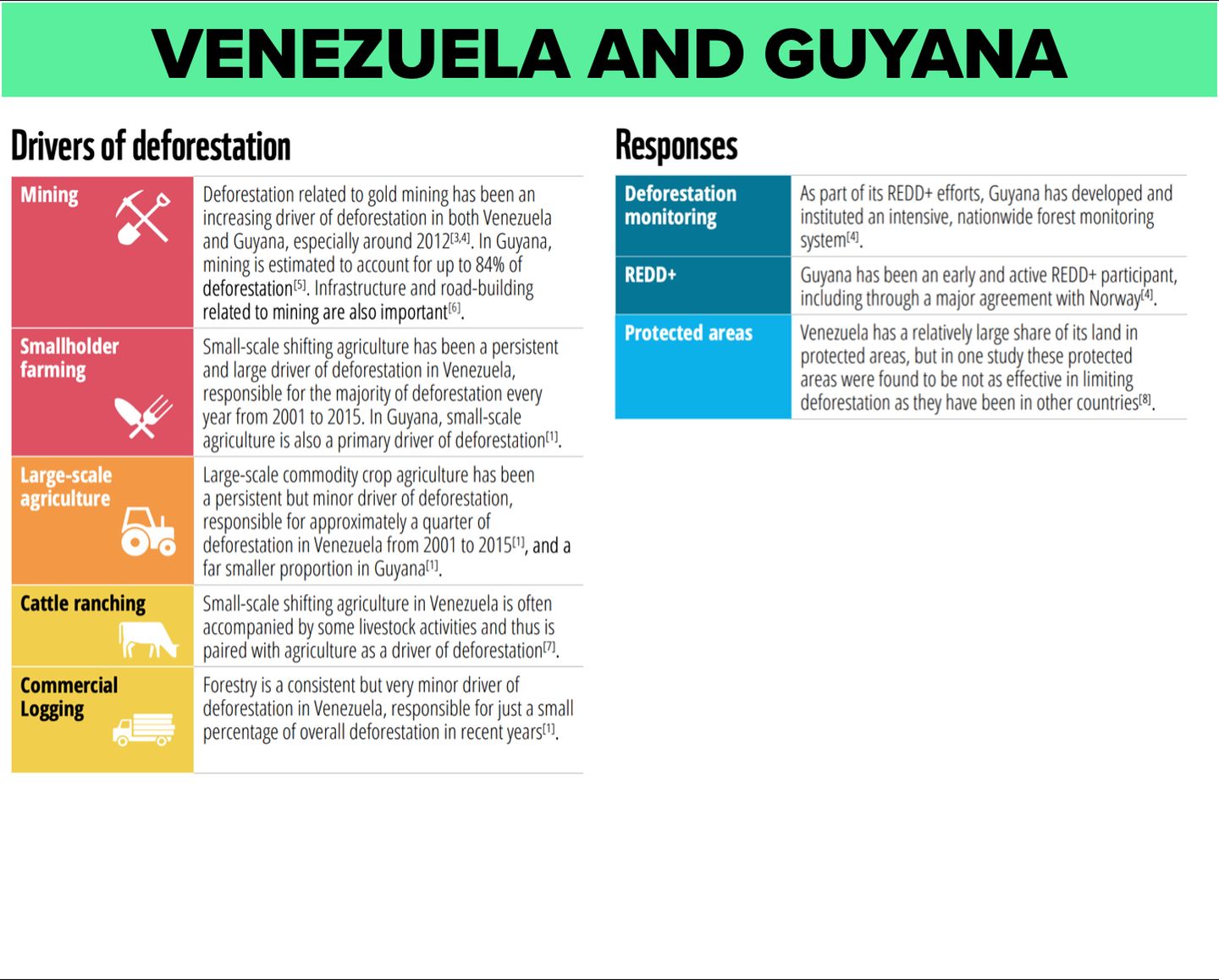

B. Open Budget Index

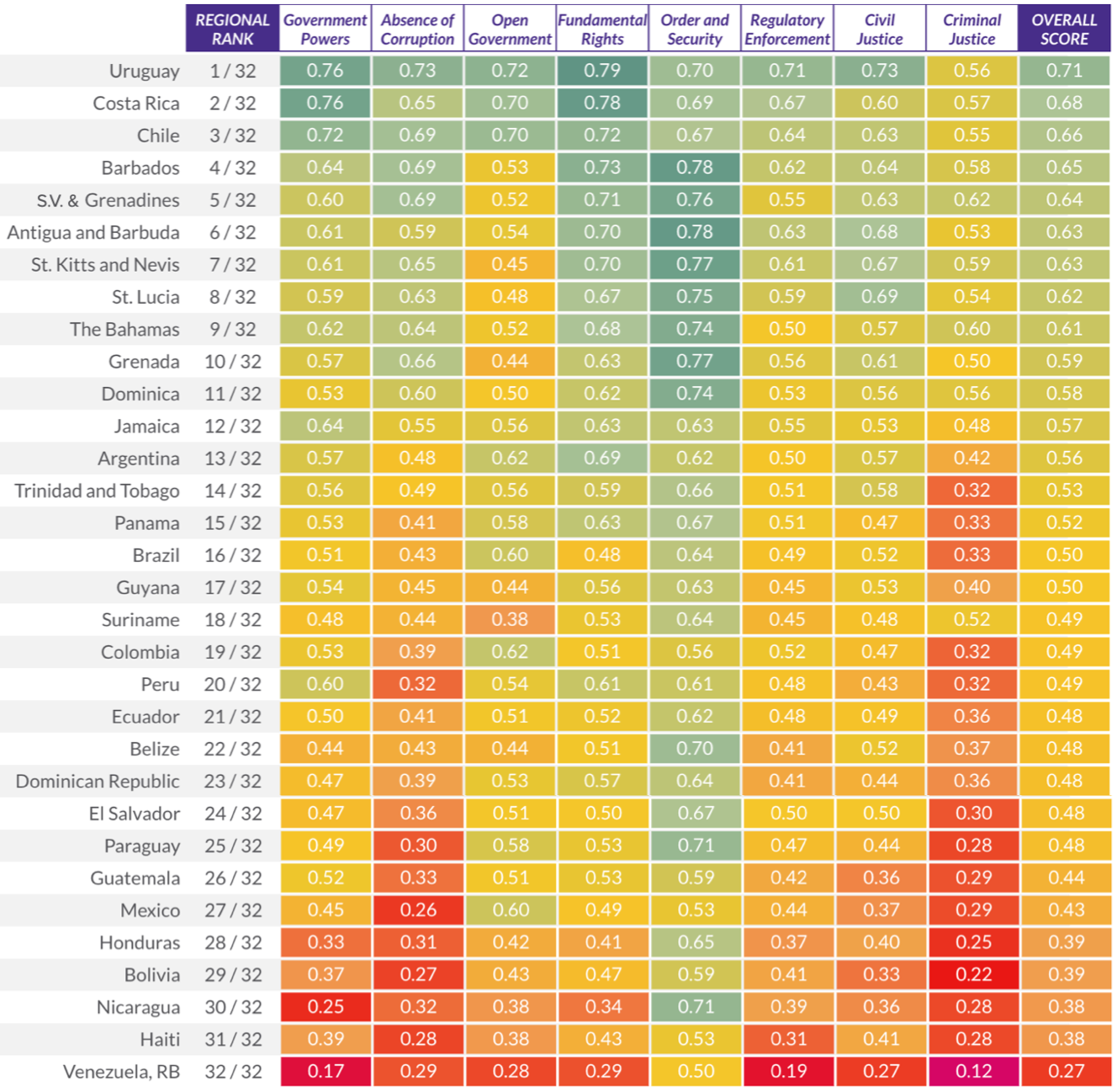

Rule of Law Index

The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index® relies on national surveys of more than 138,000 households and 4,200 legal practitioners and experts to measure how the rule of law is experienced and perceived worldwide.

More countries declined than improved in overall rule of law performance for the fourth consecutive year. In a year dominated by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

- Constraints on government powers fell and civic spaces diminished amid the pandemic.

- During the last year, 70% of countries covered by the Index declined in Constraints on Government Powers.

- Over the past year, 82% of countries in the Index experienced a decline in at least one dimension of civic space (civic participation, freedom of opinion and expression, and freedom of assembly and association).

Government power

The extent to which those who govern are bound by law. it comprises the means, both constitutional and institutional, by which the powers of the government and its officials and agents are limited and held accountable under the law. it also includes non-governmental checks on the government’s power, such as a free and independent press.

1.1 government powers are effectively limited by the legislature

1.2 government powers are effectively limited by the judiciary

1.3 government powers are effectively limited by independent auditing and review

1.4 government officials are sanctioned for misconduct

1.5 government powers are subject to non-governmental checks

1.6 transition of power is subject to the law

Absence of corruption

The factor considers three forms of corruption: bribery, improper influence by public or private interests, and misappropriation of public funds or other resources. these three forms of corruption are examined with respect to government officers in the executive branch, the judiciary, the military, police, and the legislature.

2.1 government officials in the executive branch do not use public office for private gain

2.2 government officials in the judicial branch do not use public office for private gain

2.3 government officials in the police and the military do not use public office for private gain

2.4 government officials in the legislative branch do not use public office for private gain

Open government

Measures the openness of government defined by the extent to which a government shares information, empowers people with tools to hold the government accountable, and fosters citizen participation in public policy deliberations. this factor measures whether basic laws and information on legal rights are publicized and evaluates the quality of information published by the government.

3.1. publicized laws and government data

3.2 right to information

3.3 civic participation

3.4 complaint mechanisms

Fundamental rights

Recognizes that a system of positive law that fails to respect core human rights established under international law is at best “rule by law,” and does not deserve to be called a rule of law system. since there are many other indices that address human rights, and because it would be impossible for the index to assess adherence to the full range of rights, this factor focuses on a relatively modest menu of rights that are firmly established under the united nations universal declaration of human rights and are most closely related to rule of law concerns.

4.1 equal treatment and absence of discrimination

4.2 the right to life and security of the person is effectively guaranteed

4.3 due process of the law and rights of the accused

4.4 freedom of opinion and expression is effectively guaranteed

4.5 freedom of belief and religion is effectively guaranteed

4.6 freedom from arbitrary interference with privacy is effectively guaranteed

4.7 freedom of assembly and association is effectively guaranteed

4.8 fundamental labor rights are effectively guaranteed

Order and security

Measures how well a society ensures the security of persons and property. security is one of the defining aspects of any rule of law society and is a fundamental function of the state. it is also a precondition for the realization of the rights and freedoms that the rule of law seeks to advance.

5.1 crime is effectively controlled

5.2 civil conflict is effectively limited

5.3 people do not resort to violence to redress personal grievances

regulatory enforcement: measures the extent to which regulations are fairly and effectively implemented and enforced. regulations, both legal and administrative, structure behaviors within and outside of the government. this factor does not assess which activities a government chooses to regulate, nor does it consider how much regulation of a particular activity is appropriate. rather, it examines how regulations are implemented and enforced.

