2022 report

Change & Emergence

in Latin America

Planetary Health

Current Situation

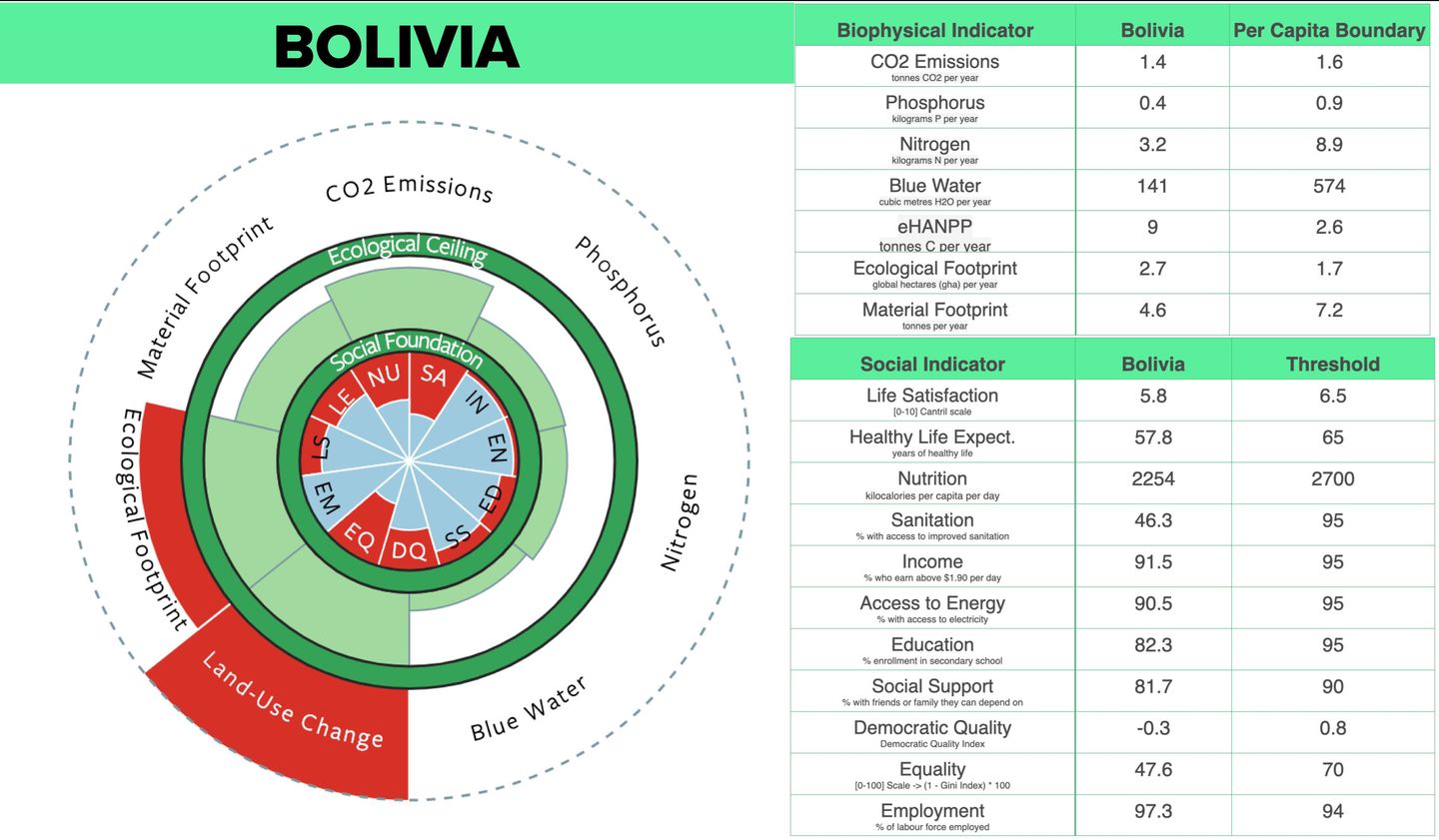

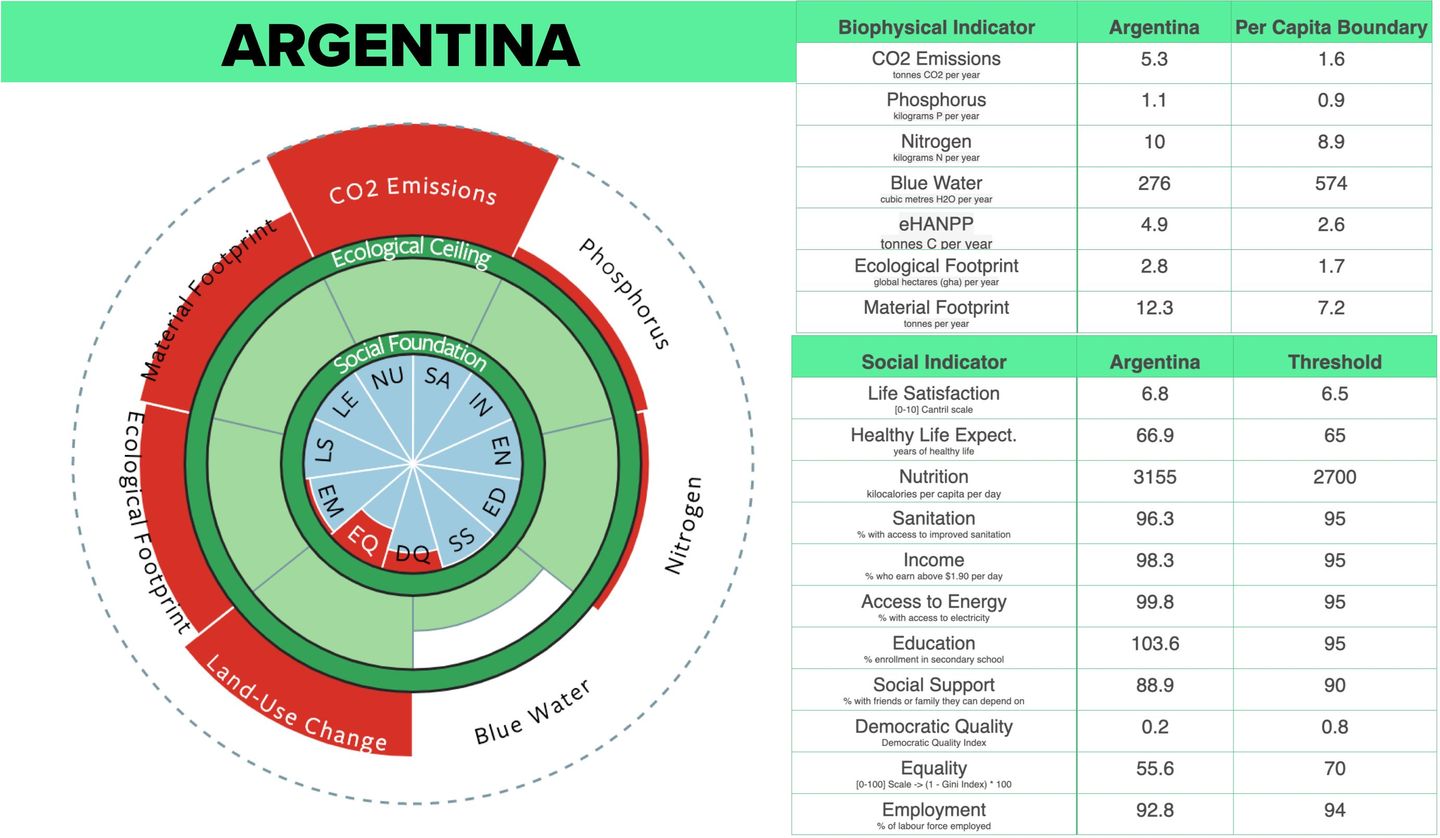

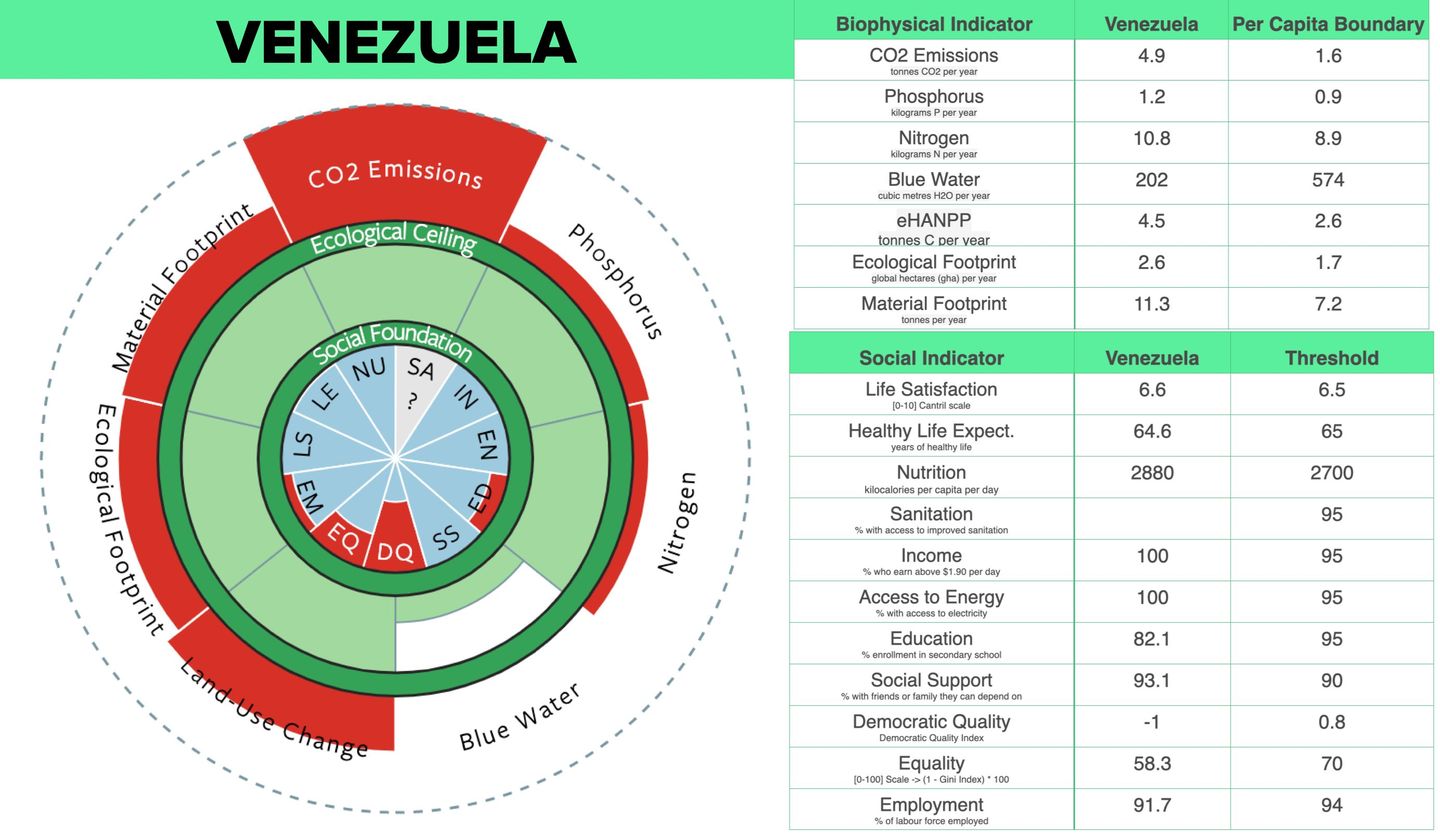

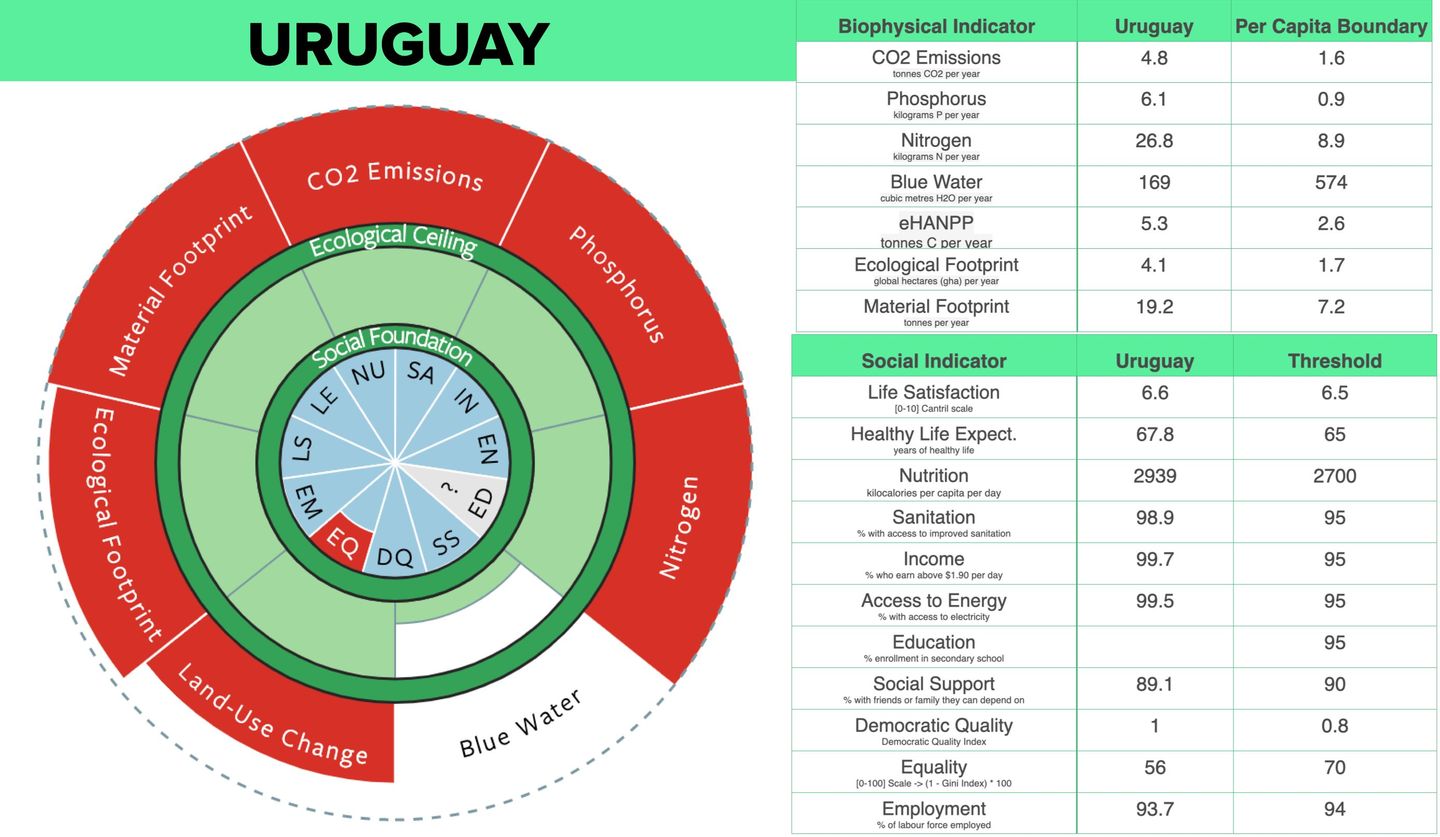

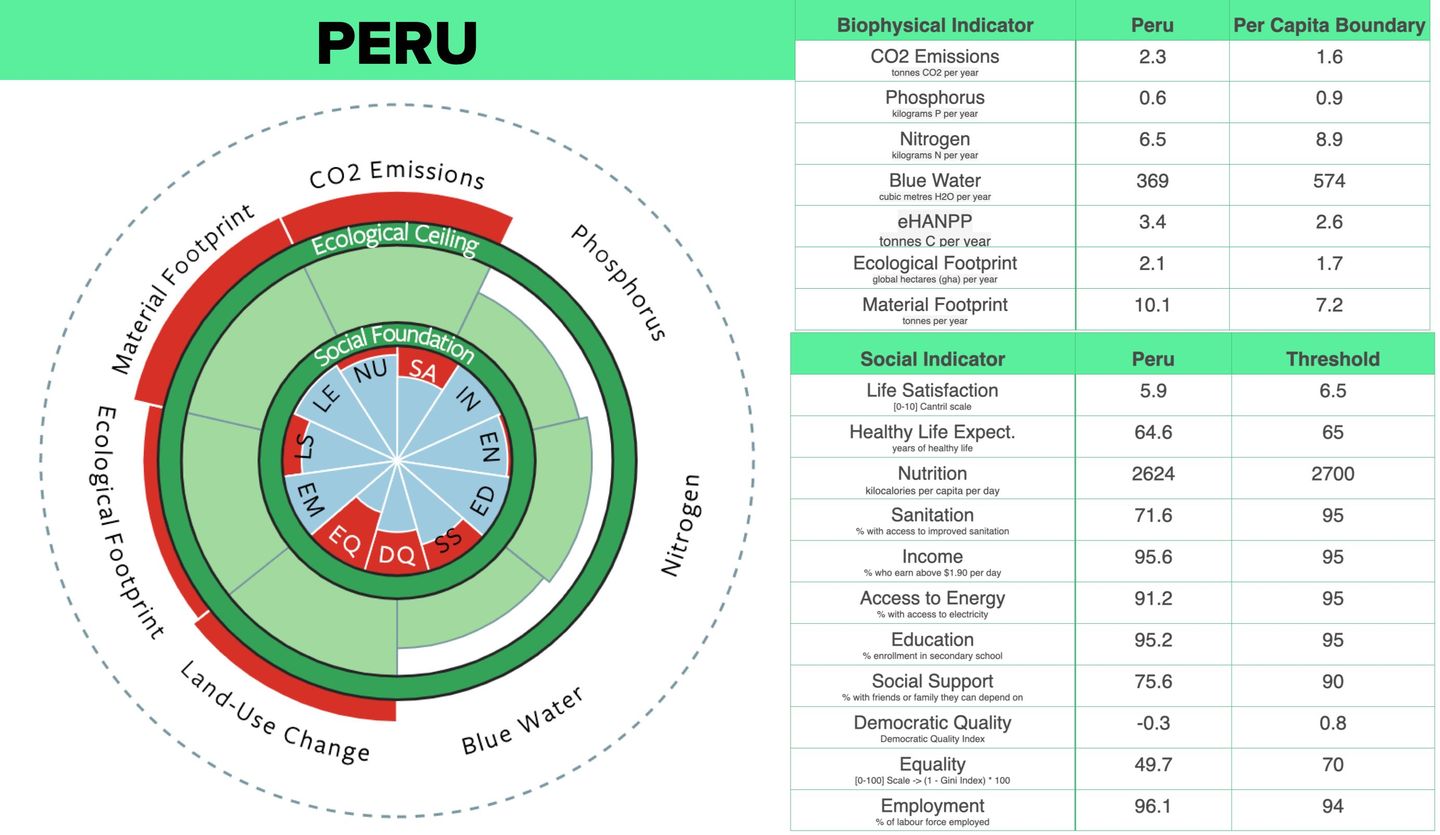

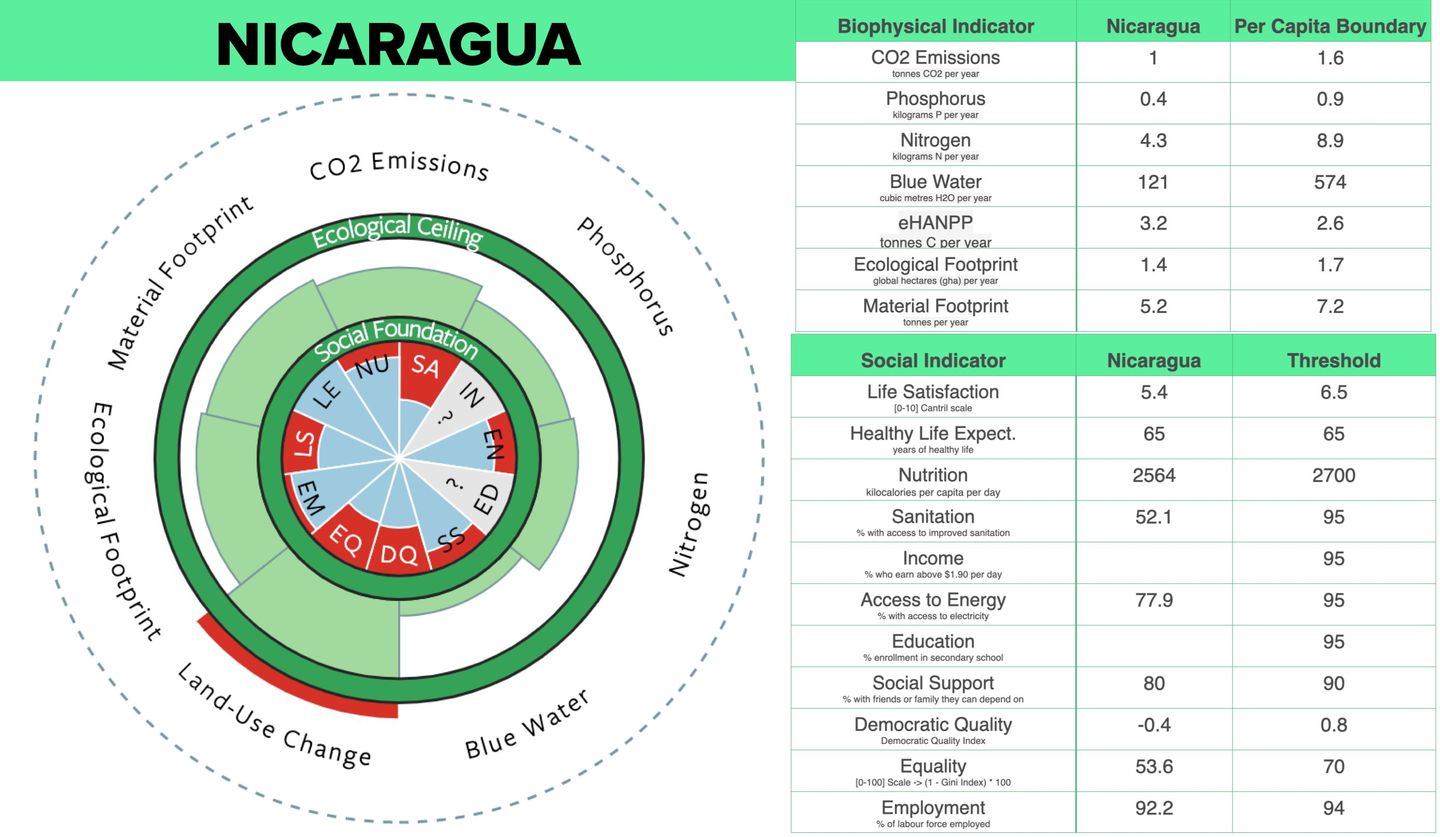

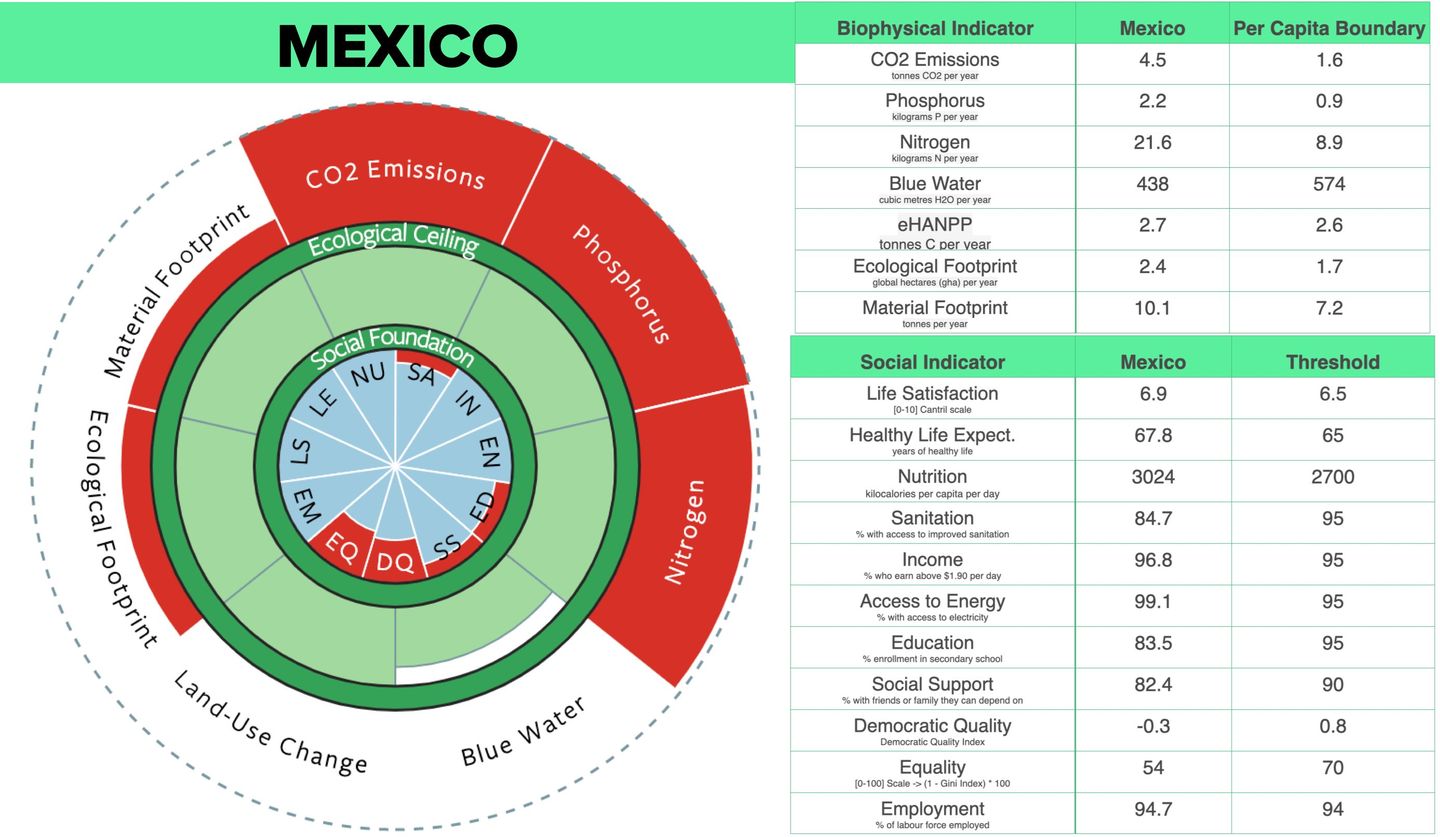

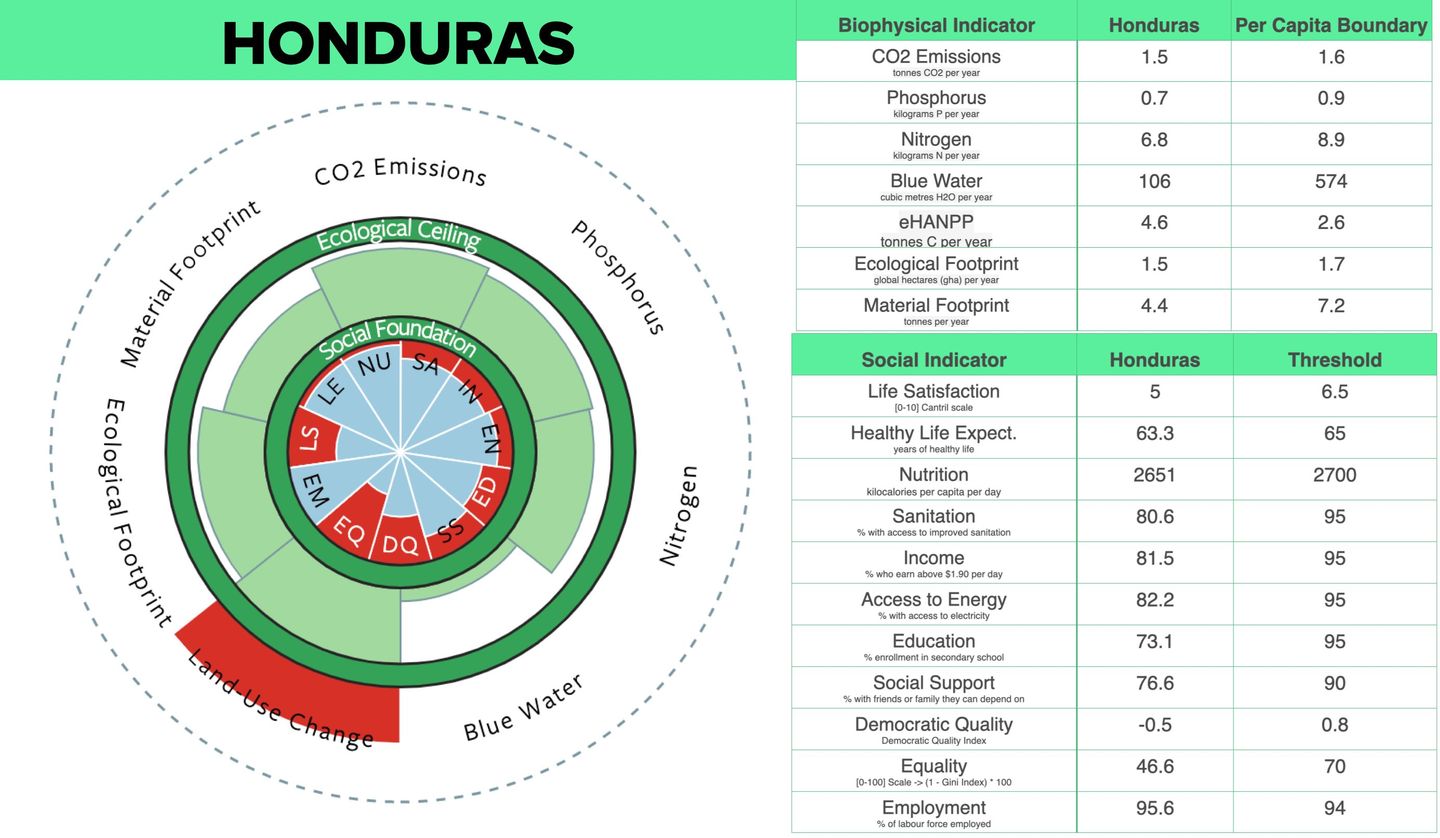

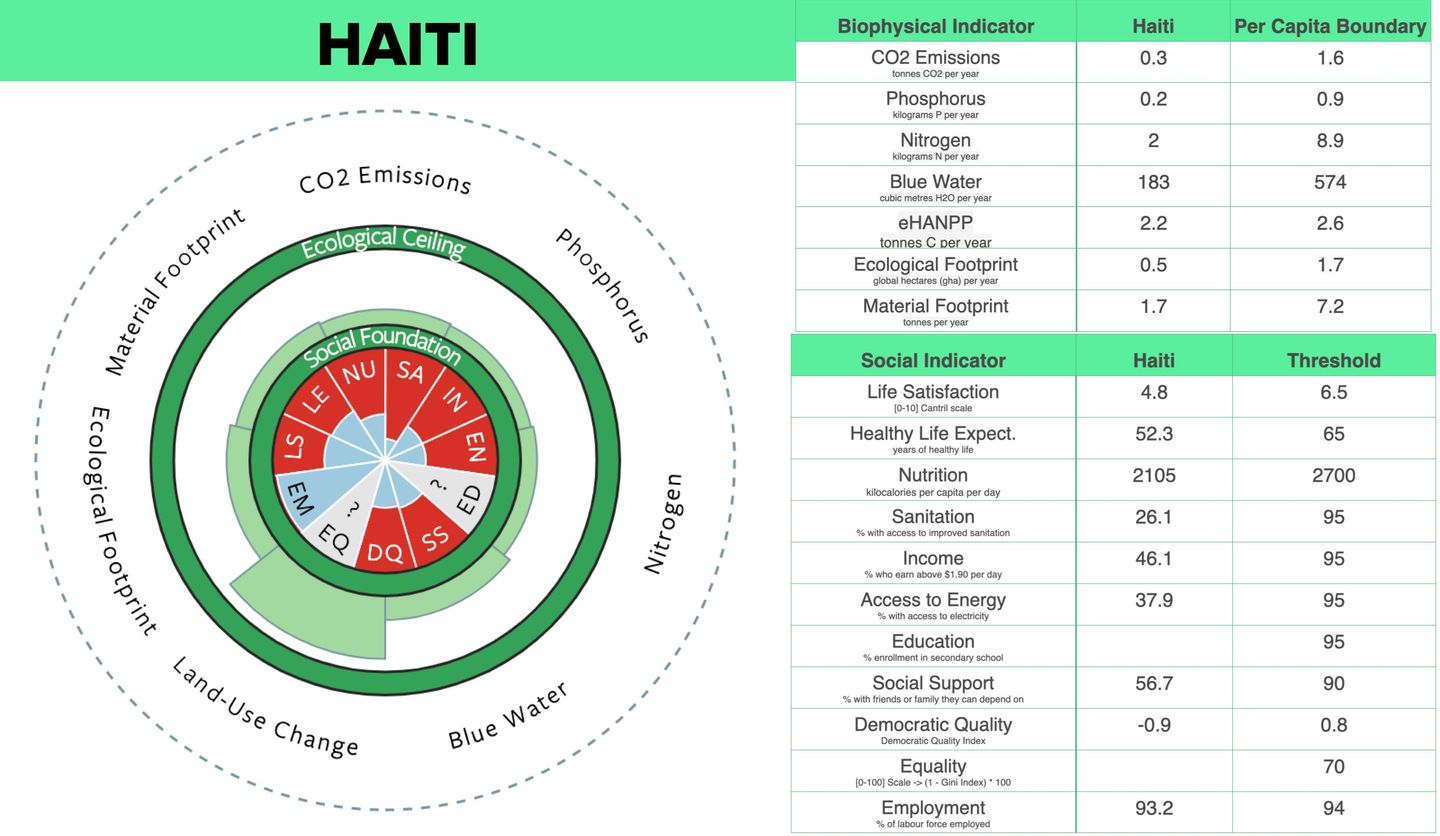