6.1 government regulations are effectively enforced

6.2 government regulations are applied and enforced without improper influence

6.3 administrative proceedings are conducted without unreasonable delay

6.4 due process is respected in administrative proceedings

6.5 the government does not expropriate without lawful process and adequate compensation

Civil justice

Measures whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice system. it measures whether civil justice systems are accessible and affordable as well as free of discrimination, corruption, and improper influence by public officials. it examines whether court proceedings are conducted without unreasonable delays and whether decisions are enforced effectively. it also measures the accessibility, impartiality, and effectiveness of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms.

7.1 people can access and afford civil justice

7.2 civil justice is free of discrimination

7.3 civil justice is free of corruption

7.4 civil justice is free of improper government influence

7.5 civil justice is not subject to unreasonable delay

7.6. civil justice is effectively enforced

7.7 alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are accessible, impartial, and effective

Criminal justice

Evaluates a country’s criminal justice system. an effective criminal justice system is a key aspect of the rule of law, as it constitutes the conventional mechanism to redress grievances and bring action against individuals for offenses against society. an assessment of the delivery of criminal justice should take into consideration the entire system, including the police, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, and prison officers.

8.1 criminal investigation system is effective

8.2 criminal adjudication system is timely and effective

8.3 correctional system is effective in reducing criminal behavior

8.4 criminal system is impartial

8.5 criminal system is free of corruption

8.6 criminal system is free of improper government influence

8.7. due process of the law and rights of the accused

Gender equity in government

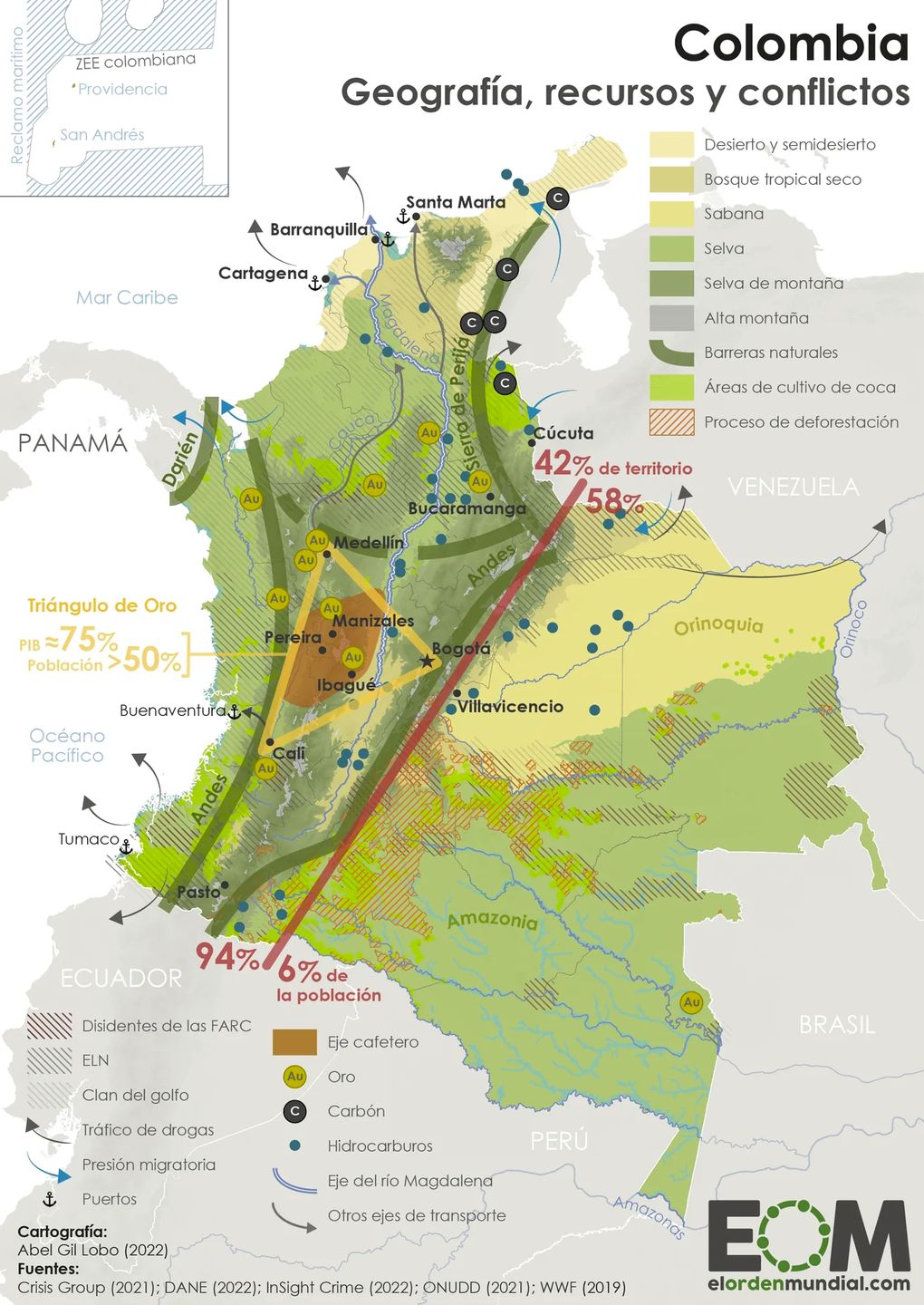

Land inequality

According to Oxfam’s 2016 report on land and inequality in Latin America, the region has the most inequality on the planet. Applying the Gini coefficient (where 0 is homogeneous and 1 completely unequal), Latin America obtains a 0.79 in land distribution, compared to 0.57 in Europe, 0.56 in Africa or 0.55 in Asia. Although Oxfam’s data may seem old, the lack of deep reforms in the agricultural sector is the norm in a large part of Latin American countries, where little change has been registered during the last decades.

Throughout the region, 1% of agricultural holdings concentrate slightly more than 50% of the available agricultural land, although this distribution is not homogeneous throughout Latin America either. The Andean countries tend to have concentrations of land in the hands of the top 1% with more than 60 or 70% land, while the less extensive countries (such as Uruguay and the Central American States, but also Ecuador) tend to have a distribution of the most balanced land.

At the extremes are Colombia and Uruguay, the first with 1% of the large landowners monopolizing 81% of the agricultural area, while in the second country that 81% of the land is owned by 99% of the farms. smaller.

The land problem has been the great Latin American problem for decades. Access to land by peasant masses, or the struggle against them to preserve the privileges of the elites, is at the origin of numerous conflicts, coups and revolutions in Latin America. They highlight, for example, the appearance of armed groups such as the FARC in Colombia or the Sandinista guerrilla in Nicaragua, the intervention of the CIA and the US in different countries or the colonization of new lands, with the consequent pressure on indigenous territories and virgin lands.

In Colombia, the unequal distribution of land is at the origin of the armed conflict that the country has suffered for nearly half a century. The small peasants were organizing themselves in marginal territories of the jungle while the communist ideology was impregnating their claims against a hostile State. In this context, the FARC and another handful of criminal organizations would emerge. With small unprofitable farms, coca cultivation became a viable way out of the poor situation of many farmers. While insurgent groups and coca growers intermingled, state pressure led to the colonization of new lands, starting a cycle of deforestation, coca cultivation and guerrillas that still shakes the peripheral territories of Colombia.

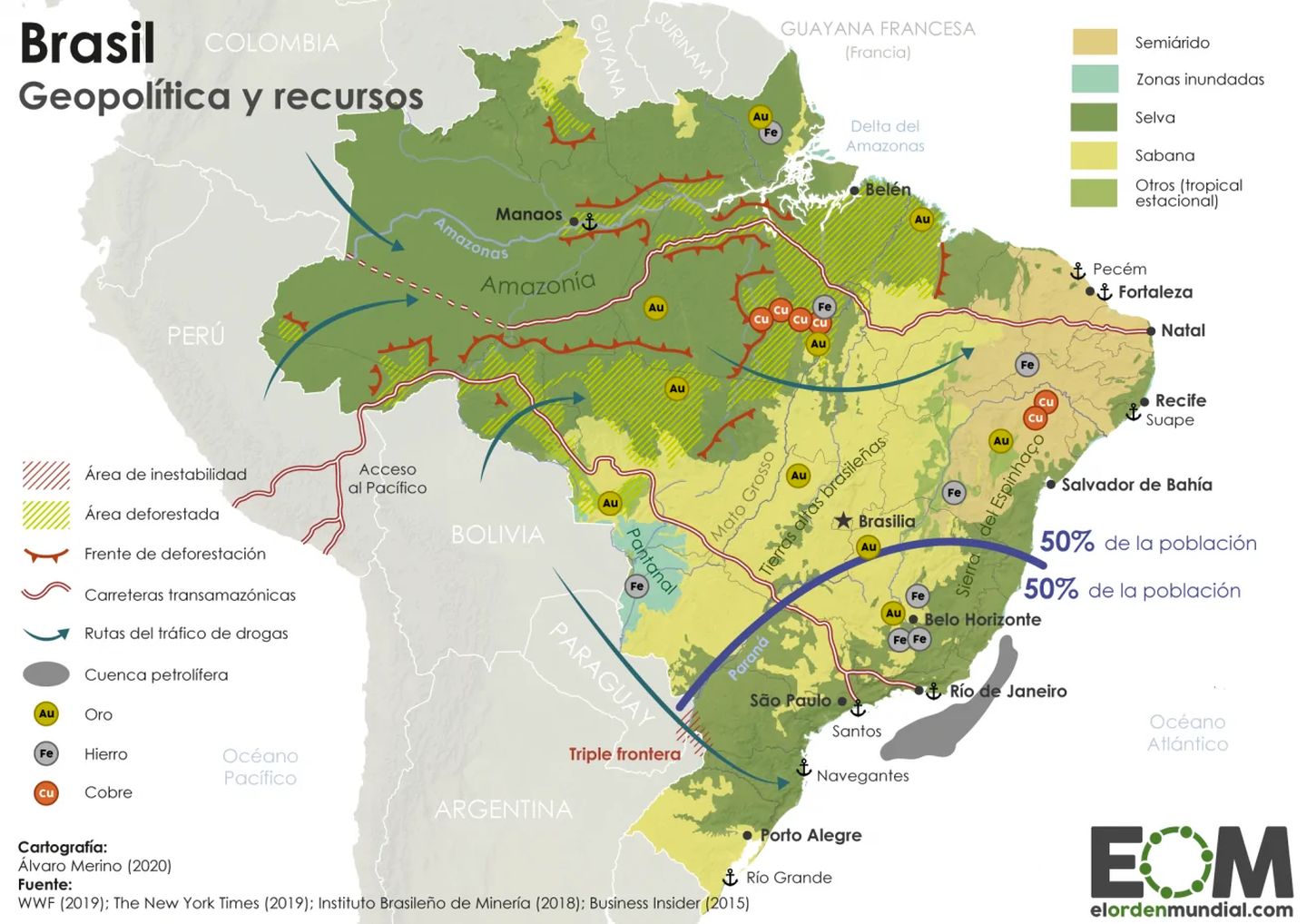

The colonization of new lands has taken place throughout Latin America, frequently with confrontations with the indigenous peoples who inhabit them. This is the case of Brazil, which has promoted the colonization of the Amazon basin to reduce social pressure, but at the cost of creating a vast lawless region where settlers and indigenous peoples conflict over land.

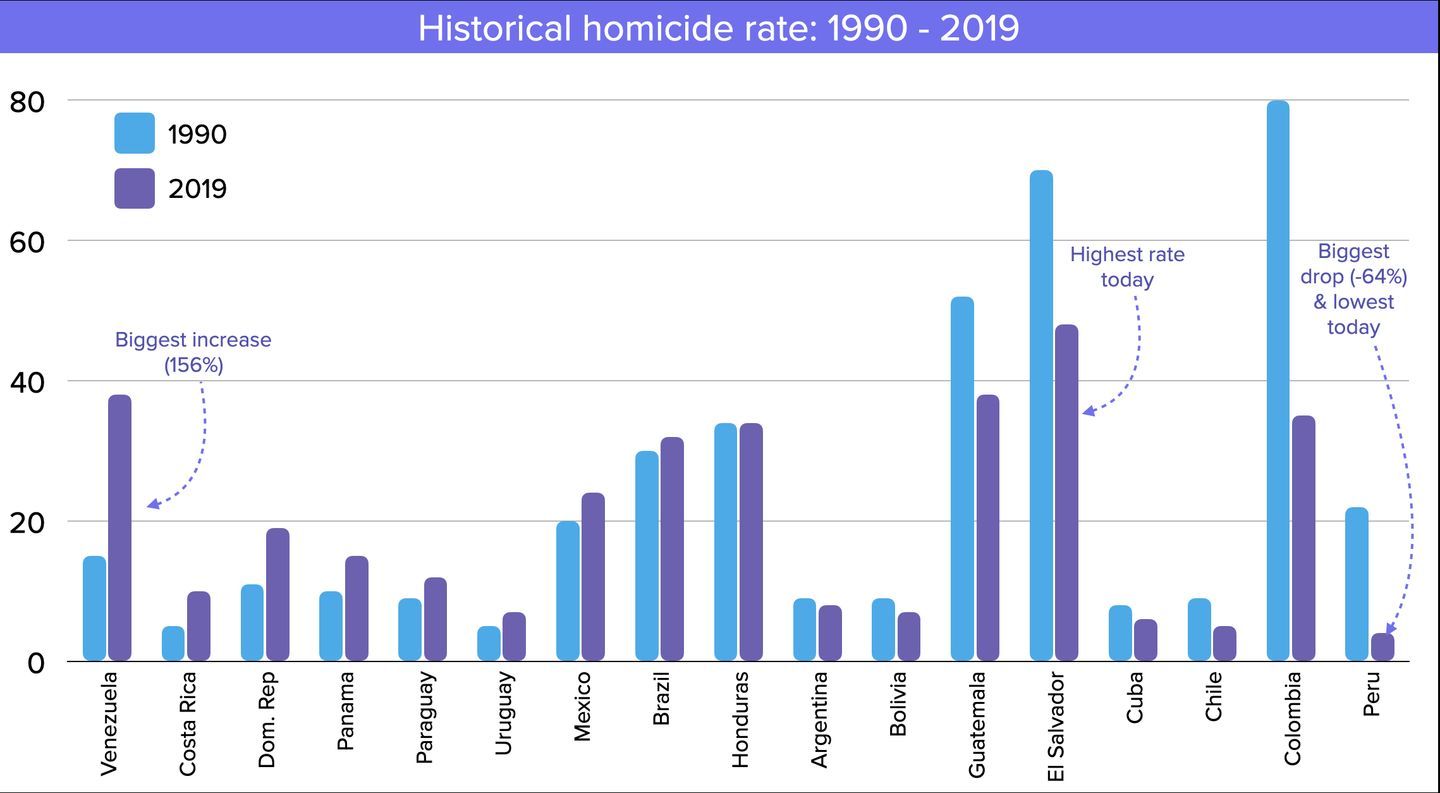

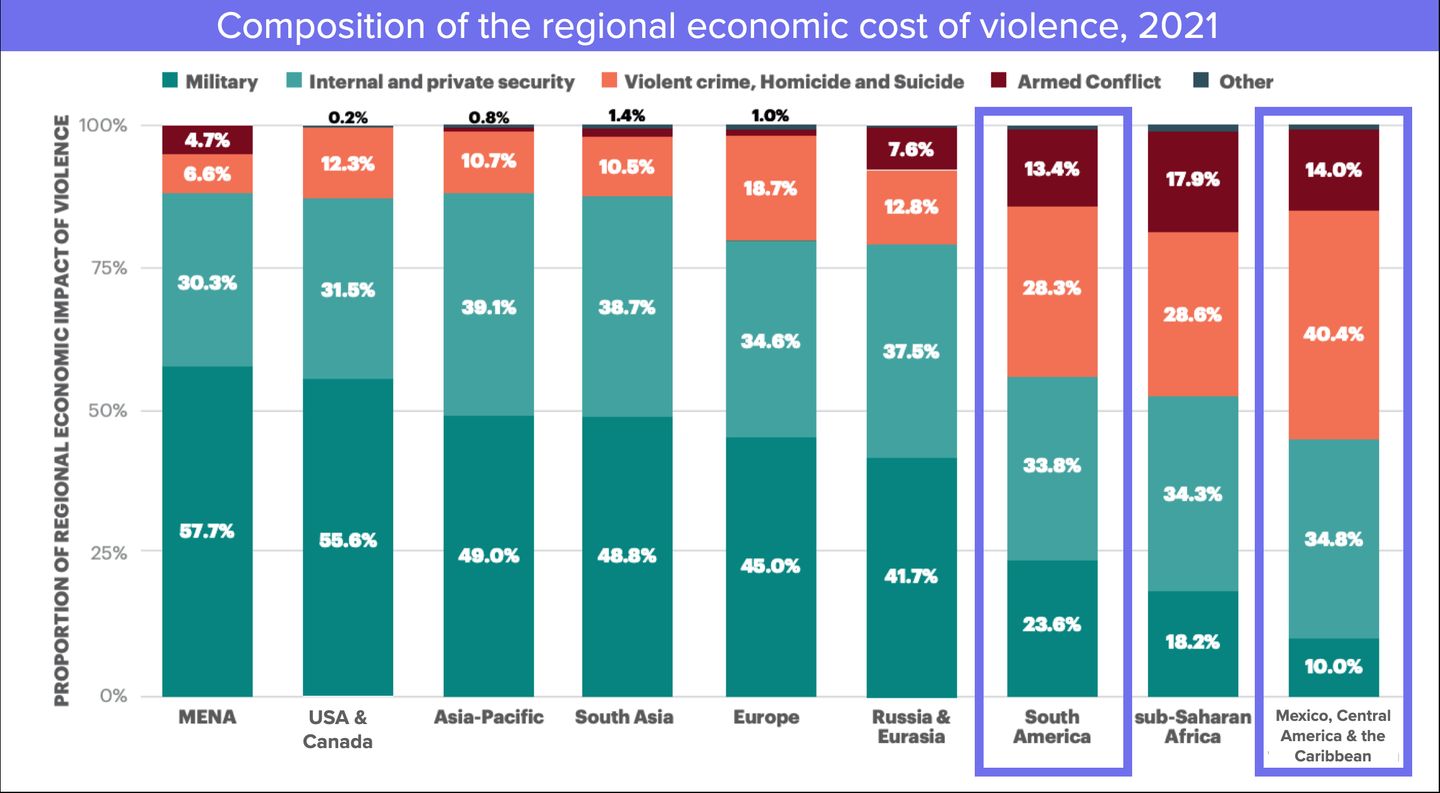

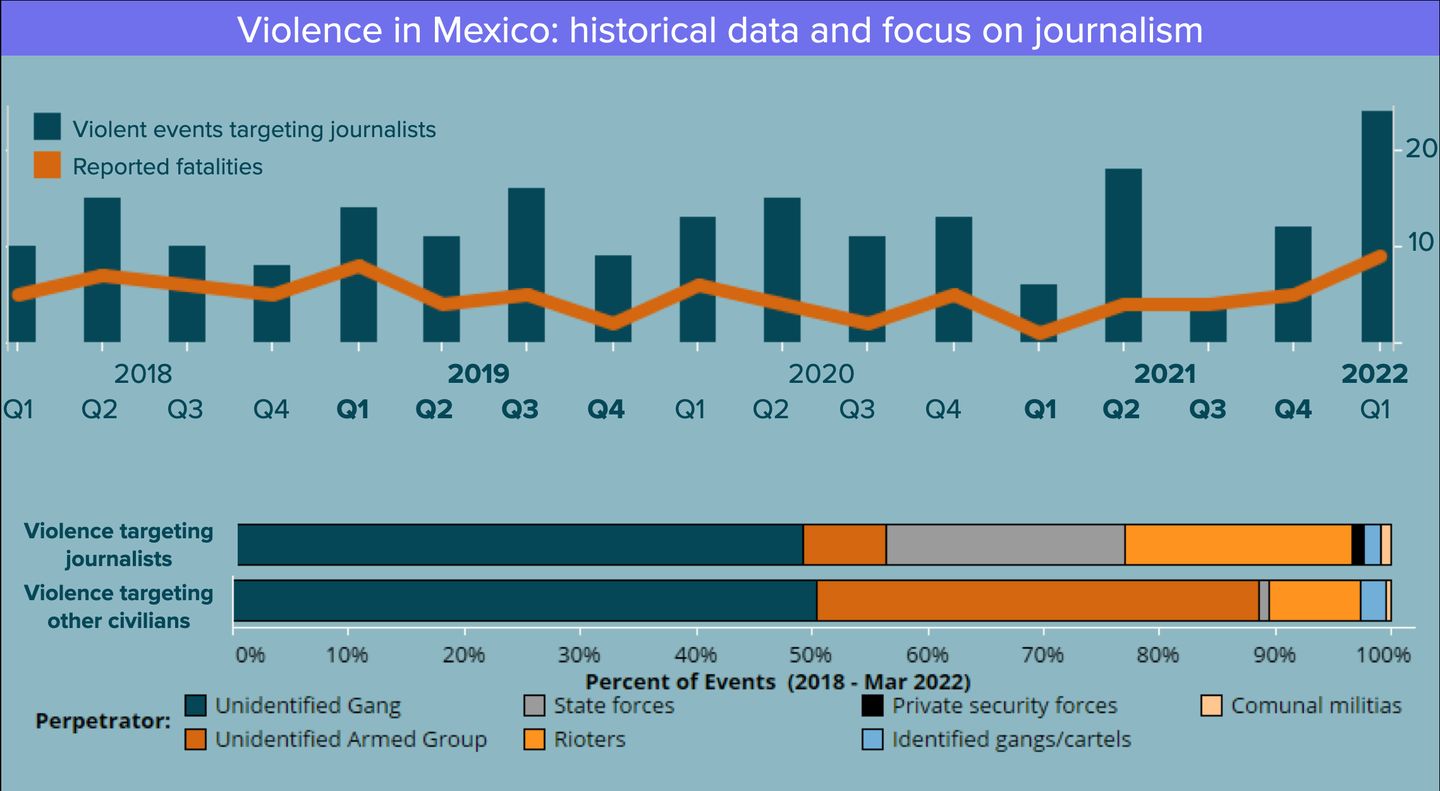

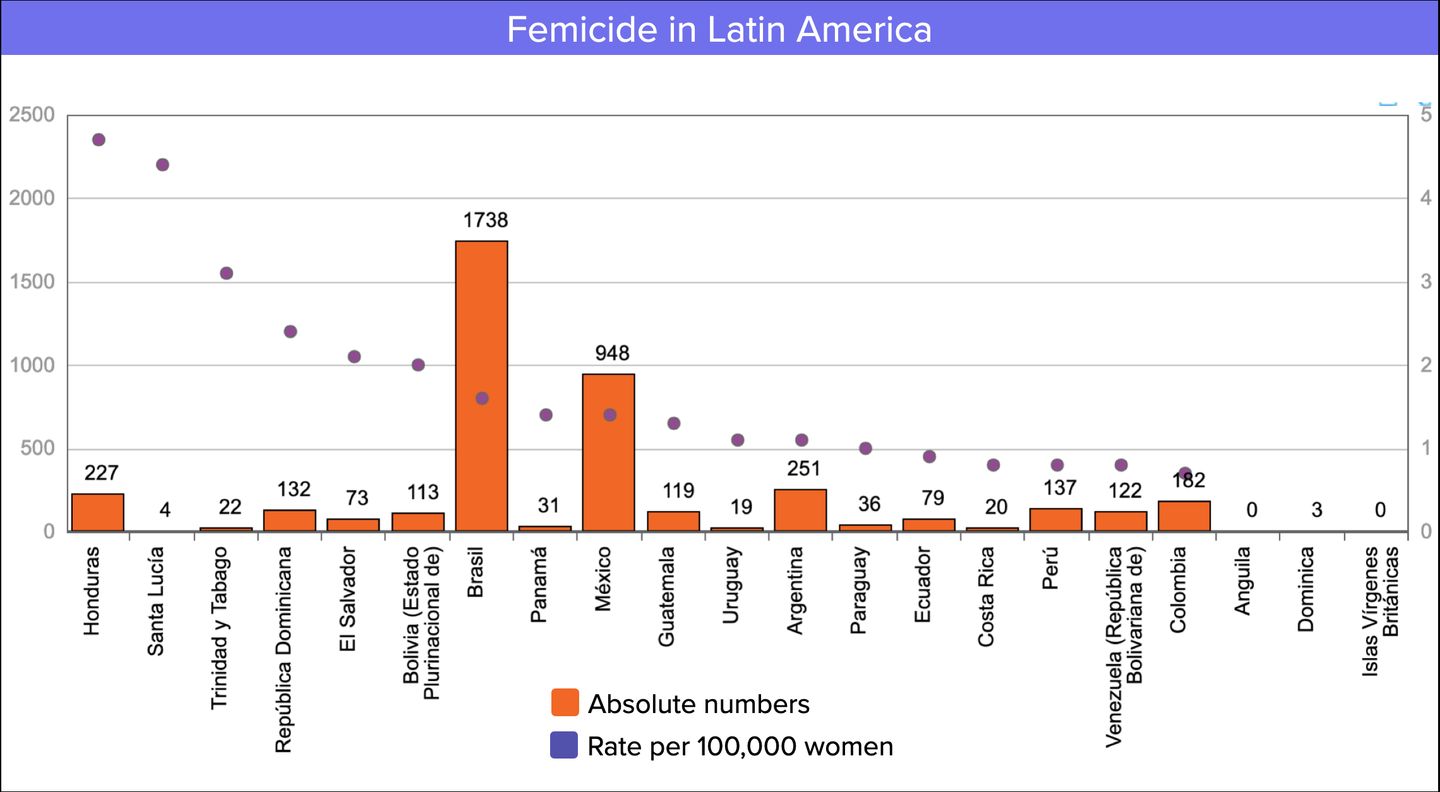

A complex violence landscape

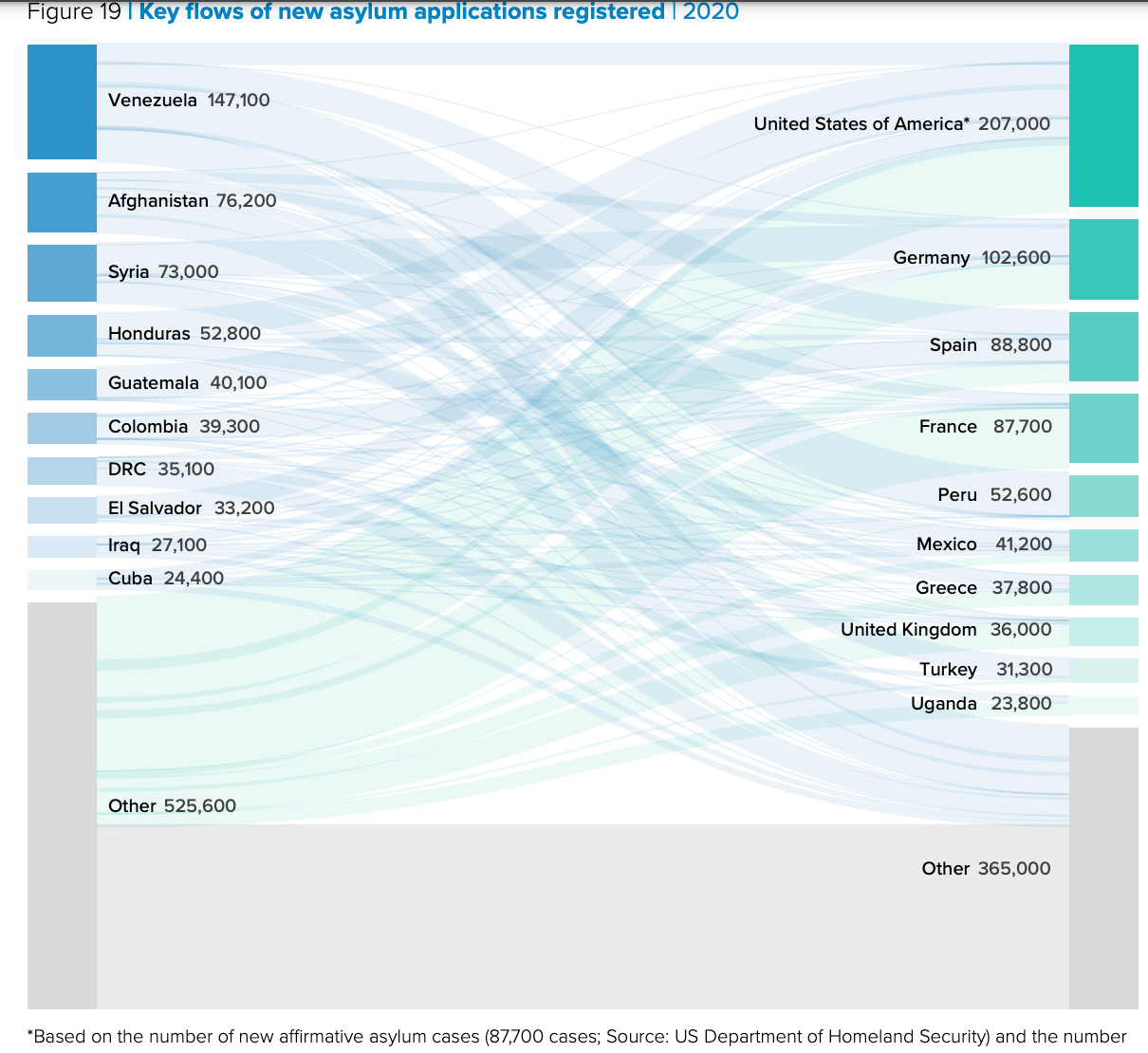

Migration

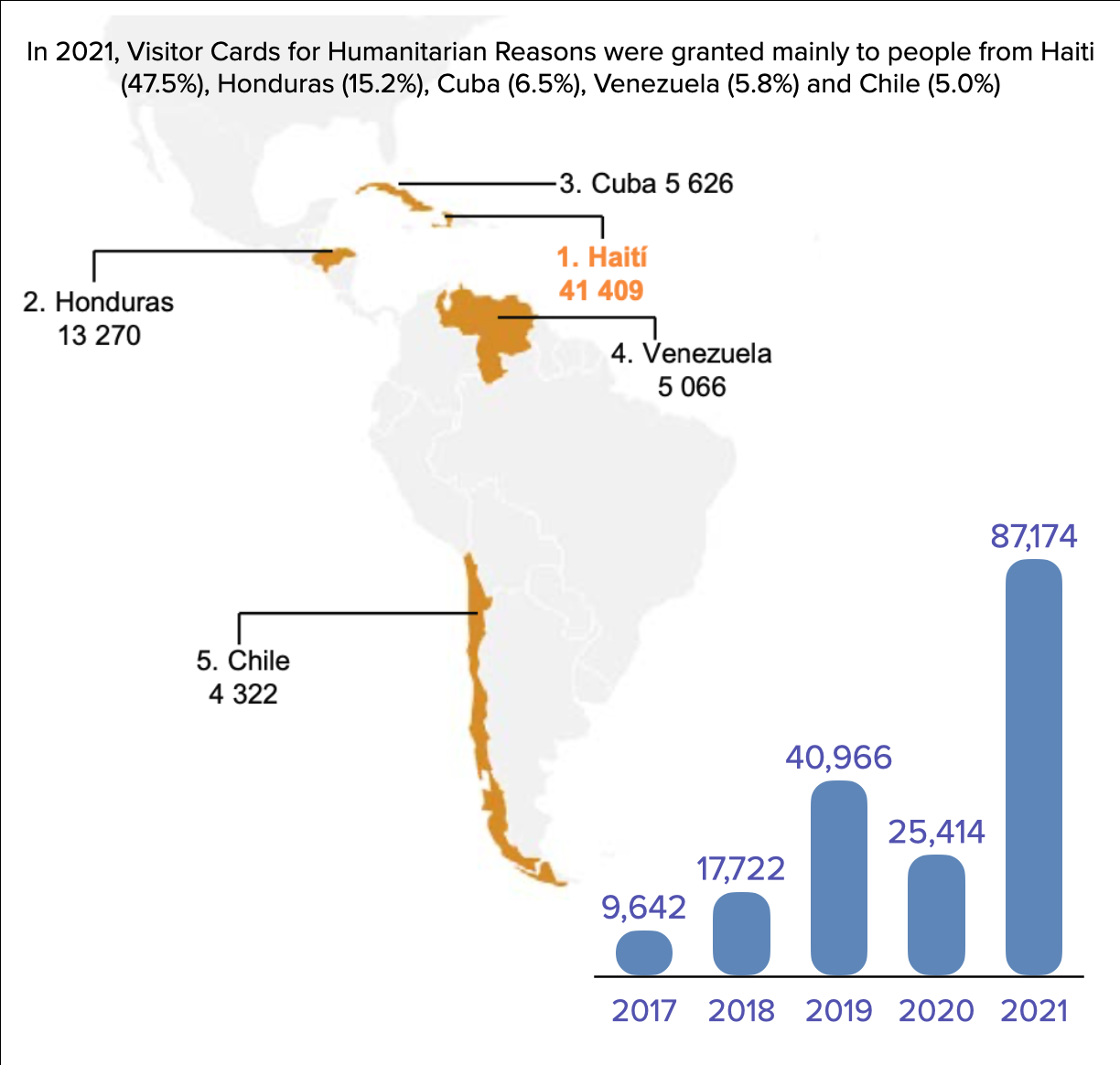

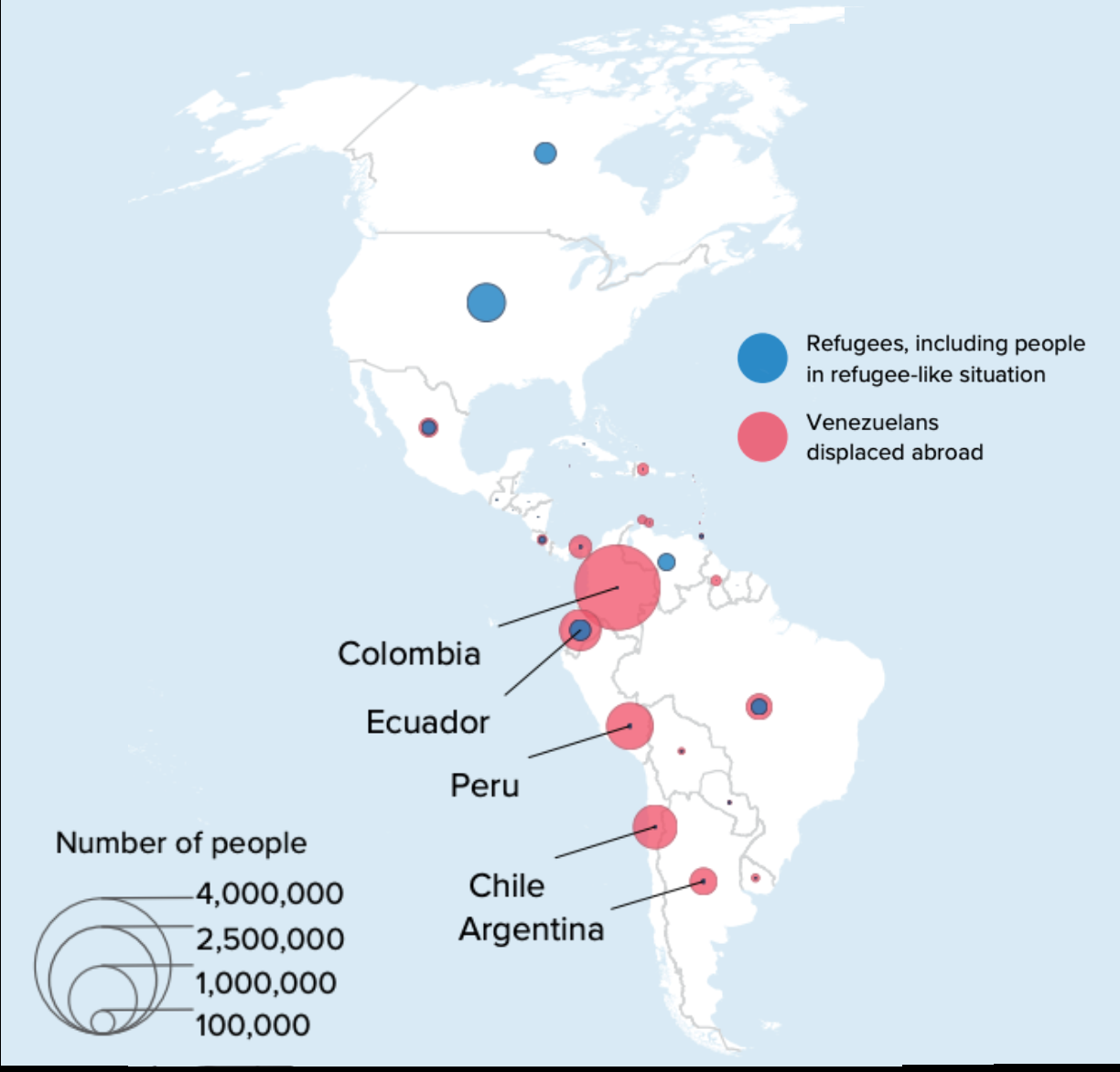

Although this information only tracks affirmative asylum cases or “sanctioned migration” it hints at major migration trends worldwide and in the region. To complement this information it is important to highlight certain specific events and countries to further dive into this topic.

Deep dive: Taxes and income justice

Introduction

Equality is a multidimensional concept and refers to equality of means (income and wealth), opportunities, capabilities and recognition (CEPAL, 2018). Here we will focus on income and wealth inequality.

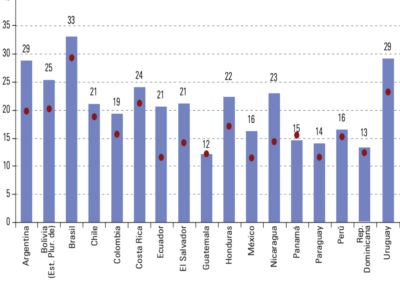

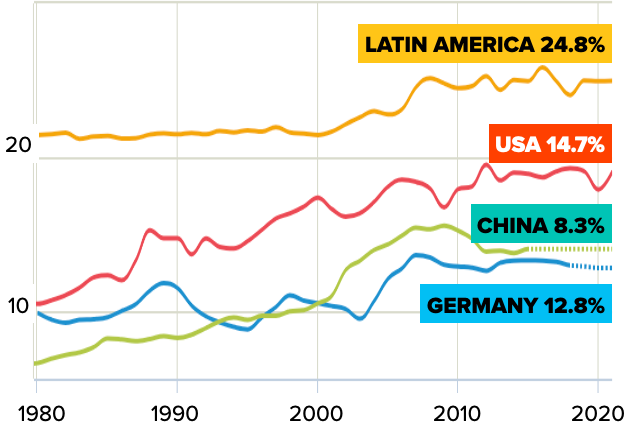

In Latin America the Gini coefficient for income inequality has fallen in recent decades, from an average of 0.53 in the early 2000s to an average of 0.46 in 2019. In turn, the concentration of income in the richest 1% increased from 22.6% in 1980 to 24.6% in 2019. The reason, income inequality has always been high.

Top 1% national income share. Historical (1980-2020)

Inequality is a historical and structural characteristic of Latin American and Caribbean societies, and has been maintained and reproduced even in periods of growth and economic prosperity. It is an obstacle to the eradication of poverty, sustainable development and the guarantee of people’s rights. It is based on a highly heterogeneous and poorly diversified productive matrix and on a culture of privilege that is a constitutive historical trait of the societies of the region (ECLAC, 2019).

The role of tax systems

Tax systems must become the pillar of financing for sustainable development (ECLAC, 2017). These play a fundamental role in reducing inequality directly, by providing the resources to finance public spending, public investment and social protection systems, and through progressive collection. However, the region is still far from developed countries in terms of tax collection and progressivity of the tax structure. As noted in ECLAC/Oxfam (2016), tax systems in Latin America have the following deficiencies:

- collection levels are low;

- tax regimes barely contribute to leveling income distribution;

- revenue from personal income tax is especially low;

- tax evasion reaches significant magnitudes, and

- effective tax rates on the highest incomes remain very low and their impact on income inequality is limited.

In 2000, the average tax burden in Latin America was 16.5%, while in 2018 it reached 20.8%. Argentina and Ecuador stand out for the greatest increases, with 9.0 percentage points of GDP, followed by Nicaragua (8.6% of GDP). At the other extreme are Panama, whose collection contracted 1.0 percentage point of GDP, and Guatemala, which practically maintained its tax burden. However, there is still a large collection gap compared to developed countries. Indeed, in 2018 the tax burden of the general government of the OECD countries reached an average of 33.9%, that is, 13.1% more than the average for Latin America.

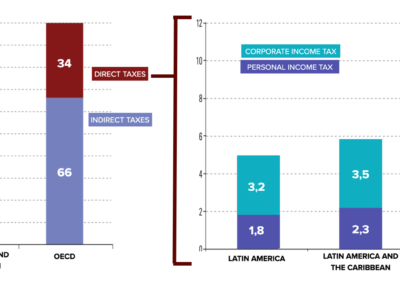

In terms of the tax structure, in Latin America the collection comes mainly from consumption taxes, which represent 46.2% of total income, followed by income tax, with 26.8% of the total, and contributions to social security, with 20.5% of the total. In the OECD, income tax, which reaches 34.0% of the total, and social security contributions, which represent 26.6% of the total, have a greater relative weight, while consumption taxes reach to 32.3% of the total.

The main differences between Latin America and the OECD, with regard to the tax burden, occur in what is called direct taxation. In the region, income tax collection reaches an average of 5.6% of GDP, while in the OECD the average is 11.5% of GDP; that is, there is a difference of 5.9 percentage points of GDP. In turn, for social security contributions, the region collects the equivalent of 4.3% of GDP, while in the OECD these taxes represent 9.0% of GDP, so there is a difference of 4.7 percentage points of GDP.

The challenge of increasing tax collection