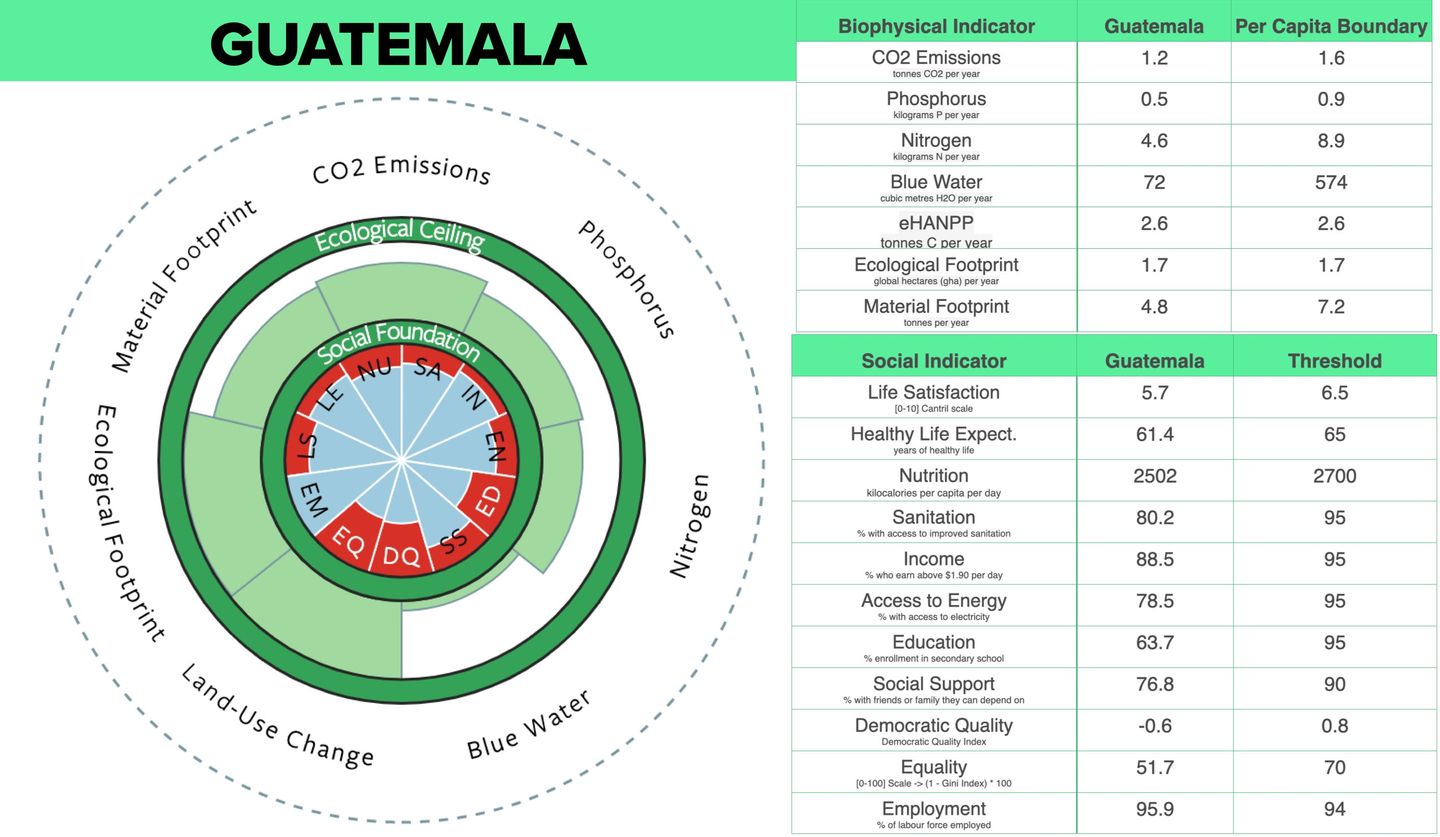

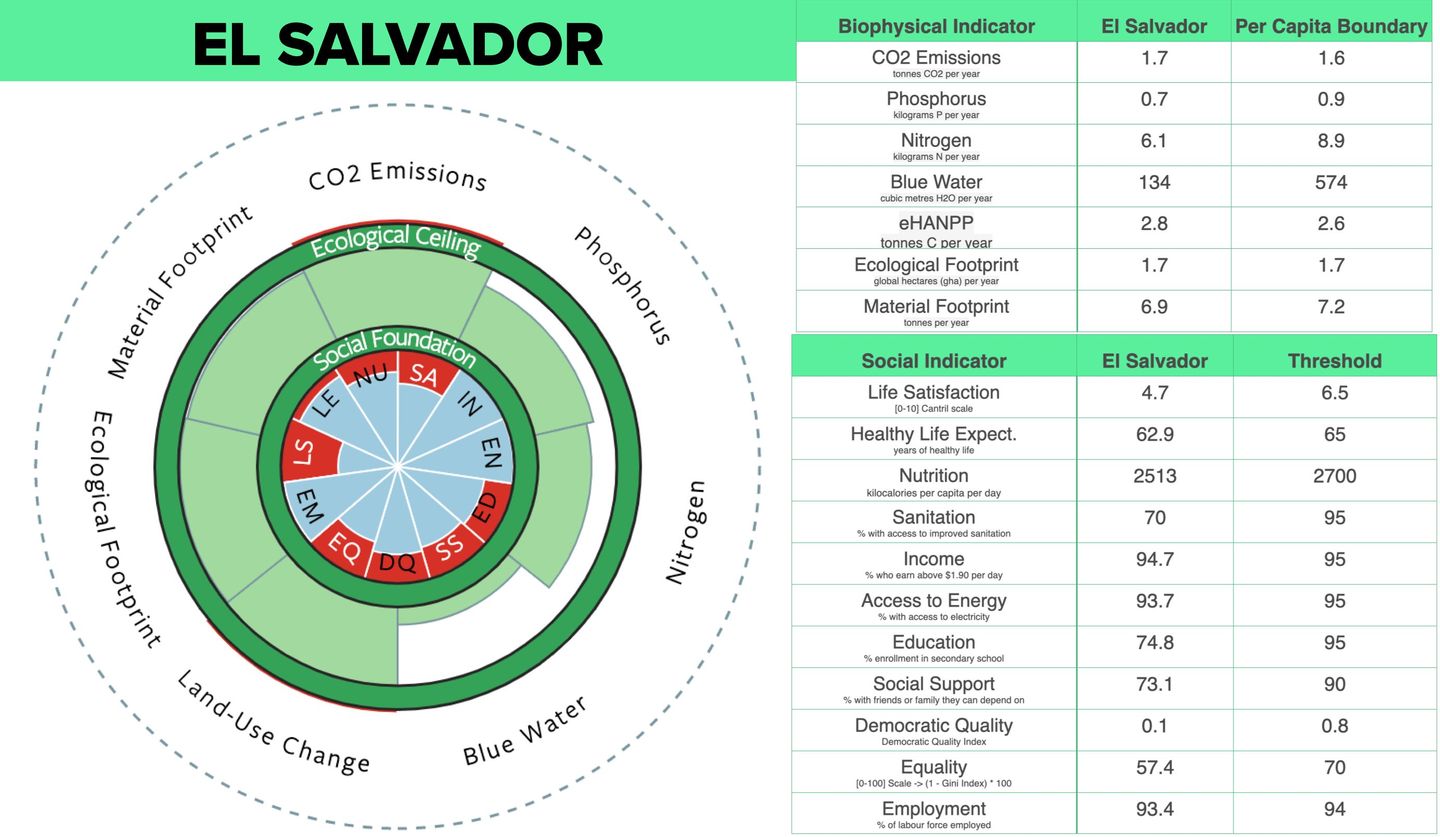

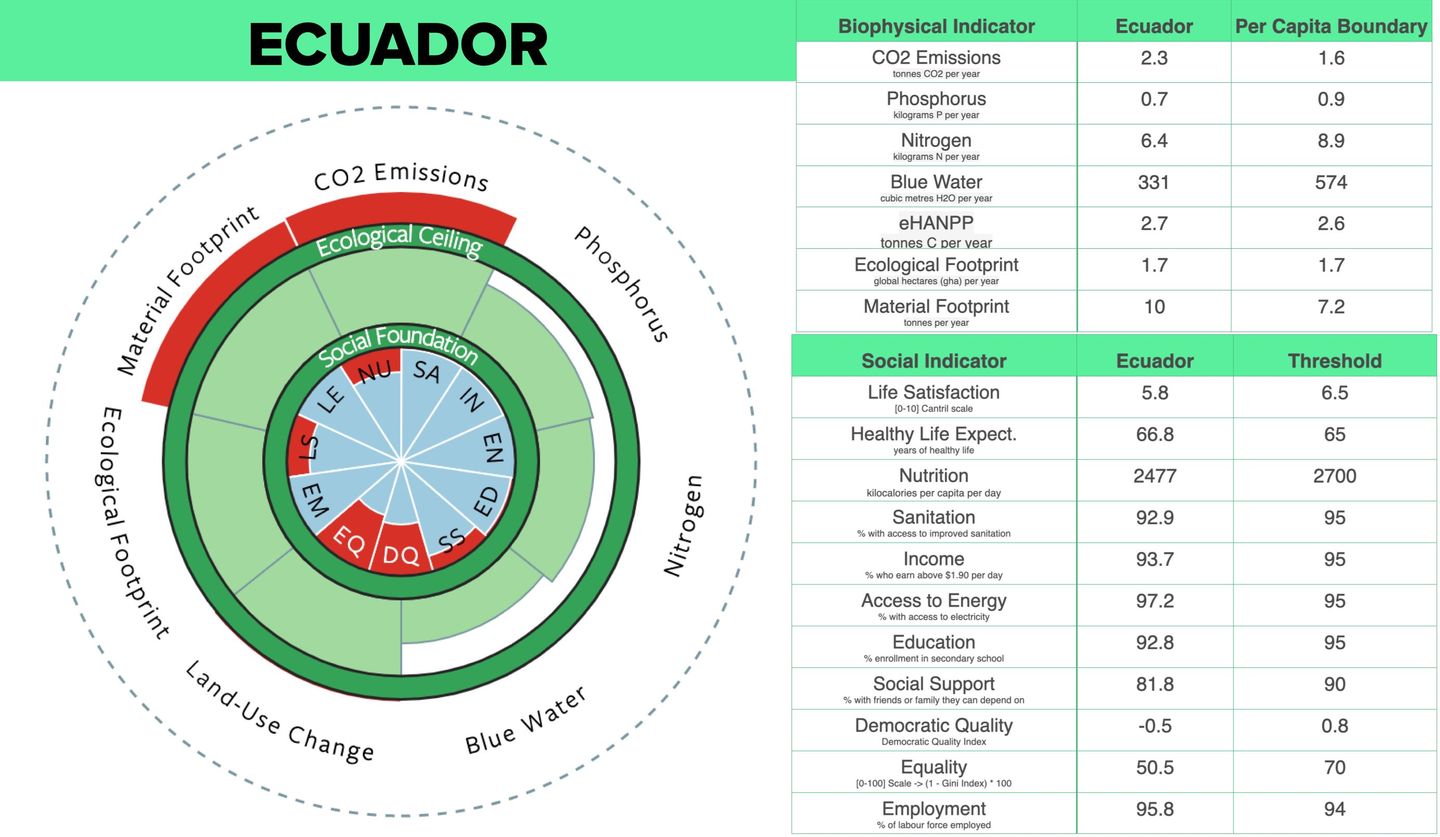

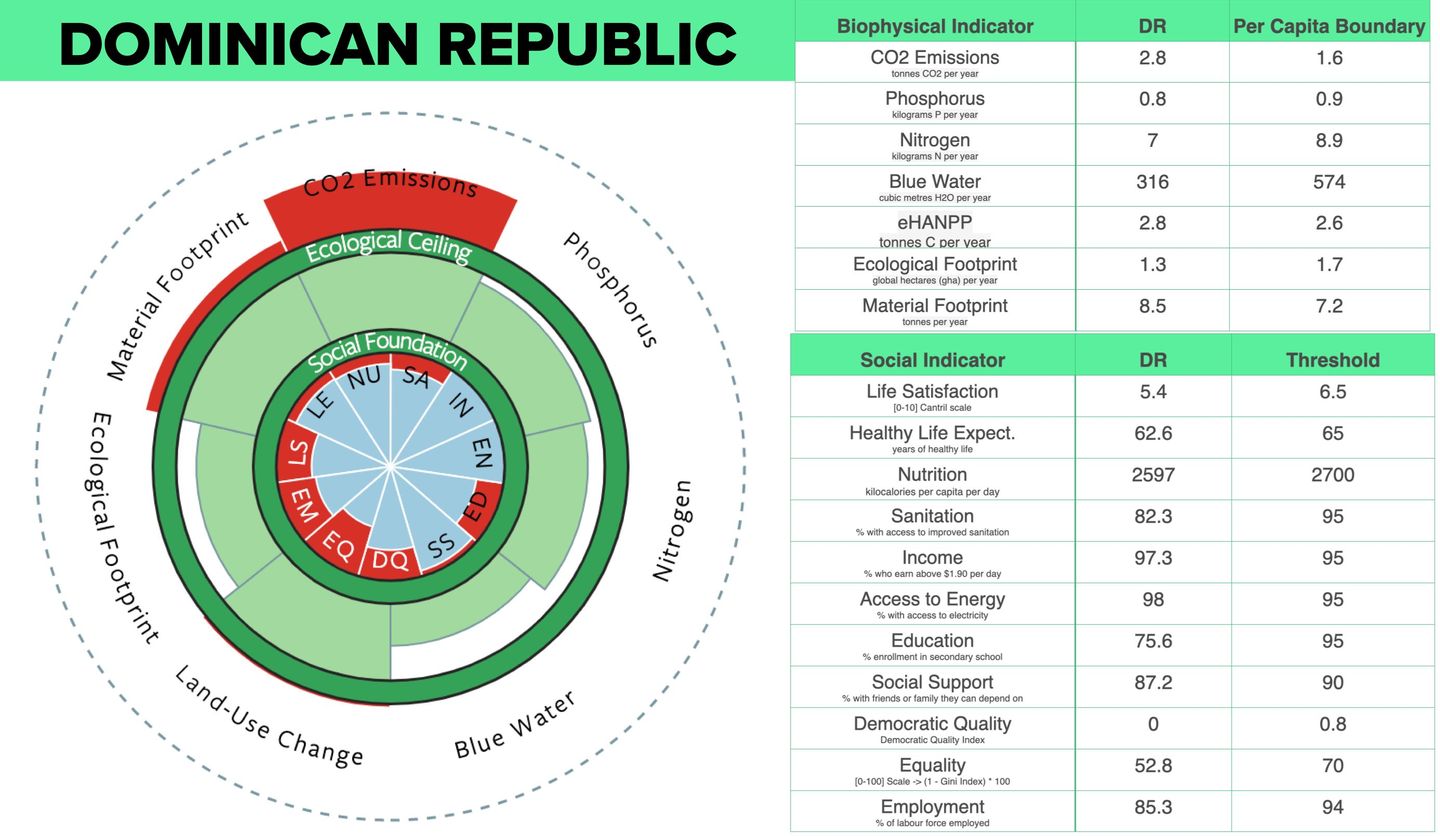

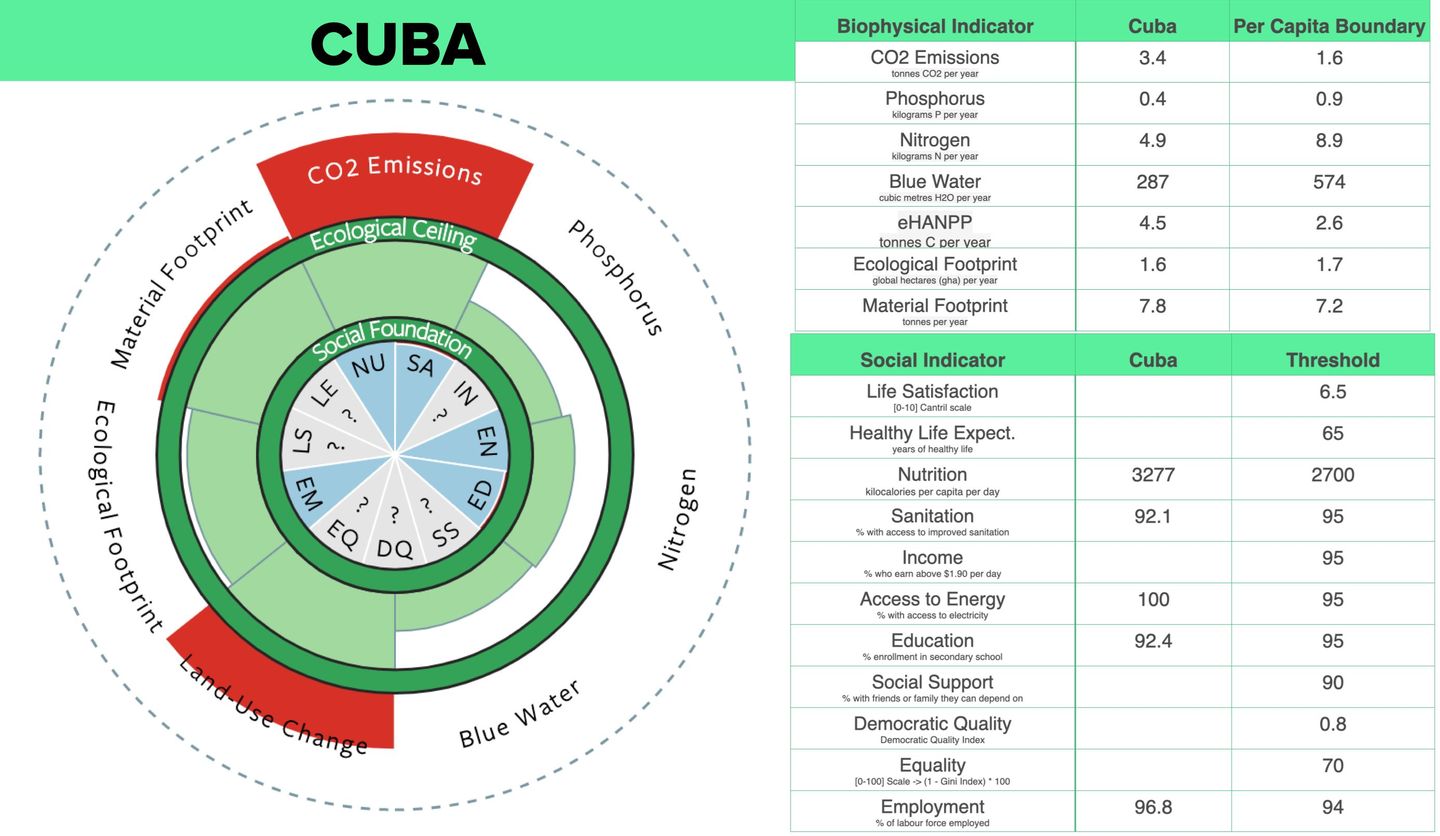

Selected planetary health indicators

A. Lorem Ipsum

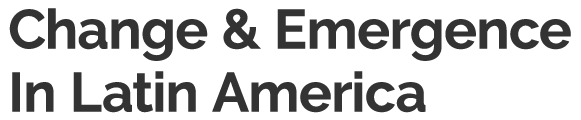

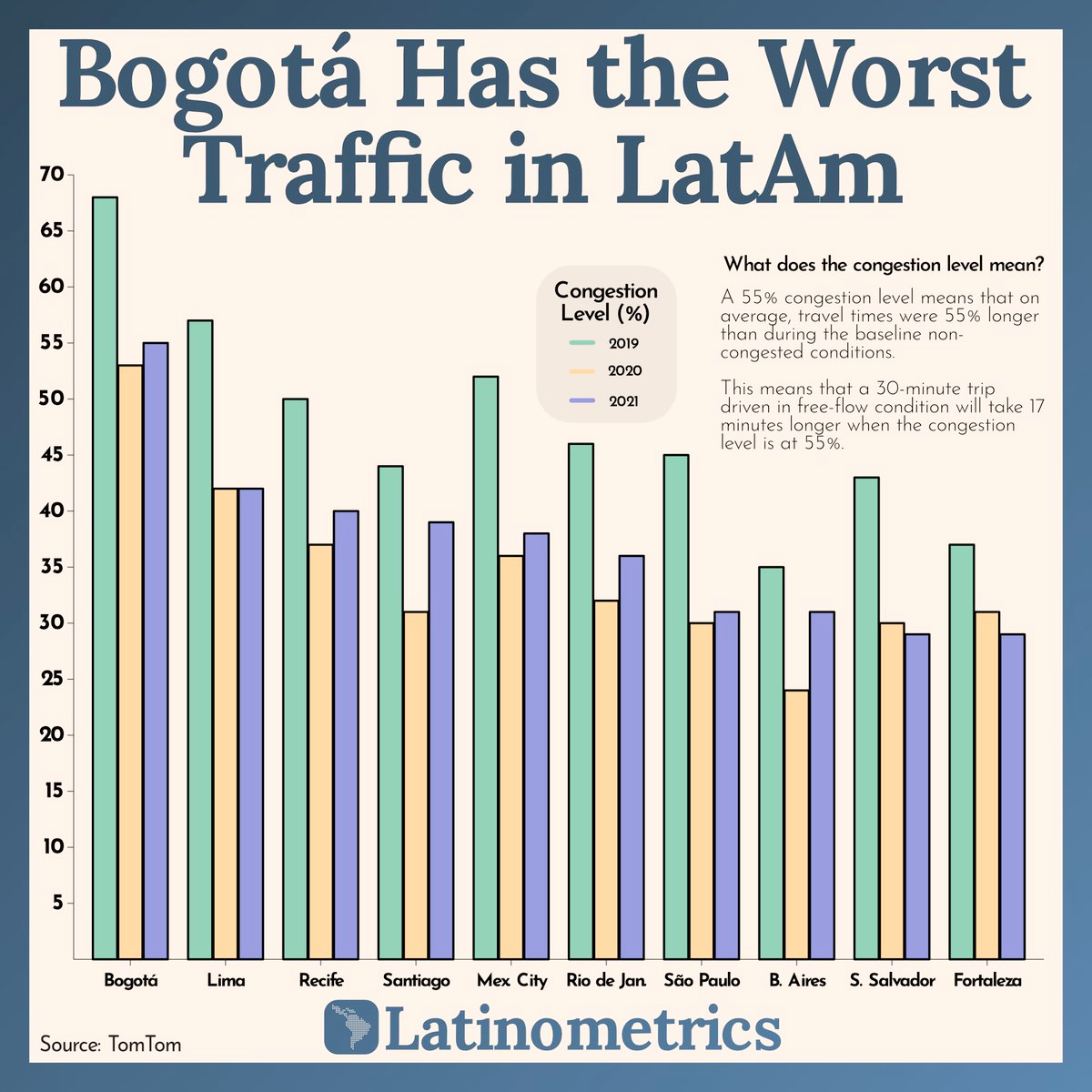

Cities will be a major hotspot for addressing global warming and Latin America’s urbanization is more than 30 years ahead of the world’s average.