The effectiveness of new tax measures is limited by shallow tax bases, unwieldy tax systems and weak administrative infrastructures. Although implementation will vary considerably across Latin America, The Economist Intelligence Unit expects governments to:

- Levy new direct taxes on high-income individuals.

- Improve corporate tax collection with business formalization or even corporate tax hikes.

- New indirect taxes, particularly on digital services.

Total tax and contribution rate payable by businesses in 2019

Although businesses are a prime target for higher taxes it is never an easy task. It is important to consider that this may trigger capital flight, that corporate taxes are already high and that the universe of corporate tax payers is relatively small.

“According to the Tax Foundation, a US-based think-tank, when weighted by GDP, LAC has the highest average statutory corporate tax rate (of slightly over 30%) of any region in the world. Moreover, the statutory rate is in itself not representative of the legal tax burden faced by companies. In fact, when focusing on the “total tax and contribution rate”, which includes mandatory contributions payable by businesses, the picture is even grimmer. The high rates of taxation are at least partly driven by high levels of informality. The universe of corporate taxpayers in LAC is relatively small, which means that companies that do pay taxes bear high corporate tax rates by global comparison. Some governments will choose to tackle this problem head-on, by simplifying procedures to register businesses, creating special tax regimes for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and increasing inspections of subcontracting processes.“ Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit “Higher taxes to boost fiscal accounts in Latin America”

The Net Wealth Tax proposition

The idea of taxing the assets of natural persons is gaining strength in the world. In addition to the unequal distribution of income and wealth, studies show that income taxes are regressive at the top, that is, the top 1% pay lower average tax rates than the middle class, so they do not help mitigate this concentration.