- Estimates say that by 2050, 90% of Latin Americans will be urban dwellers.

B. Lorem Ipsum

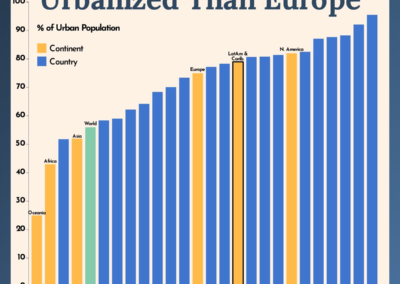

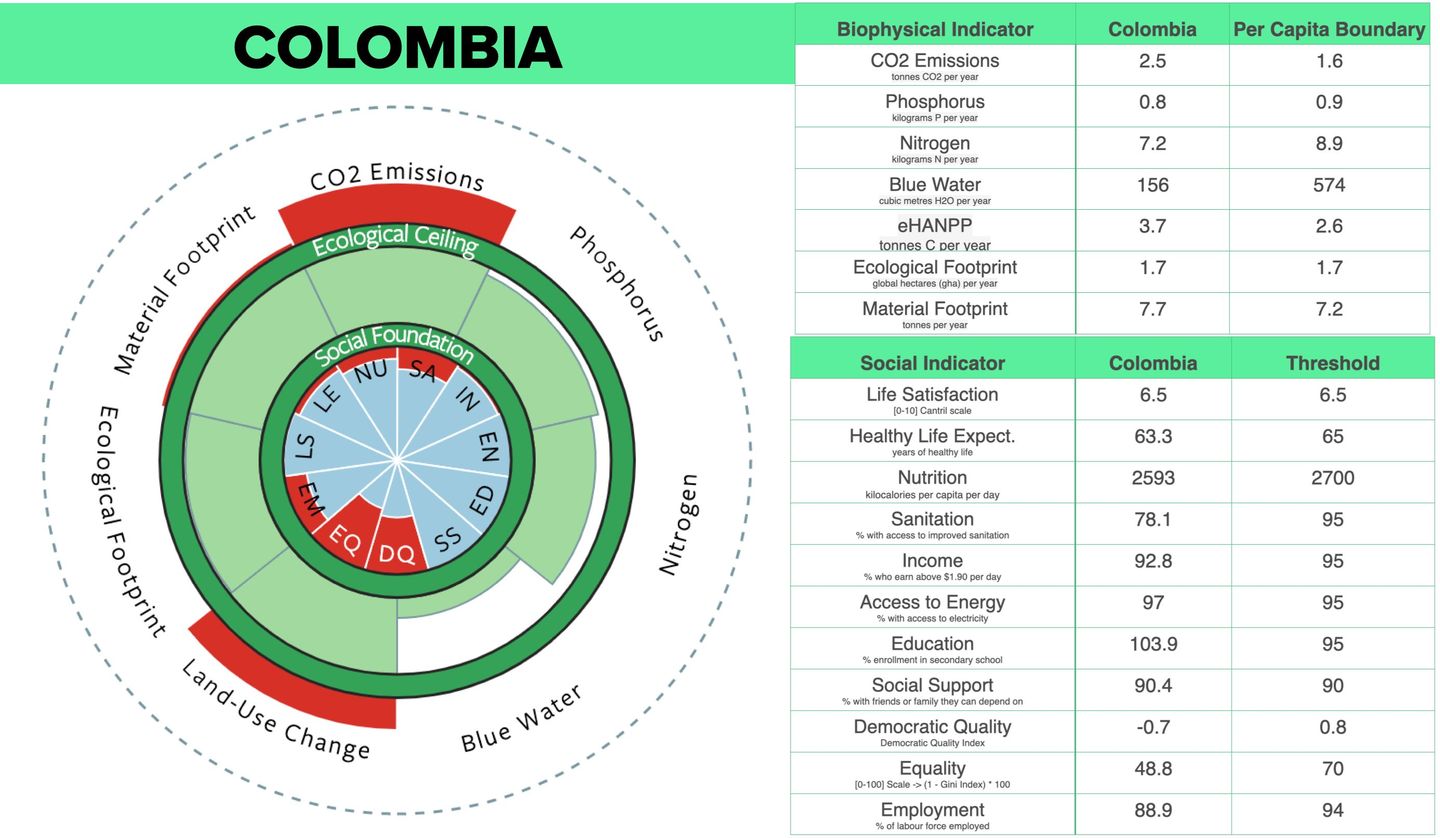

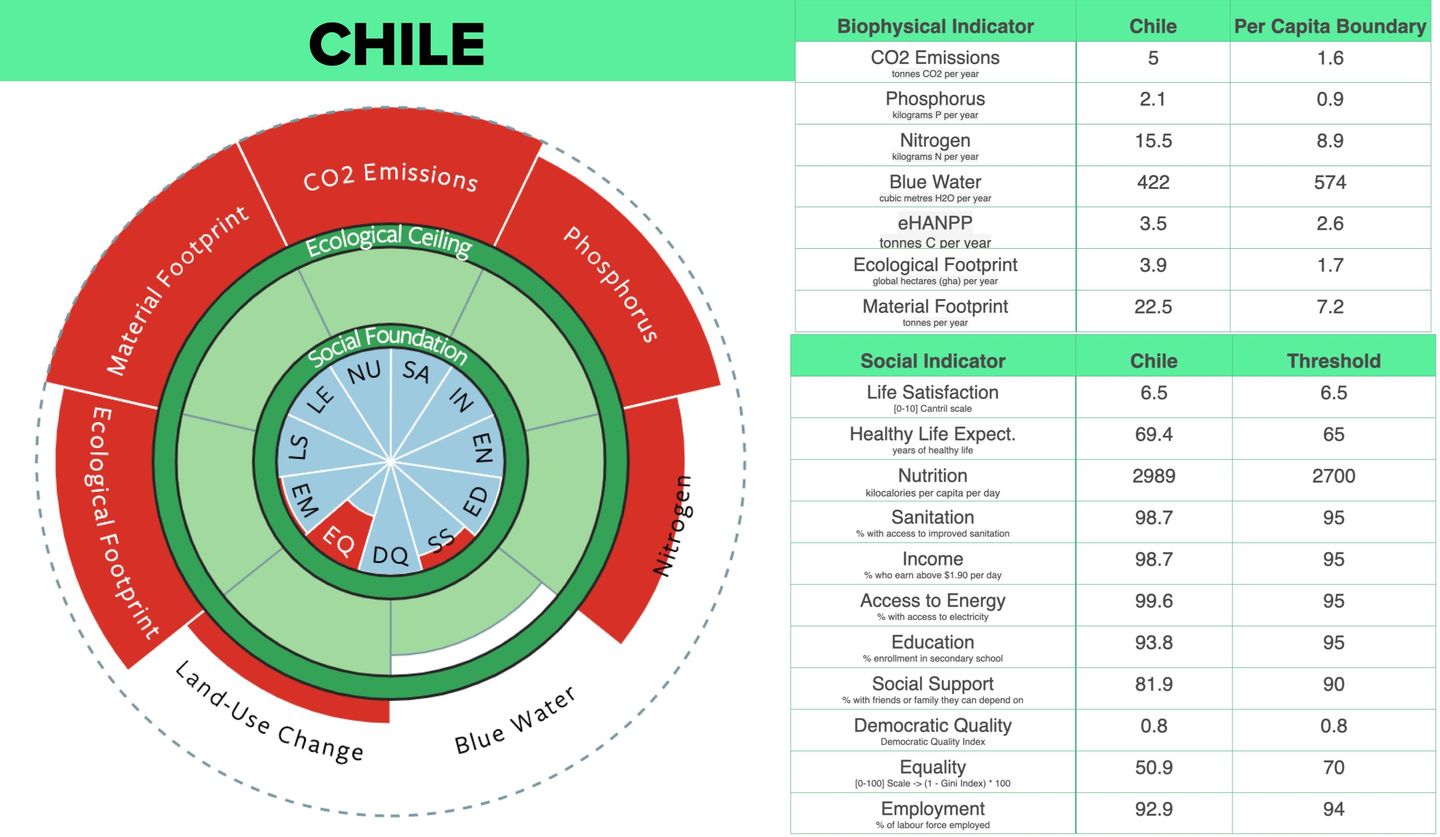

The planetary boundaries concept presents a set of nine frontiers needed to avoid large-scale or irreversible environmental changes to our planet. In 2022, we exceeded two boundaries*; environmental pollutants and freshwater**.

We will review some countries’ contributions to these boundaries and their performance on key human development metrics using the doughnut economics framework.

*14 scientists concluded in the scientific journal Environmental Science and Technology that humanity has exceeded a planetary boundary related to environmental pollutants and other “novel entities” including plastics.

C. Lorem Ipsum

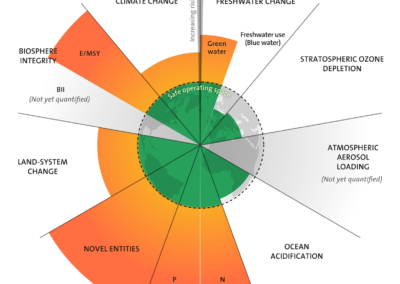

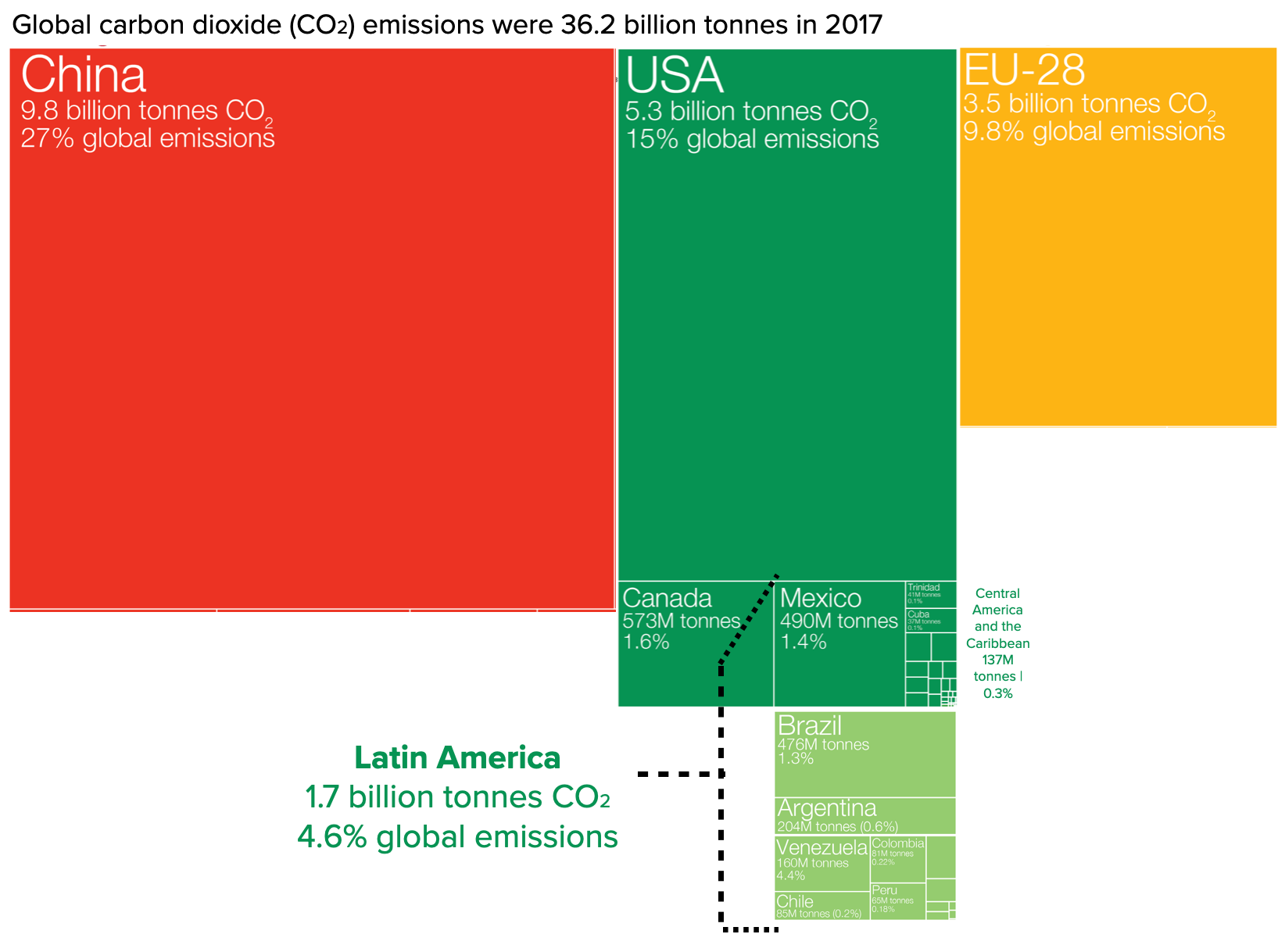

Climate justice The global north is responsible for 92% of the excess emissions that cause climate change. By contrast, most countries in the Global South are within their fair share limits.

D. Lorem Ipsum

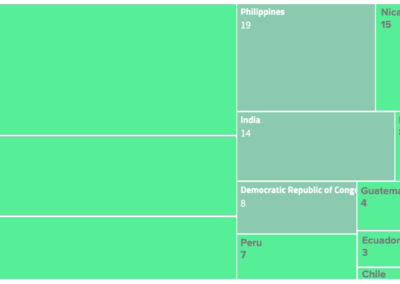

Indigenous people and environmental activists are at constant risk in the region, they are being harassed and killed at alarming rates.

75% of the 200 attacks against territory defenders recorded in 2021 took place in Latin America.

Sources: Lorem ipsum nuestro que estás en el cielo

Current Situation

Selected problems snapshot

Introduction

Argentina has long struggled to rein in fast-rising prices with inflation currently running at an annual rate near 80%. The government has pushed retailers to freeze some prices, with some supermarkets rationing purchases of staples like flour, sugar and milk but shopping costs have nonetheless soared.

Current Situation

Selected problems snapshot

Cities will be key to climate change

Urban Heat Island Effect: Cities tend to be warmer than surrounding rural areas, a phenomenon known as the urban heat island effect, due to factors such as increased energy consumption, lack of green spaces, and heat-absorbing materials. This can lead to increased energy demand for cooling, increased air pollution, and negative impacts on public health.

Transportation: Cities are often heavily reliant on transportation systems that rely on fossil fuels, which contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Encouraging the use of public transportation, cycling, and walking can help reduce emissions, but requires significant investment in infrastructure and cultural change.

Building Efficiency: Buildings are a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, both through energy consumption and through the production of construction materials. Improving the efficiency of buildings through retrofitting and building codes can help reduce emissions.

Water and Waste Management: Cities generate large amounts of waste and consume significant amounts of water. Improving waste management and water conservation practices can help reduce emissions and protect water resources.

Adaptation: Climate change is already impacting cities in many ways, including sea level rise, extreme weather events, and changing precipitation patterns. Cities must adapt to these impacts by building more resilient infrastructure, improving emergency preparedness, and managing risks associated with climate change.

Sources and references: Lorem ipsum que estás en los cielos

Planetary boundaries and human development

The doughnut framework* gained popularity with the book Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth. It is proposed as a compass for human prosperity in the 21st century, with the aim of meeting the needs of all people within the means of the living planet.

The Doughnut consists of two concentric rings: a social foundation, to ensure that no one is left falling short on life’s essentials, and an ecological ceiling, to ensure that humanity does not collectively overshoot the planetary boundaries that protect Earth’s life-supporting systems. Between these two sets of boundaries lies a doughnut-shaped space that is both ecologically safe and socially just: a space in which humanity can thrive.

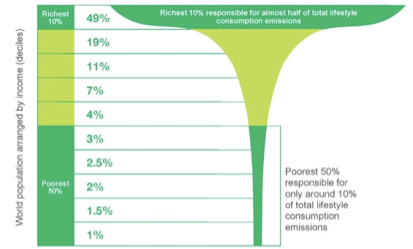

Climate justice: gaining perspective on emissions responsibility

The richest 1% was responsible for 15% of emissions between 1990 and 2015, that is, more than the entire population of the European Union and twice as much as the poorest half of humanity, which is only responsible for 7%*.

Sources and references:

*Oxfam Report: Extreme Carbon Inequality. Media briefing.

Sources: 2.X Adaptation from Our World in Data article Who emits the most CO2 today?. Website. 2.X Oxfam 2020 2.X World Inequality Database website.

2.X Global CO2 emissions by country: comparing China, USA, Europe and Latin America

2.X Percentage of CO2 emissions by income. World population.

2.X Historical CO2 emissions of the richest 10% in three countries v. Latin America

Silenced voices: defenders of the land and the environment

People defending the land and the environment fight peacefully in the frontline against climate change, the preservation of the world’s ecosystems, and the protection of human rights, but at the same time, they are facing terror campaigns on a daily basis that aim to silence their voices. Threats, bullying, judicial harassment, illegal surveillance, forced disappearances, blackmail, sexual assault, and murder are common practices.

The expansion of large-scale mining activities and agribusiness in Latin America has greatly increased territorial disputes and resulted in an alarming rise in violence suffered by activists, defenders of water, land, forests, and the rights of women, afro-descendants, indigenous people, and farming communities.

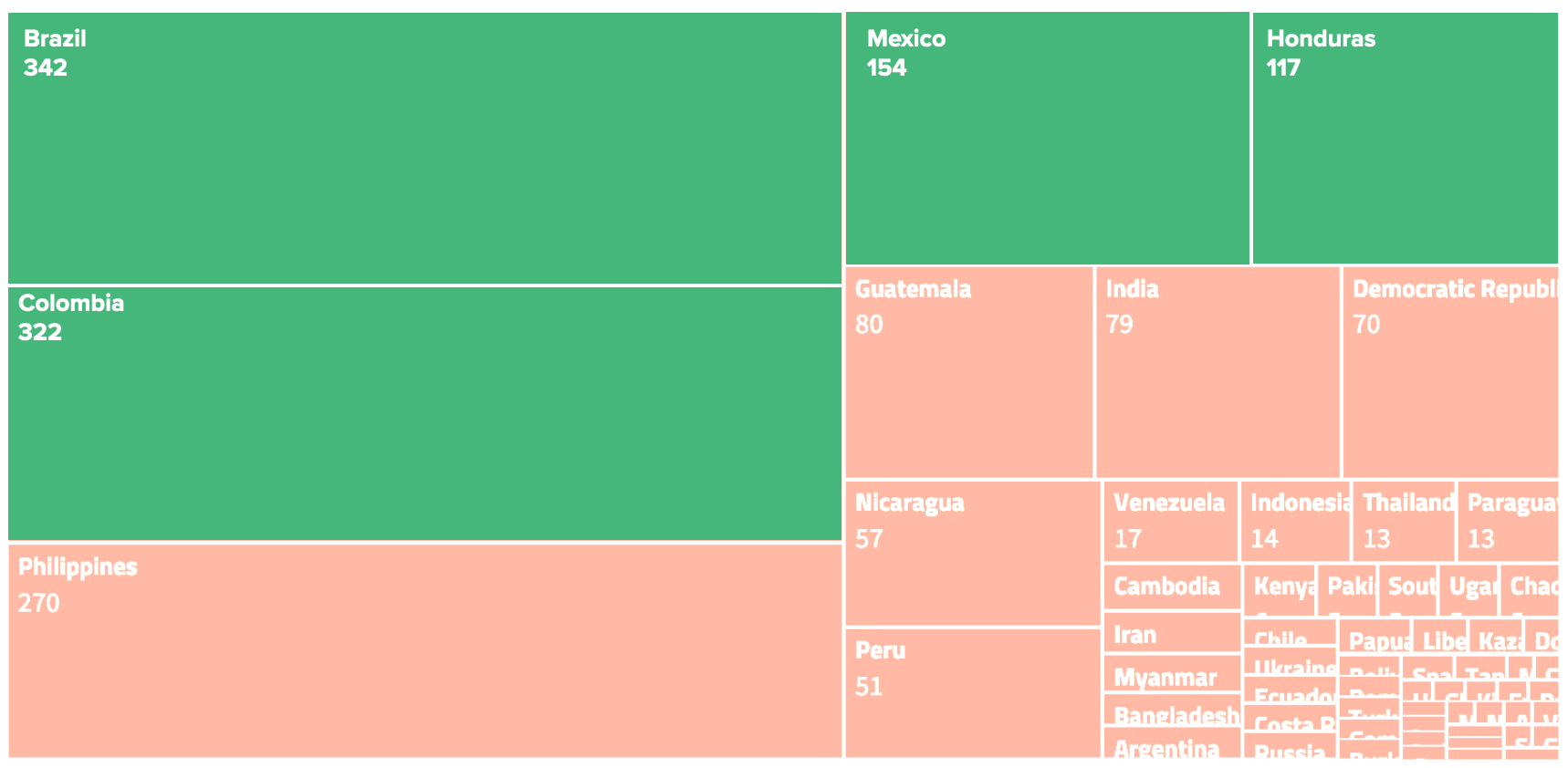

Brazil, 342.

Around a third of those killed were Indigenous or Afro-descendants, and over 85% of killings happened within the Brazilian Amazon.

Conflict over land and forest rights is the main driver of defender killings in Brazil, with the Amazon rainforest being the frontier of the struggle over Indigenous and environmental rights. Indigenous peoples have an important role to play as guardians of the Amazon forest, in preventing the emissions that come from deforestation and forest degradation, and in helping curb the climate crisis.

The failure of the state to defend land and environmental defenders even as it gives a green light to illegal resource extraction has led some to suggest that the government in Brazil has been captured by criminal interests.

Colombia, 322.

A sharp increase in legal and illegal agribusiness and mining business models pose a direct threat to the interest of the indigenous and afro Colombian communities living there because such large-scale economic activity carries a severe social and environmental impact on the native population.

2021 marked the fifth anniversary of the peace agreement, which put an end to over 50 years of conflict with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia. Land disputes are a driving force behind the killings of land and environmental defenders, and the agreement acknowledges the need to address matters such as forced land displacement, unequal land tenure and the substitution of illegal crops by alternative legal crops. However, to date the implementation of the peace agreement has fallen short: peace is still a distant prospect for many Colombians, and the consequences of ongoing violence are particularly felt by the most vulnerable groups, including small-scale farmers and Indigenous peoples.

Mexico, 154.

Conflicts over land and mining were each linked to two-thirds of lethal attacks. Around two-thirds of the killings were concentrated in the states of Oaxaca and Sonora, both of which have significant mining investments.

Forced disappearances are common, they are carried out by corrupt state officials and organized criminal groups, and send a chilling effect through families and communities.

Indigenous territories are highly vulnerable to the prolific number of large-scale extractive projects promoted by national and foreign companies and backed by the Mexican government. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has raised concerns about the lack of adequate consultation with potentially affected communities and the subsequent attacks on those standing against signature projects. The Commission has flagged criminalization and smear campaigns as harmful threats against land and environmental defenders in Mexico.

Honduras, 117.

“In Honduras, like in the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, women are on the frontline when it comes to fighting for our rights, against racial discrimination and to defend our environment and our survival. We don’t just fight with our own bodies; we also provide our strength, our ideas, and our proposals. We don’t just give birth to children, but also ideas and actions”, said Miriam Miranda, a Garifuna community leader defending the land belonging to Afro-Hondurans struggling against exploitation and plunder.