One of the instruments under consideration is the net wealth tax, which is part of the so-called property taxes. This type of tax is normally applied annually, and its taxable base is made up of the difference between the value of all the assets and rights that the person owns (assets) and the value of the debts that they maintain (liabilities). As it is a direct tax, it is feasible, and common, to give it a progressive design, with an exempt section up to a certain limit of net worth and then a scale of increasing marginal rates.

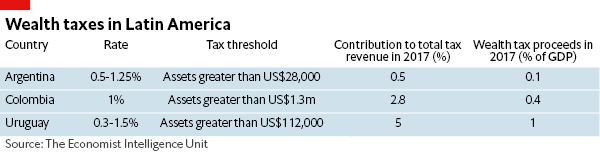

Currently, the use of this tax in the region is scarce. It is only applied in Argentina (tax on personal assets), Colombia (tax on wealth) and Uruguay (tax on wealth). Globally, there has been a decline in the use of wealth taxes in recent decades, particularly in developed countries.

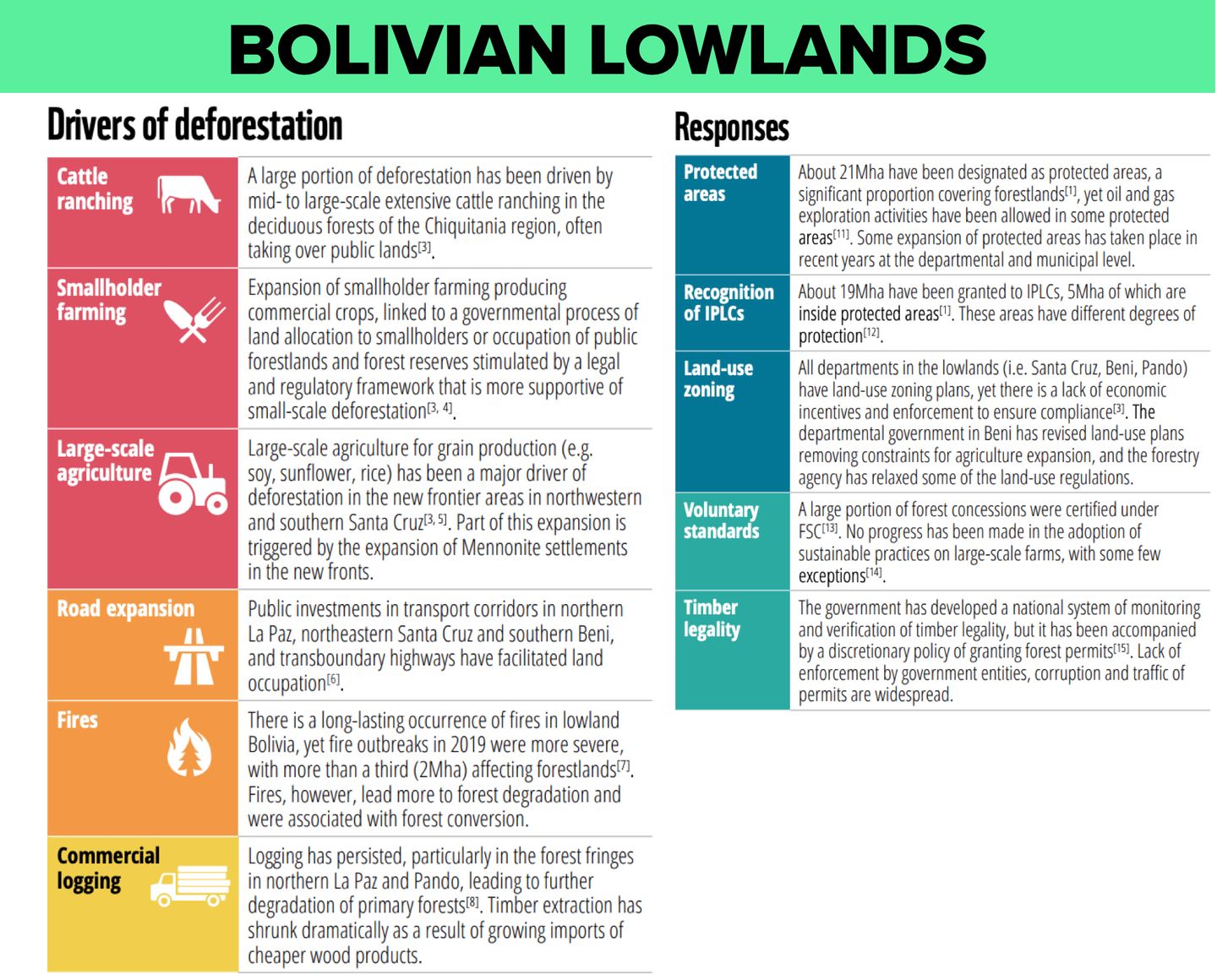

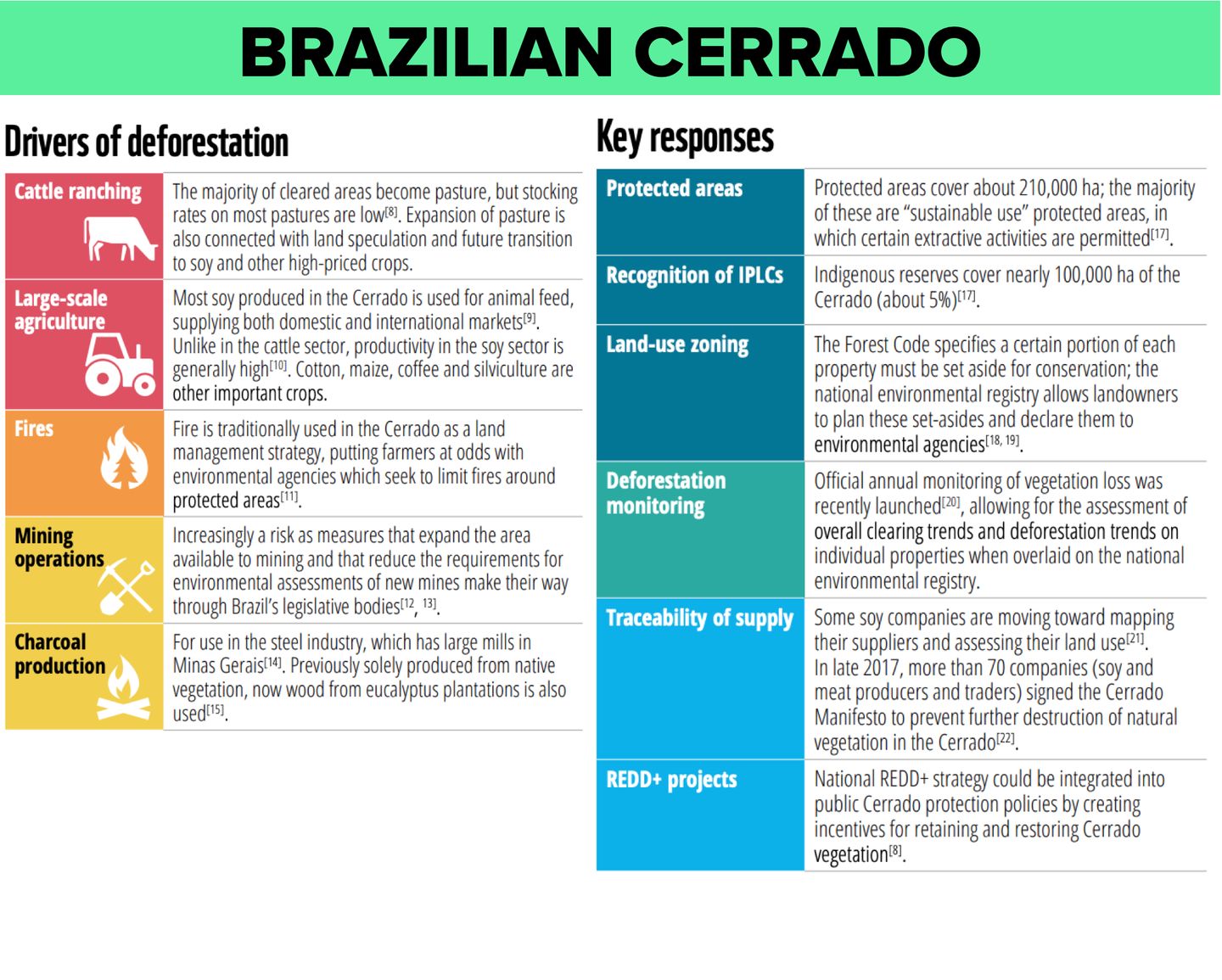

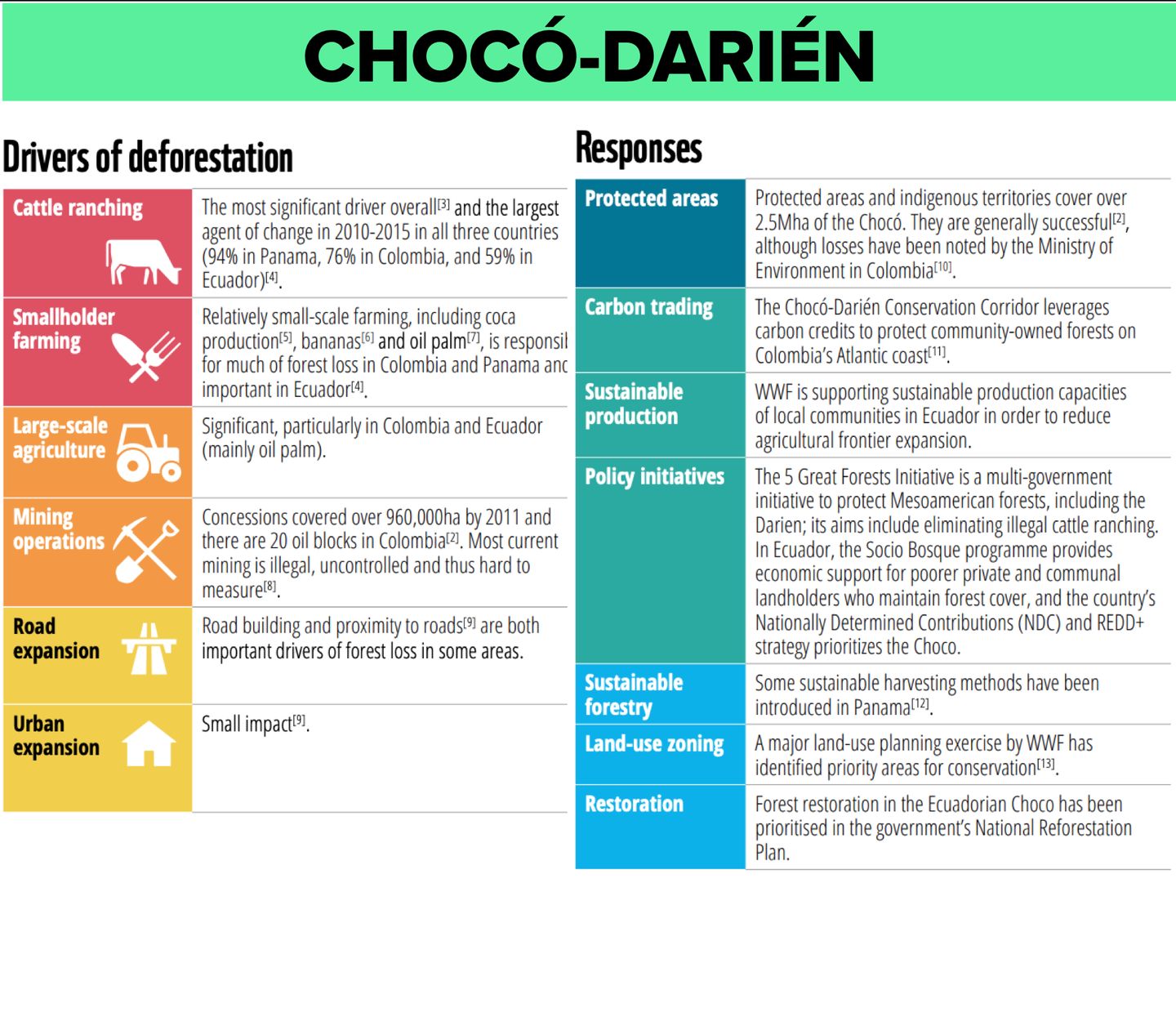

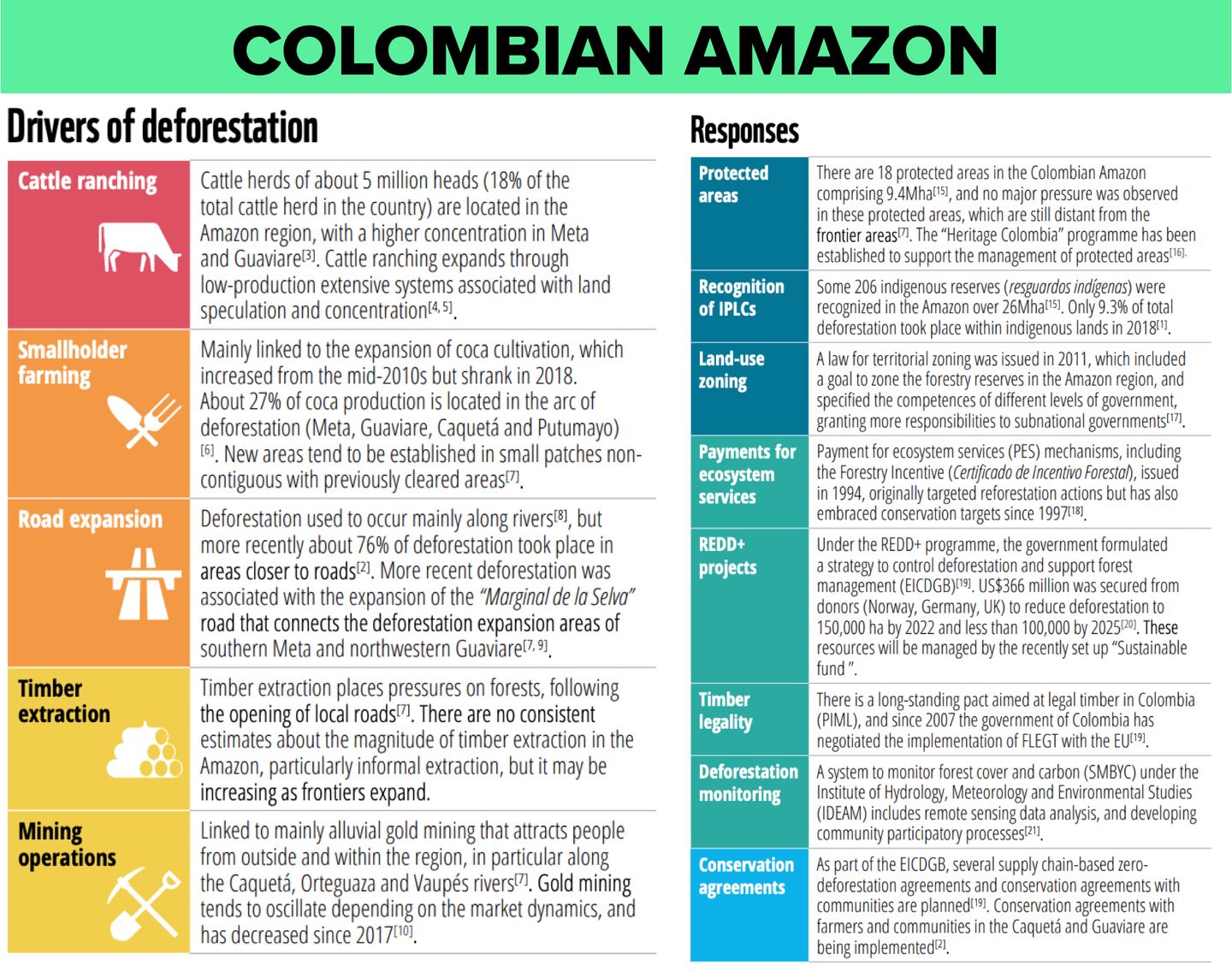

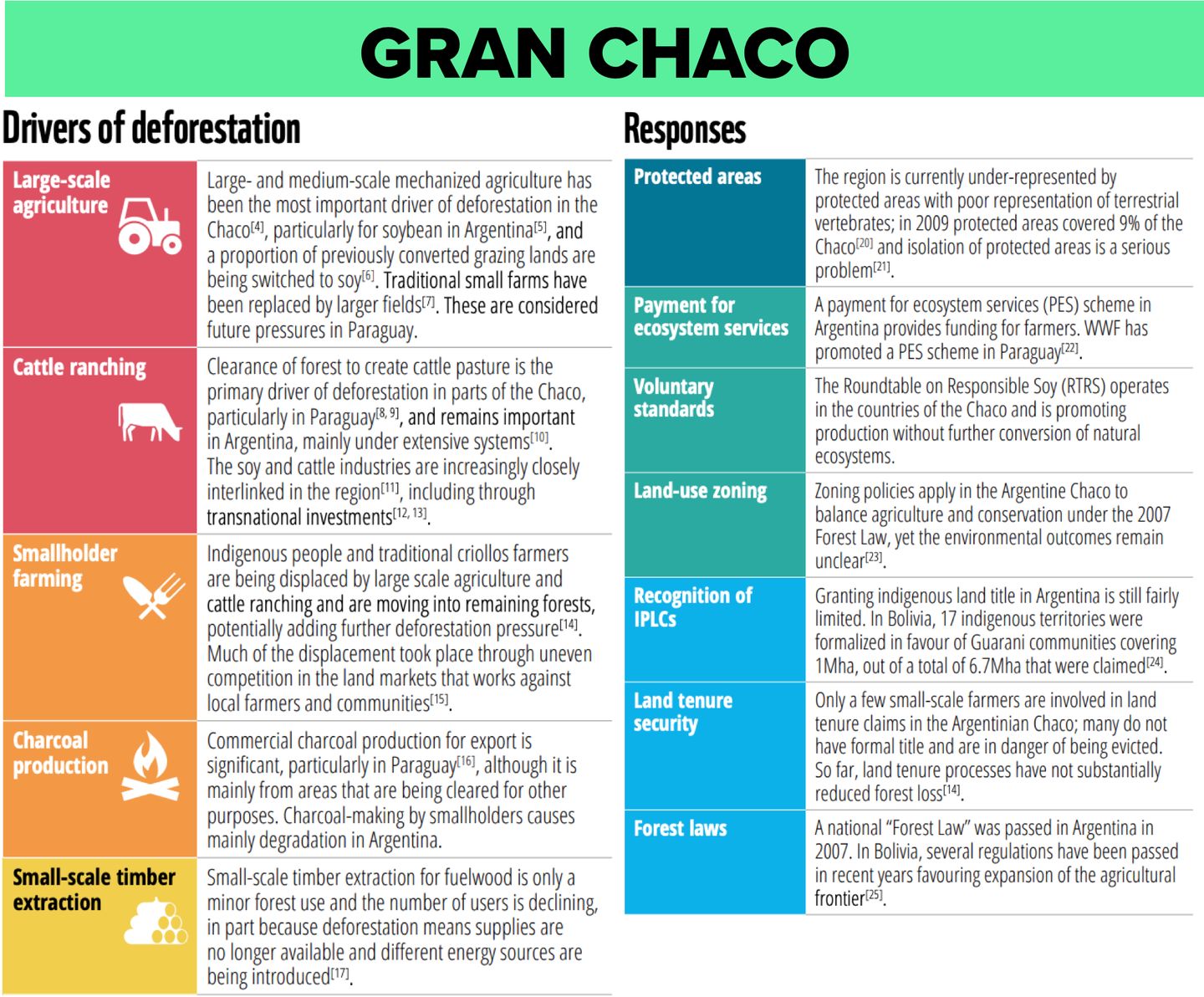

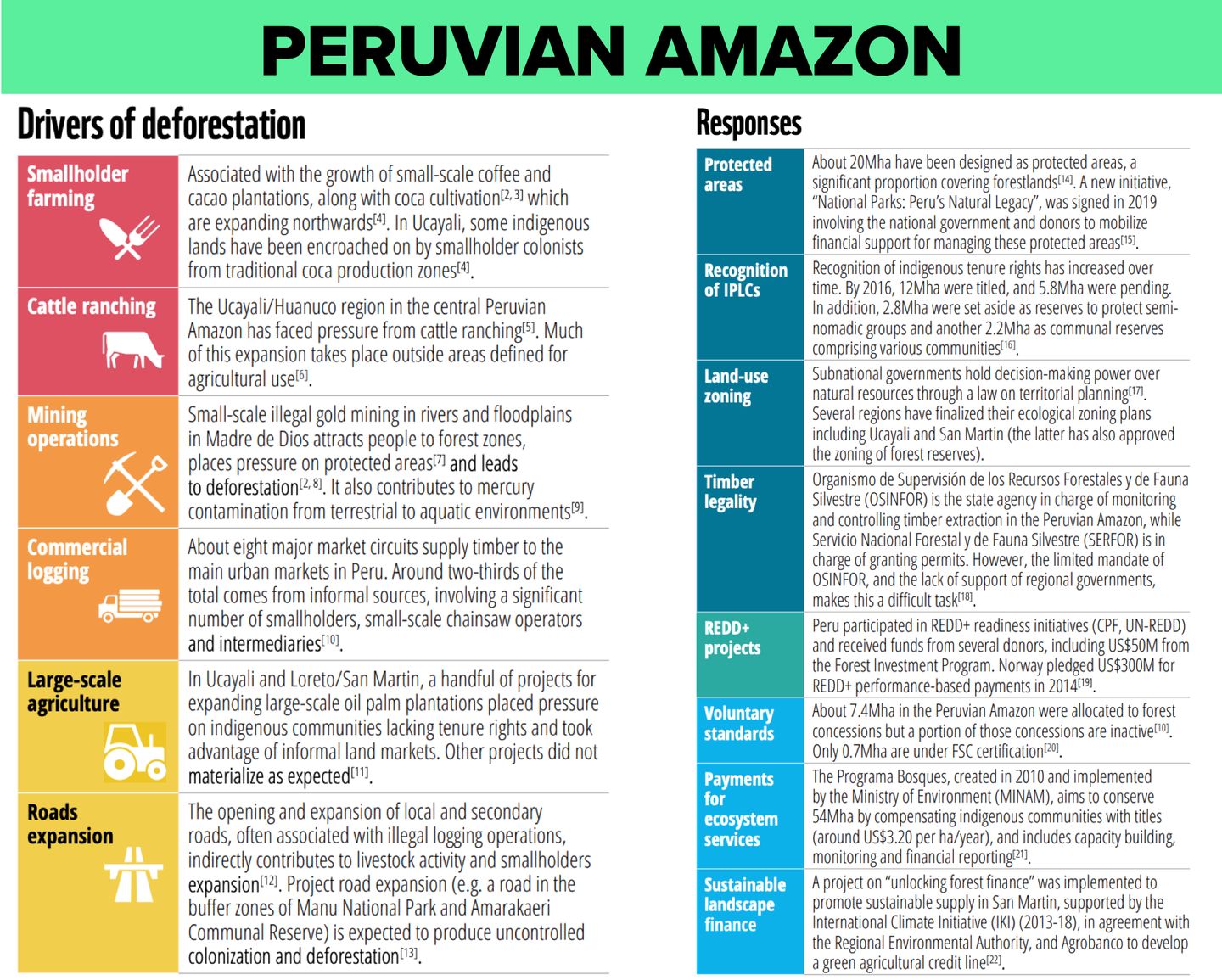

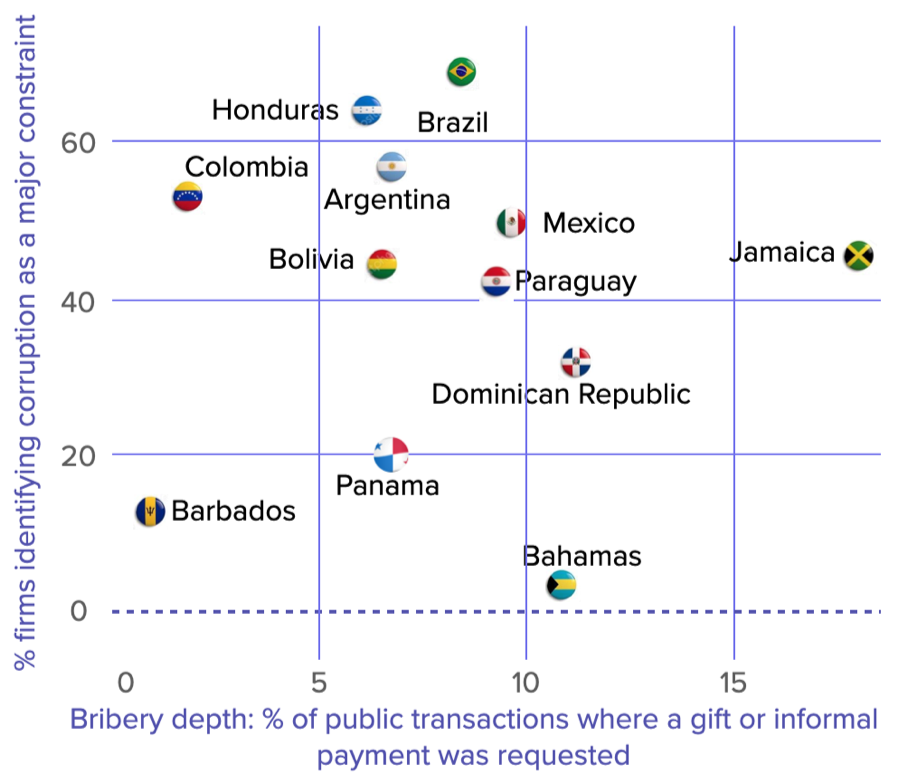

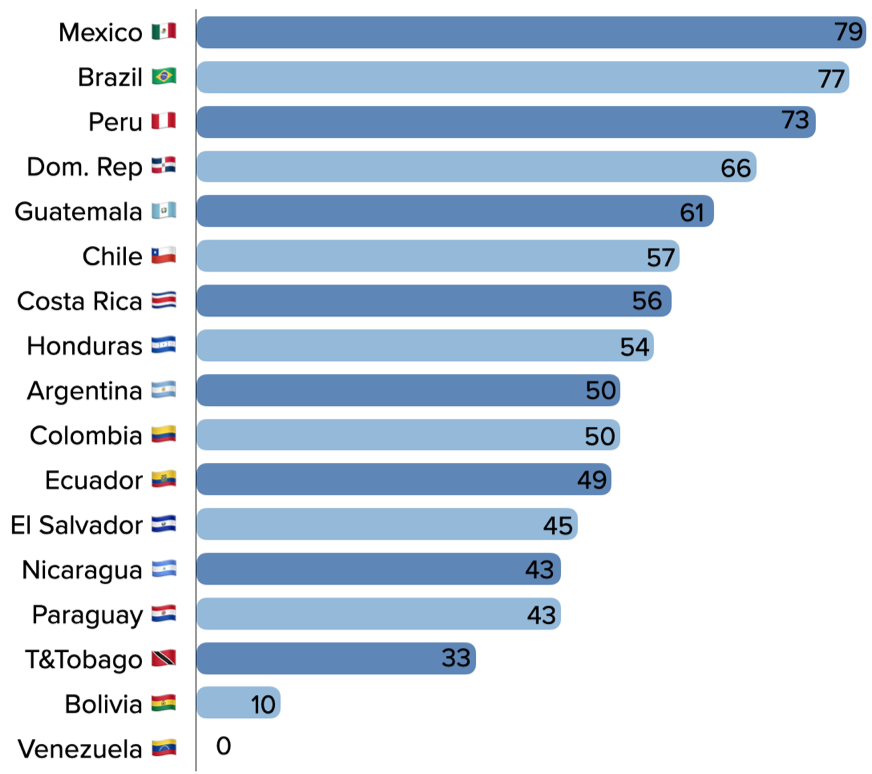

Deforestation hotspots

Change signals

Curated trends, signals or opportunities

Prêmio Megafone Ativismo

The award intends to contribute to increase the visibility of activism actions, promoting the practice of activism as a catalyst for social transformation and the emergence of new agents of activism, mainly young people and women, in debate and in the action of combating the climate crisis and related causes.

It is a realization of the coalition of organizations that include Pimp My Carroça, Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), WWF, Greenpeace Brasil, Engajamundo, Hivos e Vozes Pela Ação Climática Justiça (VAC).

Collective and shared mandates

The “collective and shared mandates” are a way of exercise of a legislative mandate in which the elected representative pledges to share power with a group of citizens. It is the application to the policy of sharing logic, already present in different spheres of economy and society. While in a traditional mandate, the legislator is free to exercise it according to their interests, conscience and within the parameters of the party in collective and shared mandates, the legislator allows a group of people to help him define her political positions in relation to matters that are being discussed and voted on in parliaments.