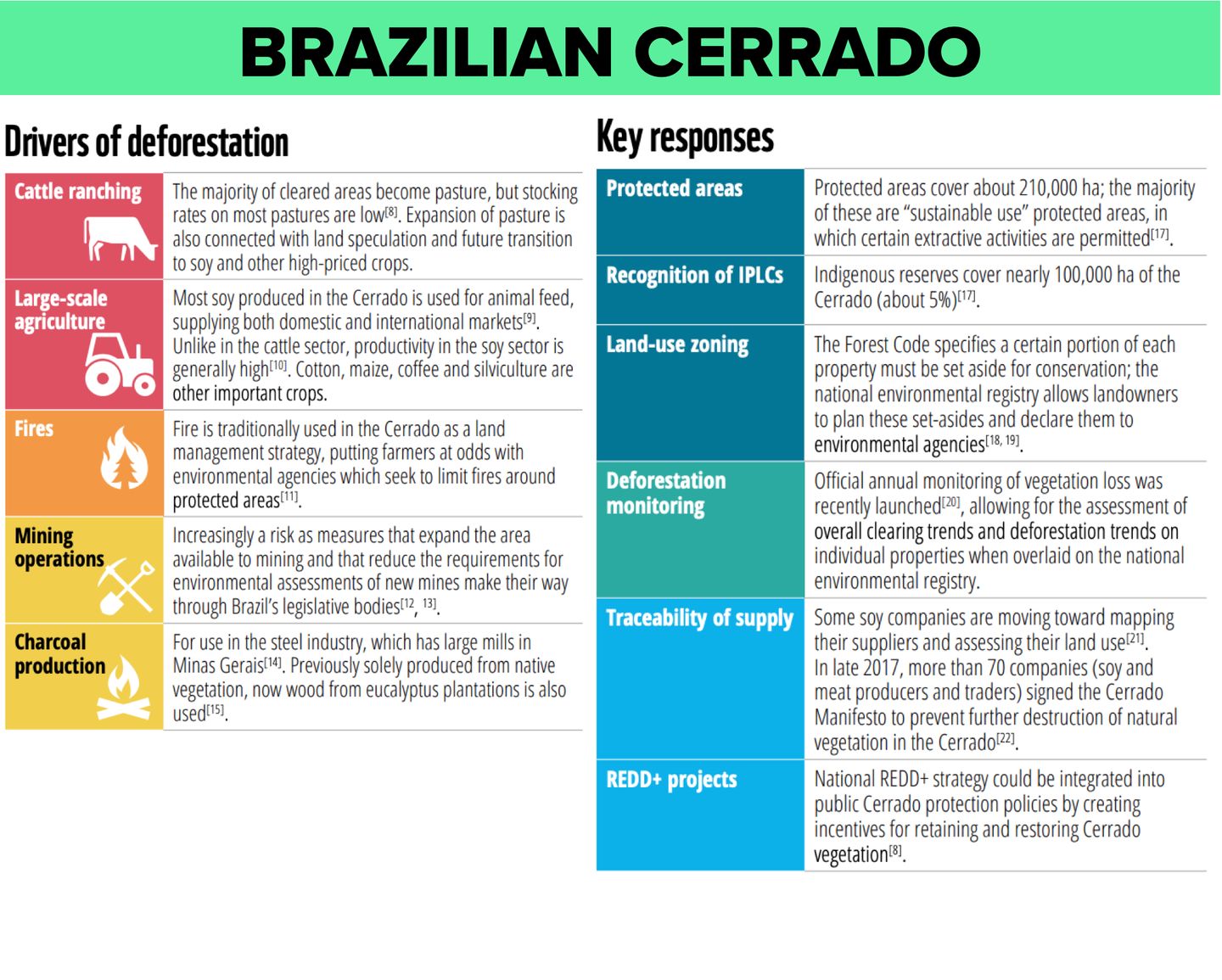

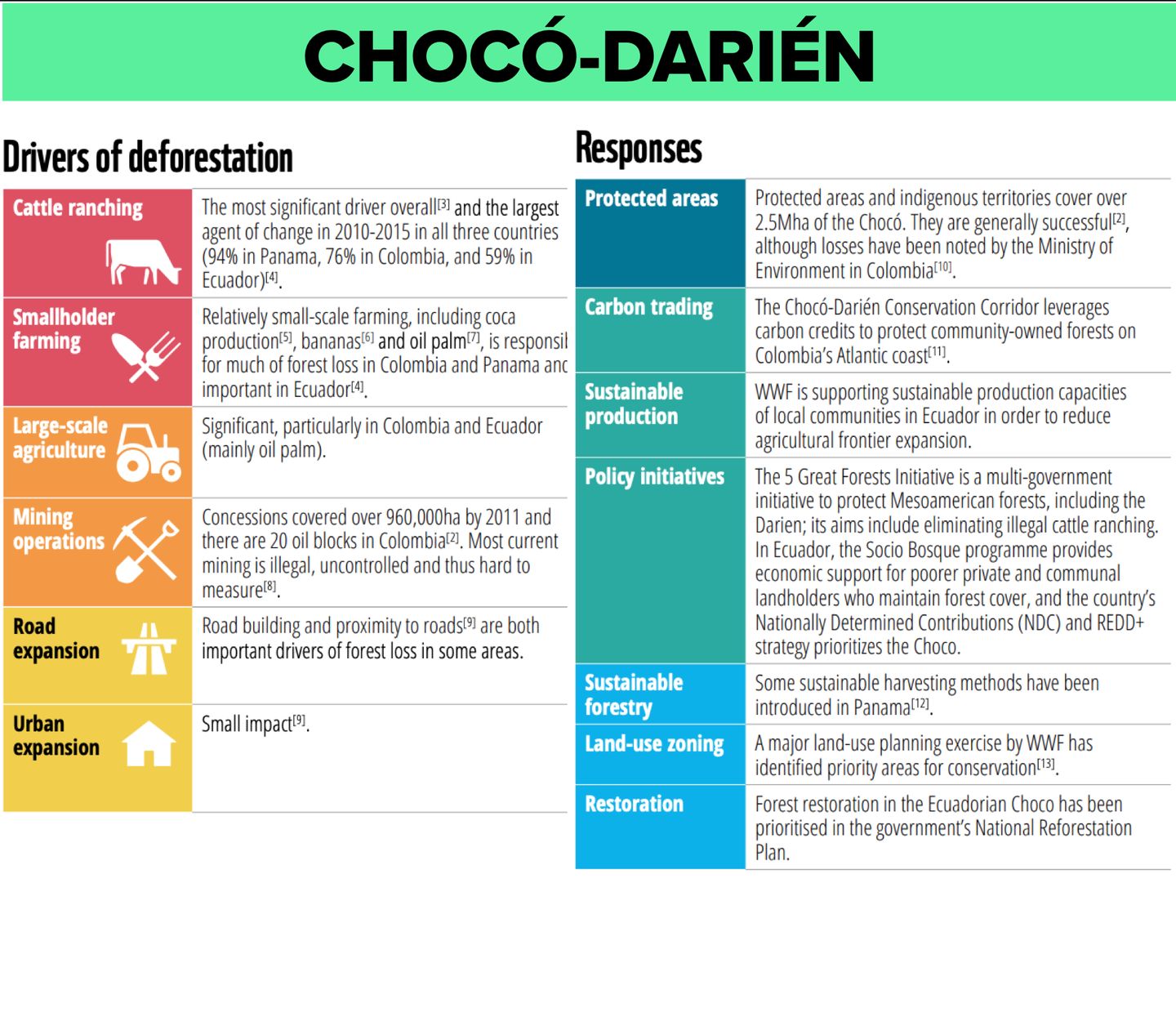

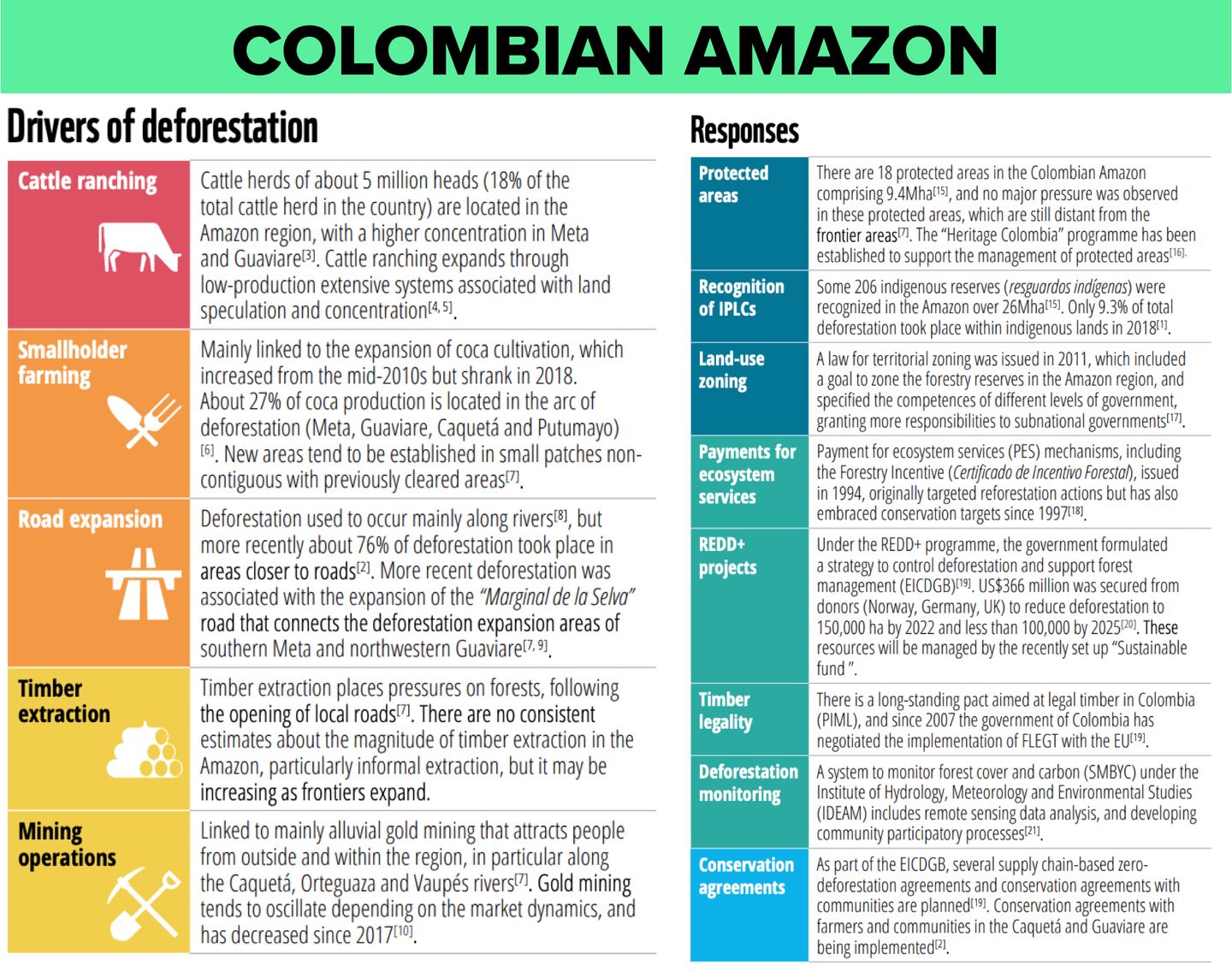

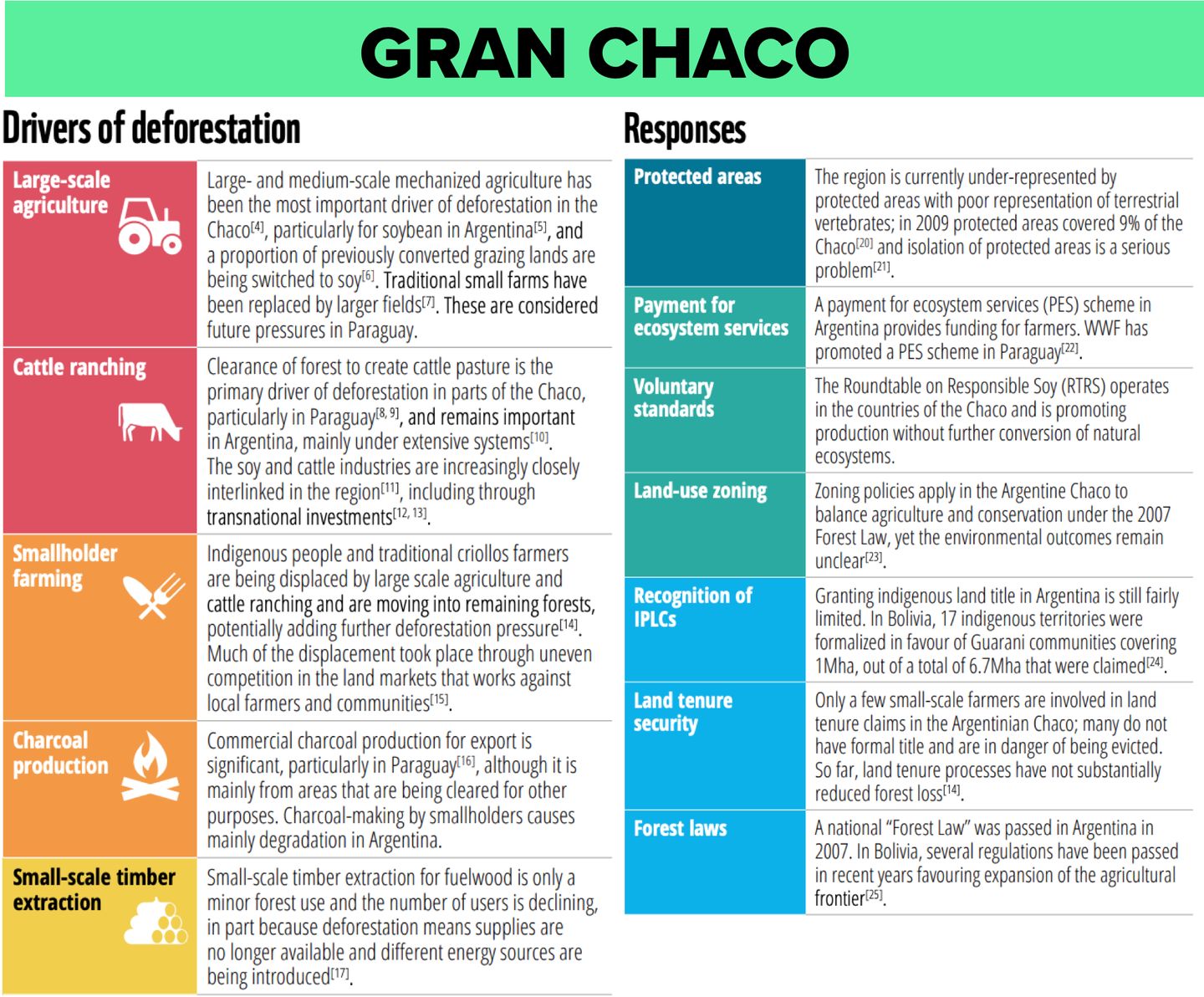

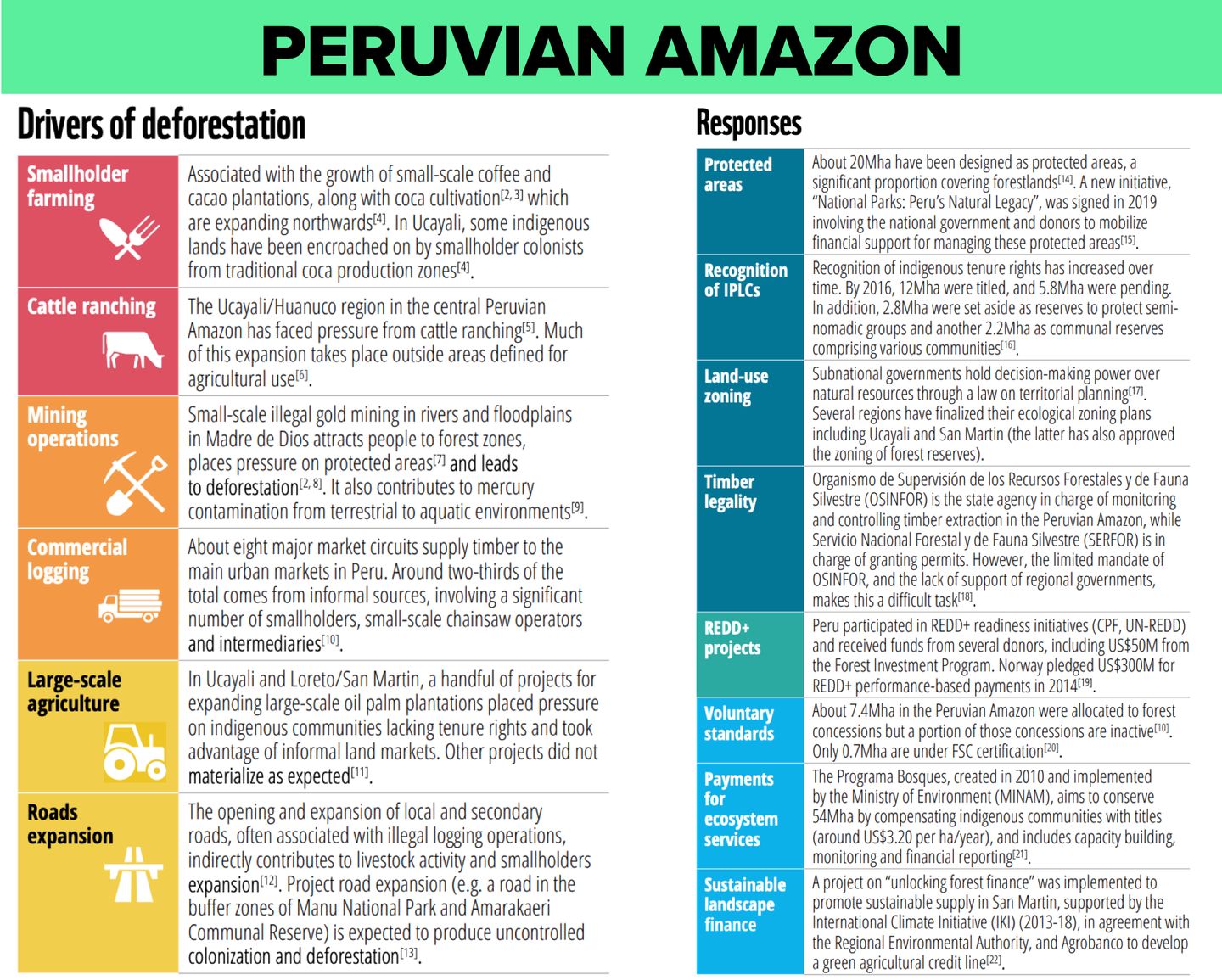

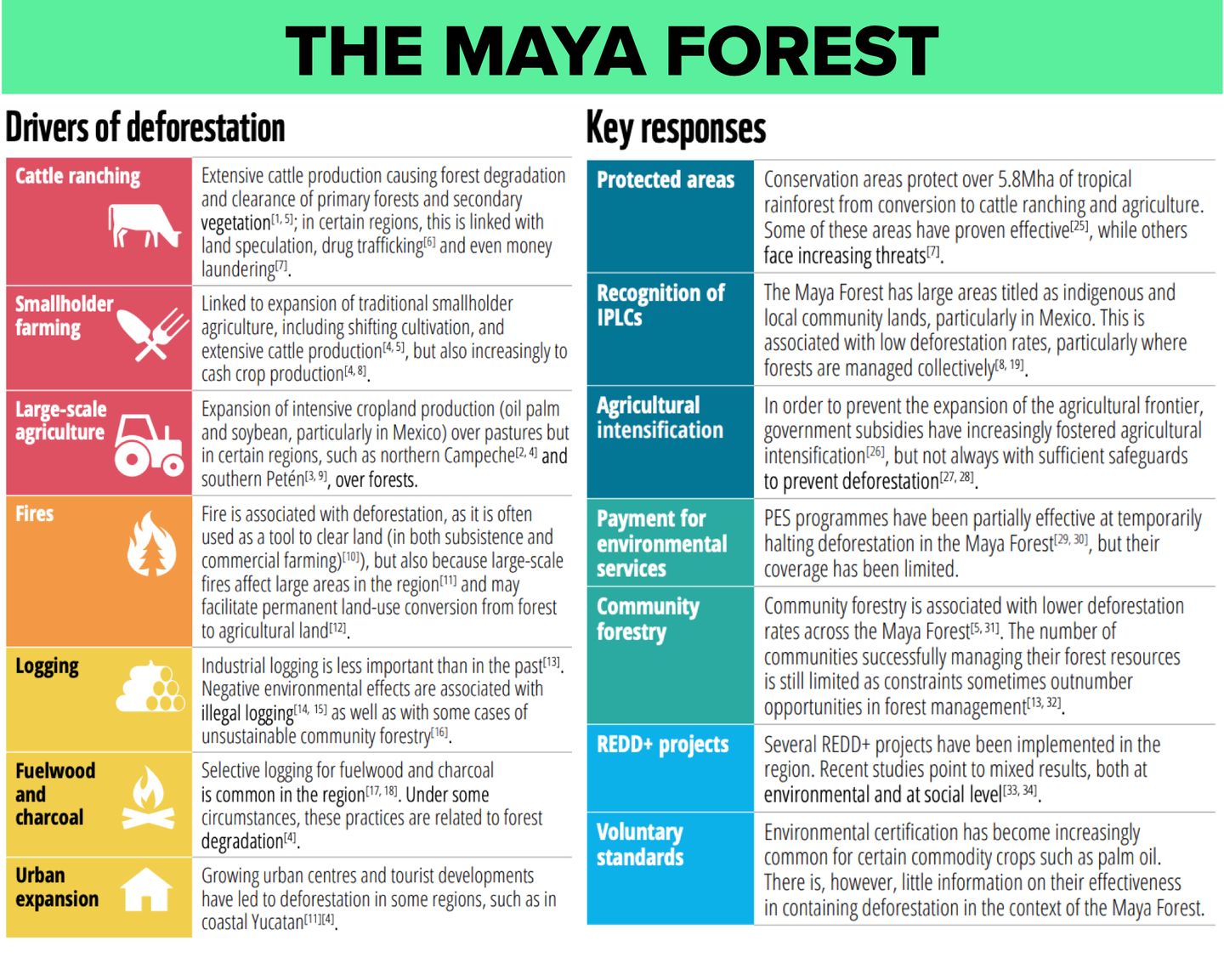

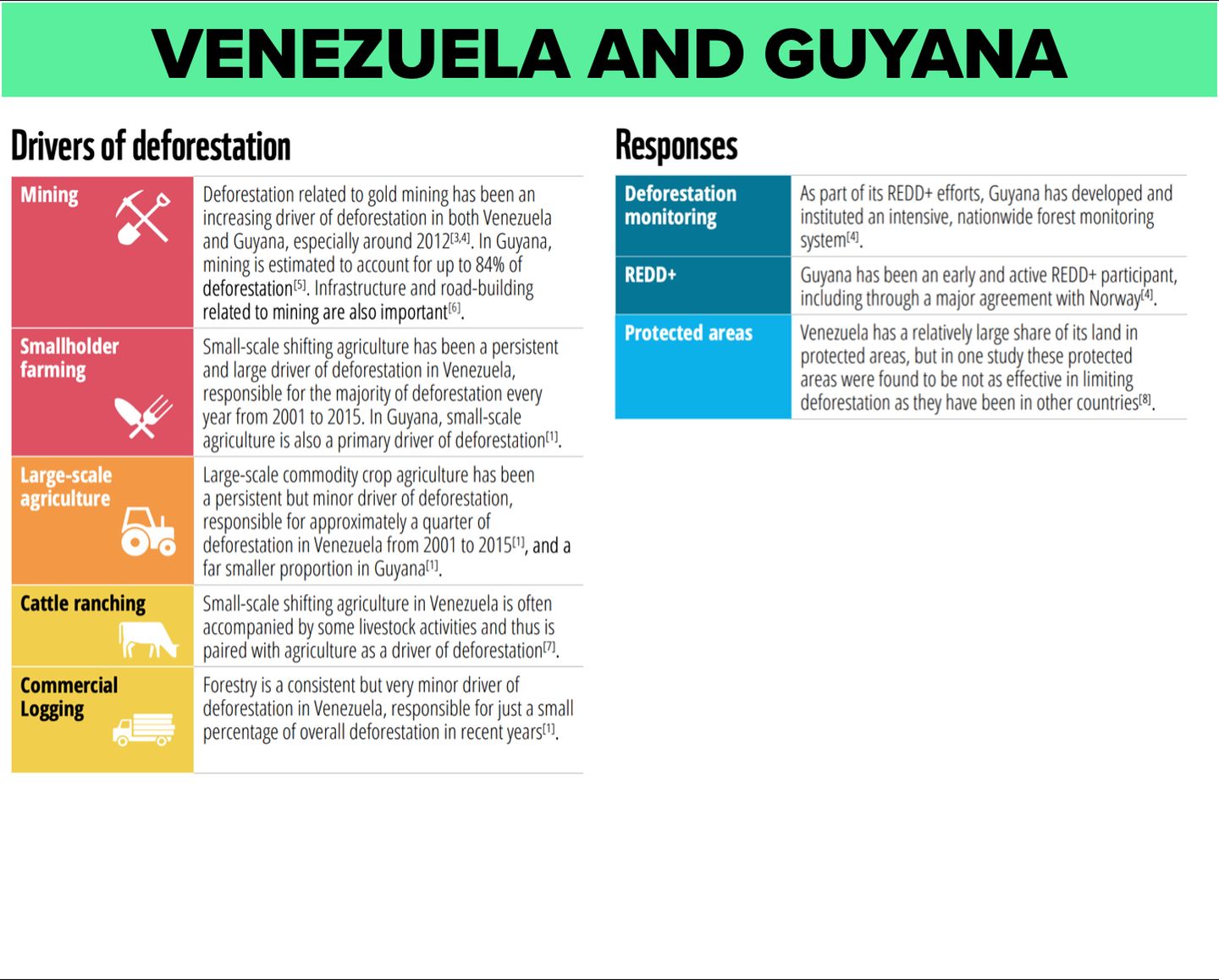

Deep dive: Deforestation drivers and responses

Introduction

Forests are home to more than half of the world’s land-based species, and globally, over 1 billion people live in and around forests and rely on it for food, shelter and livelihoods. After oceans, forests are the largest storehouses of carbon. But we’re losing forests at an alarming rate. Worldwide over 43 million hectares, an area roughly the size of Morocco, was lost in these ‘deforestation fronts’ between 2004 and 2017.

Industries that drive deforestation

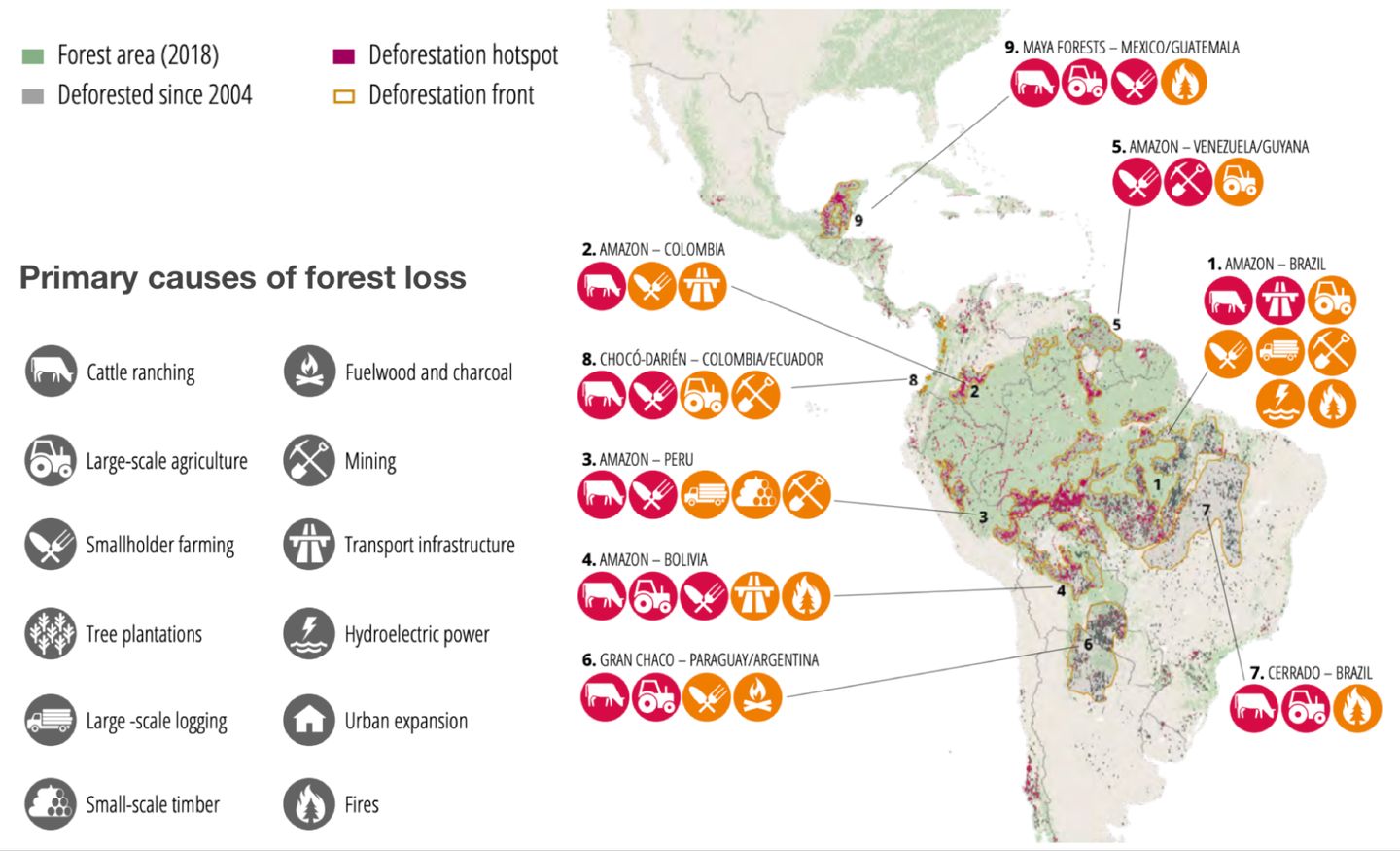

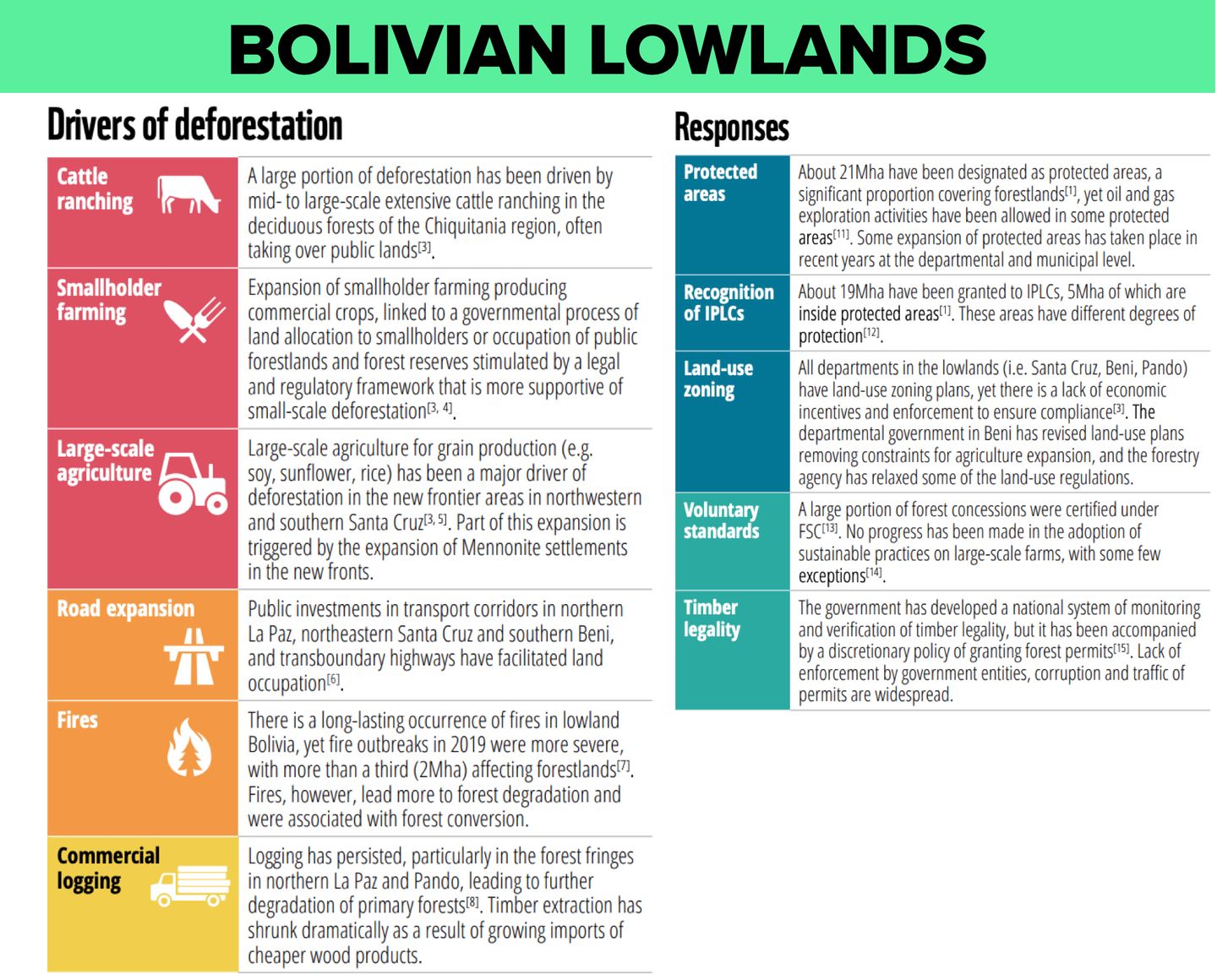

WWF identified 9 places in Latin America where deforestation significantly increased from 2004- 2017 in the region. The remaining forest is shown in green. The icons indicate the direct drivers for each of the fronts: primary causes of forest loss and/ or severe degradation are in red and secondary causes are denoted in orange.