Source: Skoll Foundation: MapBiomas (2022). Foto ACV Brasil

Change signals

Initiative spotlight

Rizoma Agro

A regenerative agricultural practice

Rizoma Agro is a Brazilian agroforestry company that focuses on sustainable production of timber, fruits, and other crops. Founded in 2010, Rizoma Agro has become a leading voice in the movement towards sustainable agriculture and forestry practices in Brazil. The company operates in the Brazilian Amazon region and aims to promote reforestation, agroforestry, and the conservation of native forests. Rizoma Agro’s main product is Brazilian teak, a high-value hardwood used in the production of furniture, flooring, and other wood products. However, the company also produces a variety of other crops, including cocoa, açaí, and cupuaçu.

A regenerative agricultural practice

Agroforestry is a land management system that integrates trees with crops and/or livestock, creating a more sustainable and diverse agricultural system. Agroforestry systems can provide a range of environmental and economic benefits, including soil conservation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and increased food security. In agroforestry systems, trees and crops are planted together, allowing for complementary interactions between different species. For example, trees can provide shade for crops, protect soil from erosion, and improve soil fertility by fixing nitrogen. In turn, crops can provide additional income streams for farmers and help to maintain the health of the agroforestry system.

Agroforestry is important to address global warming because it can help sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Trees are a natural carbon sink, meaning they absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and store it in their biomass and in the soil. By combining trees and crops or animals, agroforestry systems can