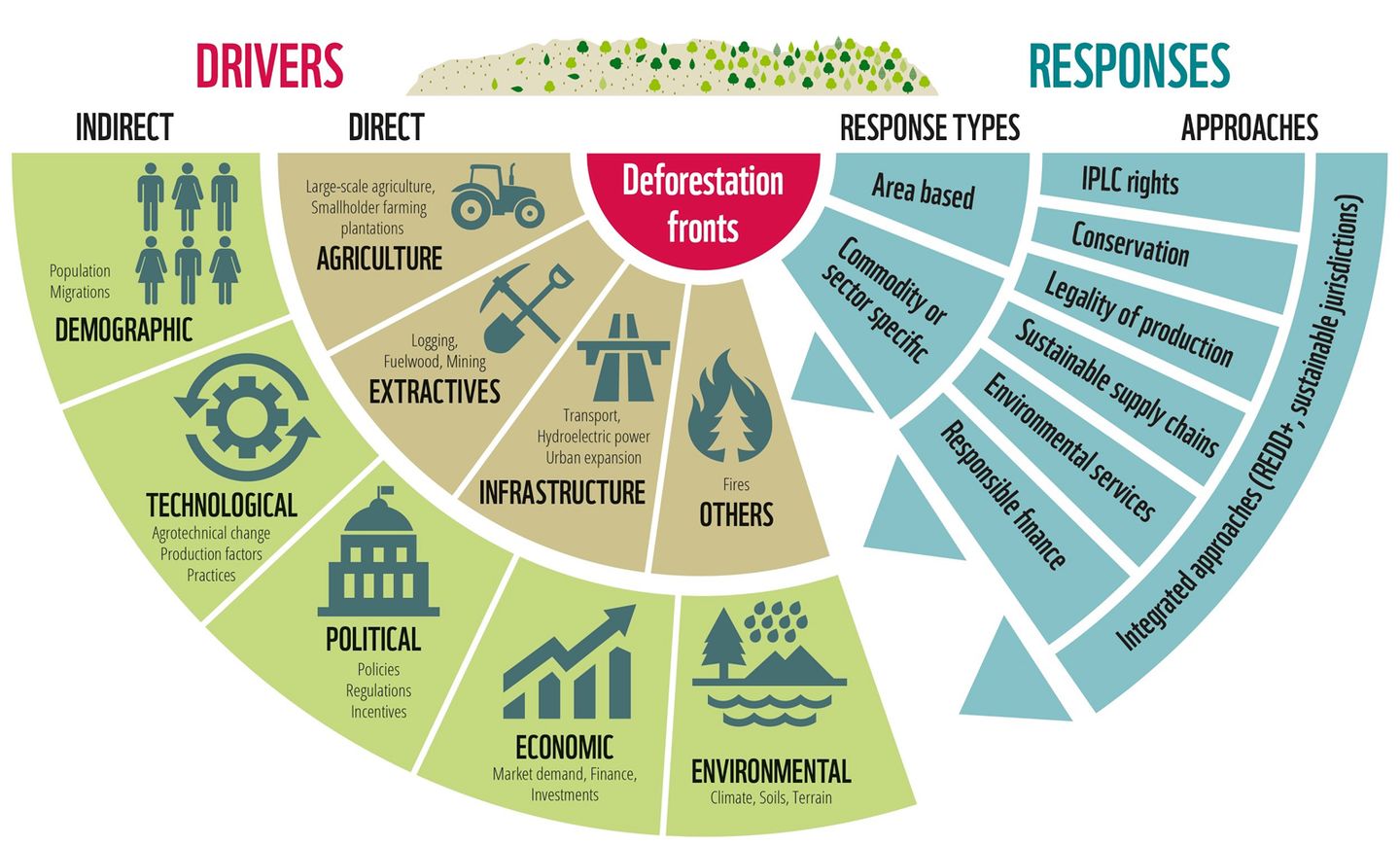

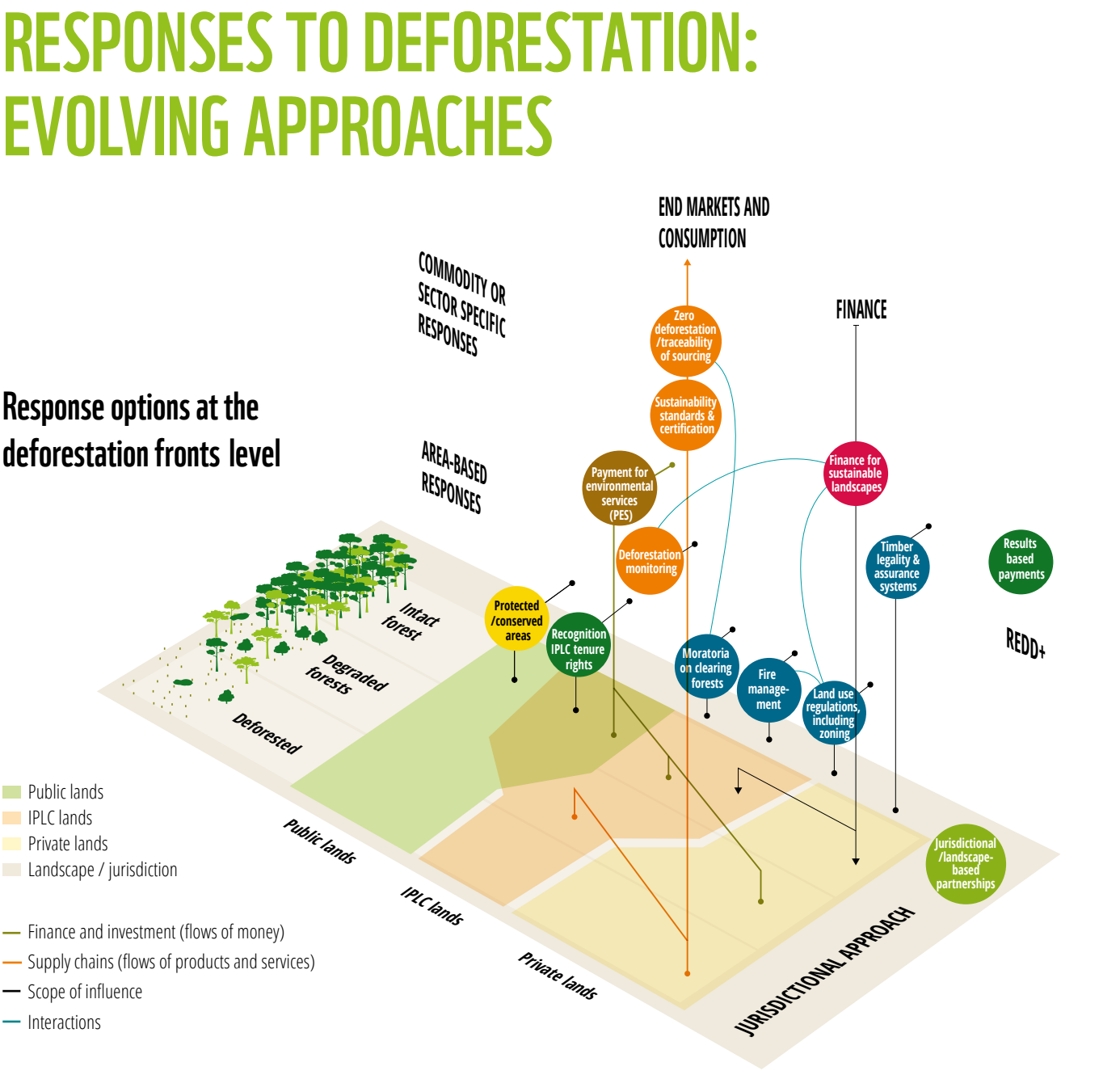

Approaches to halting deforestation have evolved over time. In particular, there has been a shift from relying solely on state policies and regulations to an increased emphasis on market-based initiatives, including PES and certification schemes. Corporate commitments to zero deforestation have also been increasing, including those of financial institutions.

Two approaches have emerged seeking to link multiple interventions the first is REDD+, the UN-backed scheme for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation- The second is jurisdictional and landscape approaches that are aimed at tackling deforestation along with achieving wider development objectives, often at subnational or landscape scales.

The above approaches embrace a different type of response is that for under two main groups:

- Area-based responses include the recognition of IPLC’s land tenure rights, governance of those lands and territories, and unsustainable economies within them. In addition, include other types of area-based strategies such as protected areas, moratoria, fire management, and land use regulations.

- Sector/commodity-specific responses include legality and assurance systems, voluntary sustainability standards and certification, zero-deforestation policies and traceability in sourcing, PES, financing for sustainable landscapes, and deforestation monitoring.

There is some overlap between these two groups of responses, since some area-based responses apply to a specific sector, while some sectoral responses focus on a particular area. Additional, yet more integrated responses include results-based payments and jurisdictional-based partnerships both of which tend to build upon or combine various types of responses circumscribed to specific territorial boundaries.

Sources and references: images and text on deforestation are taken from the report “Deforestation Fronts” by WWF.

Credit: Pacheco, P., Mo, K., Dudley, N., Shapiro, A., Aguilar-Amuchastegui, N., Ling, P.Y., Anderson, C. and Marx, A. 2021. Deforestation fronts: Drivers and responses in a changing world. WWF, Gland, Switzerland.

Deforestation hotspots

Change signals

Curated trends, signals or opportunities

Global corporate trend pushes regional offices to meet net-zero goals

More than one-third (34%) of the world’s largest companies are now committed to Net Zero, by cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible, with any remaining emissions re-absorbed from the atmosphere, by oceans and forests for instance. Their Latin American regional branches are seeking qualified talent, service providers and alternative solutions to meet their ambitious goals.

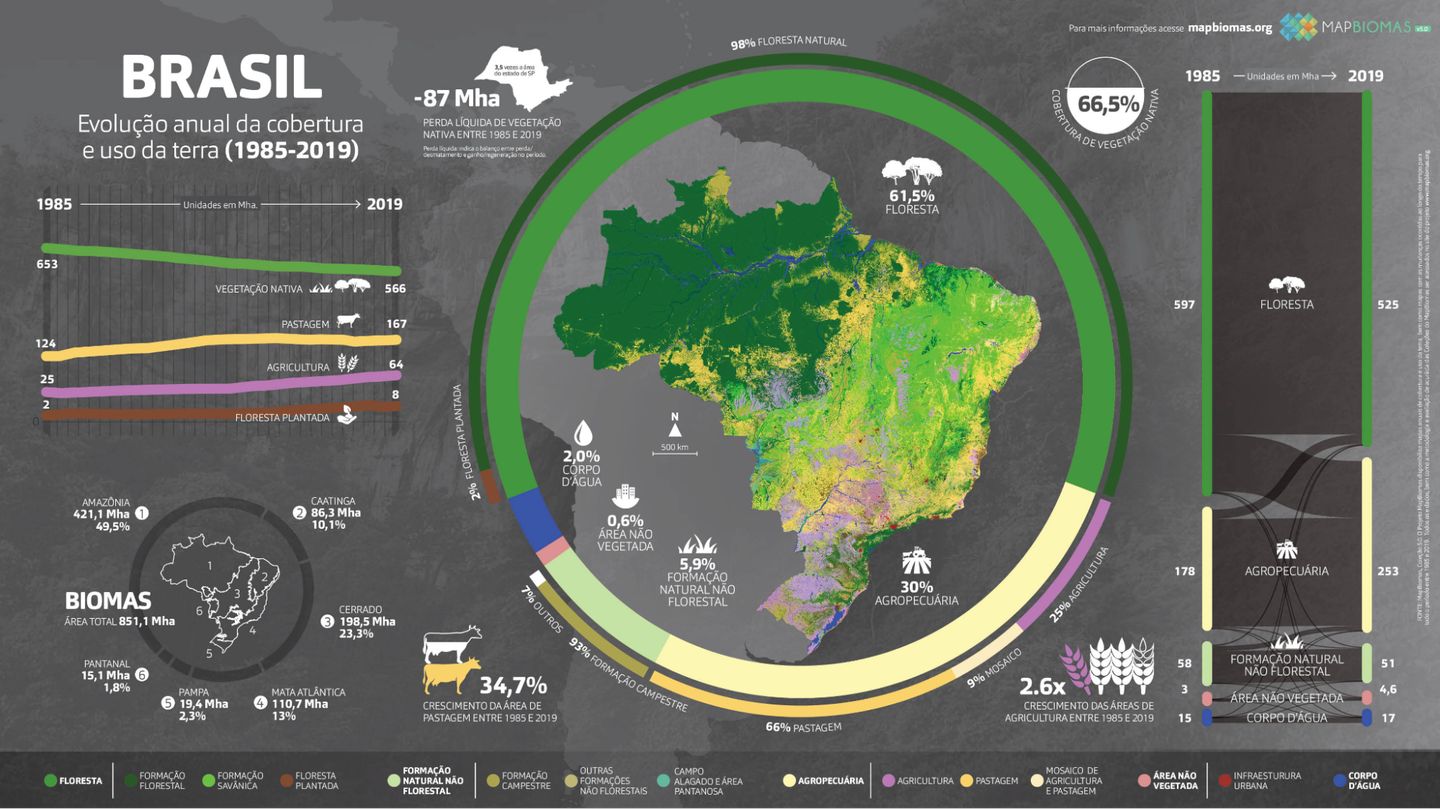

Land use independent monitoring

Brazil is the fifth largest emitter on the planet after China, USA, Russia, and India. While two thirds of emissions come from fossil fuels in the top four, two thirds of Brazilian emissions come from land use and land-use change.

MapBiomas combines remote sensing, computer science and local land use expertise with multiple global satellite images to create real-time insights. The initiative has produced 35 years’ worth of maps in less time and budget than it takes to create a single year of maps by traditional methods.

Source: Skoll Foundation: MapBiomas (2022). Foto ACV Brasil

Uruguay, a clean energy regional leader

After a severe, decade-long drought beginning in 1997, Uruguay found itself forced to import oil from its neighbor Argentina. In 2006 alone, Uruguay would end up importing nearly 75% of its energy needs. With that, the Uruguayan government began to invest heavily in homegrown renewable energy sources. Currently, the country generates over 98% of all electricity from renewable sources, primarily wind and hydropower.

Uruguay is also one of the most electrified countries in the hemisphere, with 99.9 percent of homes connected to the electric grid.

Source: Uruguay – Renewable Energy Equipment (2022). Renewable Energy in Uruguay Is Surpassing Expectations (2022). Foto Uruguay Government

Water harvesting and community governance

Isla Urbana is dedicated to designing and installing water catchment systems in Mexico, particularly where people lack water. Since 2009 they have installed more than 21 thousand systems that are equivalent to harvesting 871 million liters of water. Cántaro Azul focuses on providing technological and participatory solutions for access to safe water and sanitation in rural communities. We highlight, among its multiple approaches, the social franchise for access to drinking water and community water governance models.

Source: Isla Urbana 2022, Cántaro Azul 2022. Foto Cántaro Azul.

Cleaning water and producing food at the same time

More than one-third (34%) of the world’s largest companies are now committed to Net Zero, by cutting greenhouse gas emissions to as close to zero as possible, with any remaining emissions re-absorbed from the atmosphere, by oceans and forests for instance. Their Latin American regional branches are seeking qualified talent, service providers and alternative solutions to meet their ambitious goals.

Source: bioemprendiendo(2023) Foto: Instagram.com/microterra.mx

A regenerative network of meat producers

Manada coordinates a network of agroecological meat producers in Chile. The regenerative management that they promote with their producers implies that not only does it not require fossil energy (oil in machinery work, chemical fertilizers, agrochemicals, etc.) but it sequesters carbon and regenerates the soil. In addition, they focus on responsible production, paying fair prices to producers and including the community, including a cooperative that is part of its producers. Also the meat that is produced is free grazing and they do not use hormones or antibiotics.

Source: Carnes Manada (2023)

Change signals

Initiative spotlight

Rizoma Agro

A regenerative agricultural practice

Rizoma Agro is a Brazilian agroforestry company that focuses on sustainable production of timber, fruits, and other crops. Founded in 2010, Rizoma Agro has become a leading voice in the movement towards sustainable agriculture and forestry practices in Brazil. The company operates in the Brazilian Amazon region and aims to promote reforestation, agroforestry, and the conservation of native forests. Rizoma Agro’s main product is Brazilian teak, a high-value hardwood used in the production of furniture, flooring, and other wood products. However, the company also produces a variety of other crops, including cocoa, açaí, and cupuaçu.

A regenerative agricultural practice

Agroforestry is a land management system that integrates trees with crops and/or livestock, creating a more sustainable and diverse agricultural system. Agroforestry systems can provide a range of environmental and economic benefits, including soil conservation, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and increased food security. In agroforestry systems, trees and crops are planted together, allowing for complementary interactions between different species. For example, trees can provide shade for crops, protect soil from erosion, and improve soil fertility by fixing nitrogen. In turn, crops can provide additional income streams for farmers and help to maintain the health of the agroforestry system.

Agroforestry is important to address global warming because it can help sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Trees are a natural carbon sink, meaning they absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and store it in their biomass and in the soil. By combining trees and crops or animals, agroforestry systems can increase carbon sequestration potential while also providing multiple benefits to farmers and the environment. Additionally, agroforestry can reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, which are often energy-intensive and contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Scale of agroforestry in Brazil and its challenges

Despite the potential benefits of agroforestry, its scale in Brazil is still relatively small. Compared to the 263 million hectares under farming systems (2020), which represents approximately 30% of the national territory, agroforestry in Brazil covers around 5% of the farmed land, and there is no information if these agroforests follow the conventional model or are oriented by agroecological principles.

Despite the benefits of agroforestry, the expansion of agroforestry systems in Brazil and Latin America faces several challenges. The main barriers to the adoption of agroforestry at scale in Brazil includes the lack of technical assistance, limited access to finance, regulatory barriers, land tenure issues, and limited market access. Many farmers lack the technical knowledge and support needed to establish and maintain agroforestry systems, while financing options for such projects are often limited. The legal framework for agroforestry in Brazil is complex and can be a barrier to adoption, while land tenure issues and limited market access can make it difficult for farmers to invest in agroforestry systems or find buyers for their products. Additionally, the high upfront costs of establishing agroforestry systems can be a barrier for smallholder farmers, who may lack the resources to invest in long-term land management practices.

Sources: World Agroforestry, 2023. How agroforestry can restore degraded lands and provide income in the Amazon, Mongabay 2023. Schuler, H.R.; Alarcon, G.G.; Joner, F.; dos Santos, K.L.; Siminski, A.; Siddique, I. Ecosystem Services from Ecological Agroforestry in Brazil: A Systematic Map of Scientific Evidence. Land 2022, 11, 83. Farming Destroyed Brazil’s Rain Forests. It Could Also Save Them, Time 2023. Fotos: Ellen McArthur Foundation, 2023 and Mongabay 2023.

2022 REPORT