increase carbon sequestration potential while also providing multiple benefits to farmers and the environment. Additionally, agroforestry can reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, which are often energy-intensive and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Scale of agroforestry in Brazil and its challenges

Despite the potential benefits of agroforestry, its scale in Brazil is still relatively small. Compared to the 263 million hectares under farming systems (2020), which represents approximately 30% of the national territory, agroforestry in Brazil covers around 5% of the farmed land, and there is no information if these agroforests follow the conventional model or are oriented by agroecological principles.

Despite the benefits of agroforestry, the expansion of agroforestry systems in Brazil and Latin America faces several challenges. The main barriers to the adoption of agroforestry at scale in Brazil includes the lack of technical assistance, limited access to finance, regulatory barriers, land tenure issues, and limited market access. Many farmers lack the technical knowledge and support needed to establish and maintain agroforestry systems, while financing options for such projects are often limited. The legal framework for agroforestry in Brazil is complex and can be a barrier to adoption, while land tenure issues and limited market access can make it difficult for farmers to invest in agroforestry systems or find buyers for their products. Additionally, the high upfront costs of establishing agroforestry systems can be a barrier for smallholder farmers, who may lack the resources to invest in long-term land management practices.

Sources: World Agroforestry, 2023. How agroforestry can restore degraded lands and provide income in the Amazon, Mongabay 2023. Schuler, H.R.; Alarcon, G.G.; Joner, F.; dos Santos, K.L.; Siminski, A.; Siddique, I. Ecosystem Services from Ecological Agroforestry in Brazil: A Systematic Map of Scientific Evidence. Land 2022, 11, 83. Farming Destroyed Brazil’s Rain Forests. It Could Also Save Them, Time 2023. Fotos: Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2023 and Mongabay 2023.

2022 REPORT